Ah-ooo! Barenboims of London

A Special Guest Review of the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra at Royal Festival Hall

My first time seeing Daniel Barenboim was nearly two decades ago at a dress rehearsal of the Vienna Philharmonic. The piece was Beethoven’s Third Symphony (“Eroica”), and watching it rehearsed was a master class in conducting. Maestro Barenboim, who spoke to the orchestra in fluent German, was able to coax the greatest subtleties in unified musical gesture from a piece which was so frequently performed and well-known as to court overfamiliarity. Yet these two giants — conductor and orchestra — could nimbly dance together, achieving new heights through even the most familiar of musical fare.

Maestro Barenboim’s strength in relationships yielded, around the same time, a very special ensemble — an orchestra which he hoped would model a greater dialogue and co-existence. The West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, founded in 1999, was comprised of Israelis, Palestinians, and Arabs and purposed itself to fight ignorance and encourage mutual understanding while united around the shared project of producing great classical music.

Barenboim started this venture with the famed author and Columbia professor, Edward Said. While largely critical of Western culture and one of the foundational teachers of post-colonial theory, Said was also an accomplished pianist who largely preferred Western classical music to the Arabic music of his Palestinian community. Launching the orchestra with Daniel Barenboim, the two hoped to create a sonic foundation for a future peace.

With a review of the orchestra’s recent Romantic-era rendezvous at Royal Festival Hall, which featured Mendelssohn's Italian Symphony and Brahms' Fourth Symphony, it is my pleasure to introduce my Substack colleague,

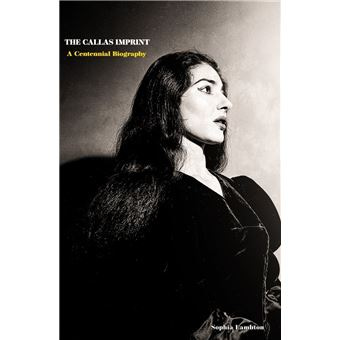

.Sophia is a writer of singular intensity. The author of a seven-part literary saga, The Crooked Little Pieces, she also recently published the authoritative biography of the great Greek soprano, Maria Callas, based on twelve years of fever-pitch research from myriads of interviews, archives, and never-before seen correspondence. A resident of London, Sophia also is a well-published music critic, and today generously offers her take on the musical merits of the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra following last week’s performance at Royal Festival Hall.

Please enjoy her review below, as well as her signature coloratura-style prose.

Rigid Rage Inhibits the Romantics: Daniel Barenboim and West-Eastern Divan Orchestra Resteer Brahms and Mendelssohn at Royal Festival Hall

by Sophia Lambton

At the propulsive engine of a heavy-handed driver the composers missed their winding lanes of daydreams.

Loose from overspilling souls, Romantic symphonies disguise the cracks from their creators’ wear and tear with perfect lacquer. Tackling them performatively is an act of deconstruction in the virtue of recomposition. Isolated from its peers, each section practices, succumbs to the conductor’s tempo; sculpts a flair. Its flawful episodes en route to showtime linger in inelegance like the composer’s misting tinges of imagination: flapping, scratching, crackling to get out. They clamor for release until their maker deems the fragment eligible.

Art borne of nature trundles to its roots, regenerates and serves a newer magic.

Escorting Mendelssohn through the museums of Rome and Naples, conductor Daniel Barenboim handed West-Eastern Divan Orchestra the challenge of the master’s Fourth Italian Symphony at Royal Festival Hall last Monday, 4 November. Splendor impressed strings with iridescent sunrays: flooding accents of fortissimo in hard and fast idyllic sprays. At the expense of woodwinds’ dainty jaunts the violins insisted on repeat crescendo in a dazzling hedonism. Mostly lacking in vibrato, they displayed hegemony in efforts that eclipsed the other sections’ zest.

Second movement “Andante con moto” followed with an overcautious tempo. Straitlaced militancy harnessed lower strings in a strict treatment of these bars depicting Catholics’ pious marches through the streets: at one point notes in trills were played pristinely equidistant. Restraint dulled down the animation in a rendering that shuffled rising-falling arcs of lower strings discreetly out of earshot.

More modestly, “Con moto moderato” offered deferent diminuendi – highlighting the flute duo and horns yet failing to cohere them in an interplay. At Barenboim’s direction woodwind instruments slid stealthily into a muffled pianissimo: the victims of their own tranquility.

Adroitly striking strings announced the “Saltarello: Presto” final movement with uncalled-for menace, oftentimes abstaining from staccati miming native dances. In a boycott of rubato they unveiled a tense stampede while pizzicato on the double bass seemed humble. Shunning jubilance, the curated interpretation seemed a contest stifling some collaborators whilst indulging others. Claps of castanets appeared to seethe in fierce strings’ unabating thunder. The percussionist rushed to suppress his timpani drums’ resonance with an arresting hand. Viciously enlivened, Barenboim’s ensemble emerged too homogenous to mirror the Italian landscape.

Luscious rue imbues Brahms’ fourth and final symphony: meanders through the ethers of illusion and the trenches of despair. At constant odds, his sections restlessly embroil each other in unflinching conflicts – pitting cynicism against hope; believers against sceptics. At Barenboim’s baton the opening movement staggered its serenely climbing chords; delaying them to break their berceuse. Mellifluousness was amiss in samples showcasing the pauses between chords more than the notes themselves. Dormant double bass notes ran too soft a course and woodwind stalled behind. In sluggish rigidness the cellos whiled away their ripening arpeggios.

Flimsy slimness characterized oboes’ timbre as they spelt out ditties in “Andante moderato”: here a self-defeating foray into musical one-upmanship. Disparate tempi overtook the strings; eventually their tremolos were far removed from one another. Intensely pressing bows struck cuttingly into third movement “Allegro giocoso,” whose pedantic efforts at dynamic peaks grew overwhelming. One instrument began occasionally to emit a buzz resembling the vibration of a loosened string.

Crackling like a throat racked by catarrh, the orchestra’s division of trombones dispersed in contrary directions in the final “Allegro energico e passionato” movement. A solo flautist oozed despondency in her motif but strings’ fortissimo held sway soon after amid puddling horns. Unstitched was this terrific test of a climactic symphony in a performance focused solely on its furor.

Fate was delayed in this exhibit of unfettered engines prone to overheat – a feat that drove home the Romantic masters’ self-destructiveness but left behind their art.

Resident in London, Sophia Lambton is an English-Russian-Jewish writer who has been a professional classical music critic since the age of seventeen. Beginning her career at Britain’s oldest classical music magazine, Musical Opinion, she has contributed to The Guardian, Bachtrack, MusicOMH, BroadwayWorld, BBC Music Magazine and Operawire.

Sophia writes regularly on Substack at Crepuscular Musings | Love of Classical Music and Other Arts