Some people say I look Jewish.

It could be the Ashkenazi profile or the beard, or my penchant for Irish hats that fit in as easily in Brooklyn as in Anatevka. Or all three.

Beyond the Music is a reader-supported guide to Jewish music. If you like what you read, please consider taking out a paid subscription.

Nowadays “look Jewish” is beautifully more complicated, as the world is filled with Jews of many colors and ethnic backgrounds. Yet among those I admit that I have the Ashkenazi look, and am often mistaken for any number of Tevyaesque men who attended this or that summer camp or conference, but who are not, in fact, me.

Yet rarer still do I have the privilege of meeting a professional doppleganger —not in looks so much as in interests. And I’m happy to introduce him to you today as a guest author at Beyond the Music on the subject of Argentinian cantors.

Cantor

is the Director of Beit Asaf, the cantorial school of the Seminario Rabínico Latinoamericano in Buenos Aires, Argentina. A creative and wide-ranging thinker, he is now pursuing both rabbinical studies at the Seminario and a PhD in Jewish Studies at the Ashkenazium in Budapest. His Substack newsletter, Nebujim, is a great Spanish-language meditation on modern Judaism and the weekly Torah portion.It is no small wonder that Cantor Kohan and I are both doctoral students, cantorial educators, and Substack writers who work part time for the same synagogue (We’re also both Ashkenazi men with beards, but as I mentioned, that’s easier to find). But it is even more thrilling to have him writing today on the subject of Argentinian hazzanut and its unique origins — down on the farm.

The History of Argentinian Hazzanut

by

If I say Argentina and you’re a religious person, you’ll think of Pope Francis. If you’re a sports fan, you’ll think of Lionel Messi. And if you’re a foodie, you’ll probably think of good wine and great meat. But…What if I tell you to also consider Argentina as a fascinating place for Hazzanut lovers? Even more…What if I tell you in case you’re a Hazzanut lover you must know about Argentinian Cantorial history?

Historically, Argentina has the largest Jewish community in Latin America, and for decades had one of the largest in the world. More importantly, it has also been Latin America’s main “exporter” of Jewish clergy, not only to the region but also to North America and Israel. Until recently, Buenos Aires had the only Spanish-speaking, non-orthodox rabbinical school in the world (nowadays there’s also a Reform rabbinical school in the same city). Even today its Cantorial Institute, which I have been granted the kavod (honor) to lead since 2020, is the only one in the region.

Unlike the US and Canada, Argentinian hazzanut wasn’t born in the big cities and their ornate synagogues, nor even modest urban shtibls or medium-sized shuls, but in the countryside. As wild as it may sound, Argentinian cantorial art grew next to corn and cattle fields.

Almost six million immigrants entered Argentina between 1882 and 1950, the majority of them Italians and Spaniards. Together with them also arrived other minorities such as Welsh, Armenians, Slavs, and of course Jews, most of them fleeing from Czarist persecution. This is why Argentinian slang for Jews is ruso — “Russian,” — since most of the Jewish migrants had Russian passport.

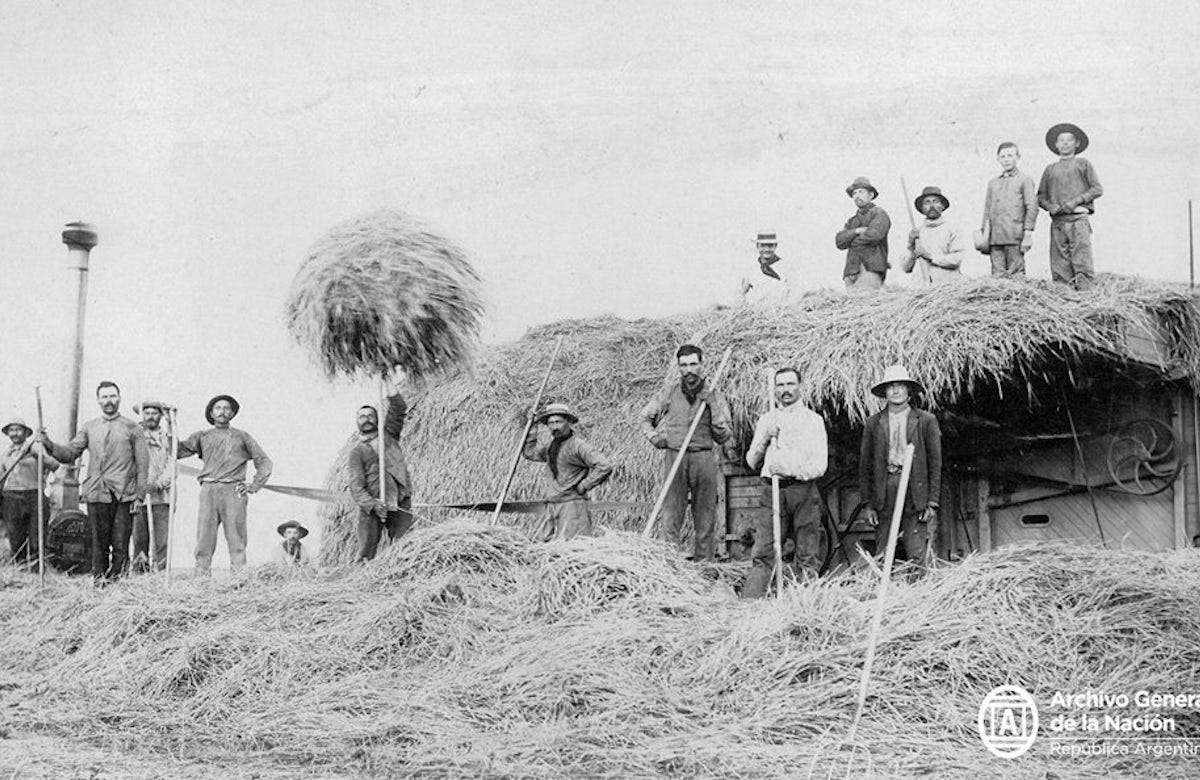

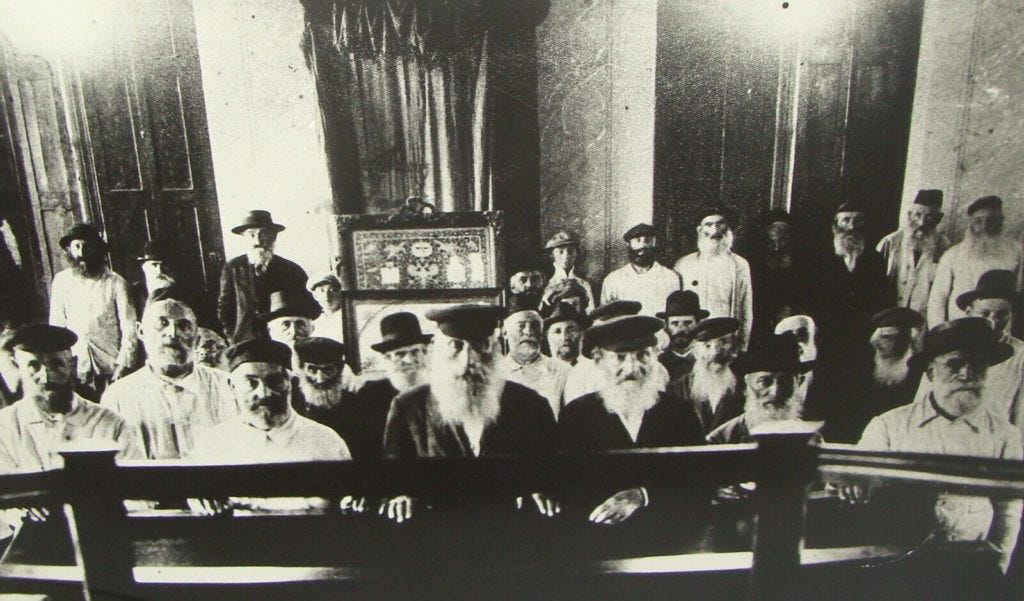

From the times of the Spanish conquest of South America, Sephardic crypto-jews (the conversos or marranos) arrived to the region trying to escape the Inquisition. But the first massive wave of Jewish immigration to Argentina started in 1889, when the ship “Wasser” arrived to the country. At that time, there was huge and almost empty territory in Argentina, and the local government permitted the acquisition of agricultural lands (mostly in the center of the country but also in the north) by the Jewish Colonization Association, led by Baron Maurice de Hirsch of England. Thousands of Eastern European Jews were settled in no less than seventeen colonies in several provinces, the two most important being Mosesville (in the Province of Santa Fe), and Rivera (in the Province of Buenos Aires, where my great-great-uncle was a cantor).

Following the kehilla model of Eastern Europe, each colony had one or several synagogues, a cheider (religious school) and a cemetery. Though not every colony had a Rabbi, all of them had a schoichet (ritual slaughterer), a mohel, a teacher and of course… a cantor. But unlike in New York, Chicago, or even Buenos Aires, the colonies were too small for cantors to make a living only by davening or singing. Most of these early Argentinian cantors were artisans, businessmen or even farmers. Who knows, maybe they even practiced their Kol Nidrei or Hineni while fixing shoes or harvesting wheat.

For technical and financial reasons, there are virtually no recordings of these first generations of local hazzanim. We know about them mostly through pictures and oral testimonies, and even probably everyone thought their local hazzan was the best, we can fairly assume their singing was impressive, at least enough to become local celebrities. I personally recall my late grandmother telling me about the general anger in Rivera when the usual hazzan, her brother-in-law, was replaced by a mediocre and less-expensive cantor.

“They sowed wheat and harvested doctors” is a popular expression about this first generation of Argentinian Jews. Setting aside romanticism and naturalism, Jewish life in the countryside was harsh and dangerous. Not only were education and health systems extremely fragile, but a flood or a drought could literally ruin their lives. Hence, it was natural for most families to strive to move to the big cities. By the early decades of the twentieth century, Jewish life was thriving — particularly in Buenos Aires, but also in other urban centers like Córdoba, Rosario, or Tucumán.

There was a second wave of immigration that was key to the development of Argentinian Jewish culture. After the first World War, thousands of Polish, Romanian, and Hungarian and also Moroccan and Syrian Jews arrived to the country, in this case straight into the big cities. Between them there were young men who had sung in prestigious synagogue choirs in Europe, and wanted to become professional hazzanim. They found a Jewish community eager to listen to their ethnic music, not only through American or European records but also in synagogues, theaters and concert halls. There were also gifted Jewish composers and conductors ready to create fruitful partnerships with them. The “Argentinian Golden Age of Hazzanut” was starting.

The first big star of this period was Pinchas Borenstein. Born in a suburb of Warsaw, as a child he sang in a synagogue choir and at nineteen he secured his first position as a cantor. In 1923, Borenstein immigrated to Argentina. By the following year he was appointed chief cantor at the Paso Street Synagogue, one of the largest in the country, where he served for 30 years. Although Jewish integration into Argentinian society was fairly acceptable, there were still some prejudices against it, both within and outside the community. Thus Cantor Borenstein adopted the pseudonym “Pedro Borini “ in order to perform operatic arias on the radio.

The only synagogue in Argentina that surpassed Paso Street Synagogue in prestige and splendor was the Libertad Street Synagogue, where Hazzan Israel Barski became Oberkantor in 1931. He had immigrated from Soviet Russia, where he held cantorial positions in Odessa, Moscow and Minsk. Unlike his colleague Borenstein, Barski was a baritone, a much less frequent voice type among the Golden Age celebrities.

Another important name of the time was David Hitzkopf, born in 1904 in Warsaw into a family of hereditary cantors. As a child he sang in the choir of the Great Warsaw Synagogue, whose cantor was Gershon Sirota. He emigrated to Argentina in 1929, and by 1931 was a soloist of the choir of the Libertad Street Synagogue. In 1936, Hitzkopf became one of the cantors of the shul (the rishon being Barski), and in 1942 he moved to Rosario, province of Santa Fe, where he was cantor of the impressive Paraguay Street Synagogue, one of the largest in the country. He often appeared on the radio and recorded liturgical compositions and Jewish folk and popular songs.

Asking my colleague and dear friend Hazzan Gabriel Fleischer (himself a son and grandson of hazzanim) about what names should I add to this list of Golden Age cantors, he suggested Abraham Blejarovich, Aaron Gutman, Leo Fisher (his grandfather), and of course the last “celebrity” of the Golden Age, Leibele Schwartz. A Polish-born cantor and Jewish theatre star who began his career in the US and South Africa, he became the oberkantor of the Libertad Street Synagogue in 1971, where he served for twenty-two years.

By the late 70’s, newer generations felt classic cantorial art was more related to their parents and even grandparents than to themselves. The new local branch of the Conservative Movement, led by the liberal charismatic Rabbi Marshall Meyer, offered a much more contemporary and engaging experience than the old school chazonus. A new era was beginning, led by young and bold male and female cantors who moved forward with a simpler yet more congregational style.

The creation of Beit Asaf, the first (and so far only) Latin American Cantorial Institute in 1992 crystalized and expanded this new approach to davening, which became the new status quo among liberal Jewry. In a way, this new trend was a synthesis of the splendor of the Golden Age and the simplicity of earlier times. Sacrificing virtuosity for the sake of renewal was probably the only possibility for local cantorial art to survive.

Perhaps in time congregants searching for yiddishkeit will turn to old school davening once again. No matter what local Jewish life will look like in the future, the echoes of those magnificent voices that filled shuls with awe and artistry still remain as one of the finest examples of Argentinian Jewish culture.

Cantor Jonathan Kohan is a psychologist, cantor, PhD student, and Director of Beit Asaf Cantorial School at the Seminario Rabínico Latinoamericano. He writes at

, a weekly Spanish-language newsletter on contemporary Jewish life and the weekly parashah. Subscribe below!