The History Channel launched on January 1, 1995. In its first decade, it curated a cerebral yet peaceful stream of pensive documentaries, ecological adventures, and close-ups of wizened, old Oxford dons rhapsodizing about the mysteries of the past. It was a channel for the insatiate intellect, if perhaps catering its visual meals with overly stodgy fare.

Yet come the late 2000s, History discovered something new about its subject. In the past, history had been a source of sacred narrative and unsolved mysteries, and its viewers were hungry for both, down to the most footnote-like detail. But after a decade of binge-watched reality TV and late-stage capitalism, the History Channel realized that they could make more profit by forsaking the highfalutin airs of the university and church for the lure of the casino. History repackaged its historical offerings with two new stars: (1) materialism, in which the rich history of old things confers hidden value, assessed by experts for an unseen pantheon of wealthy collectors; and (2) conspiracy, that clickbait form of history in which a blotch of two-dimensional cherry-picked facts are interpreted as a revealing image, and by which the postulant believes that he is part of the community of faith which holds — nay guards— an esoteric and powerful truth.

Fed on these human frailties, recent History brought us the binge-worthy era of Pawn Stars and American Pickers; of Ancient Alien Theorists and UFO Hunters, and of the decade-long Curse of Oak Island. The documentaries are still there, though with just enough action-movie sequences in between the academics to make you feel like you’re actually watching HBO. Just check out the highlighted genres on the History Channel’s streaming and you get an interesting picture of viewers thinking about the Roman Empire, conspiracies, and extraterrestrials.

Don’t get me wrong — TV channels are businesses, and must follow their viewers. I have even watched and enjoyed some of these shows. And hey, Ancient Alien Theorists got some great news this week. But as with other junk food, I know that these shows have questionable ingredients, and are not good for me in the long run.

Healthy history is not just entertaining or fascinating, but challenges and nourishes the soul. And beyond the those cheap thrills of materialism, owning a piece of history invites the collector to make a spiritual claim to its past. This spirit has animated the great collectors of history, from rabbinic bibliophiles to nerd savants to national museums.

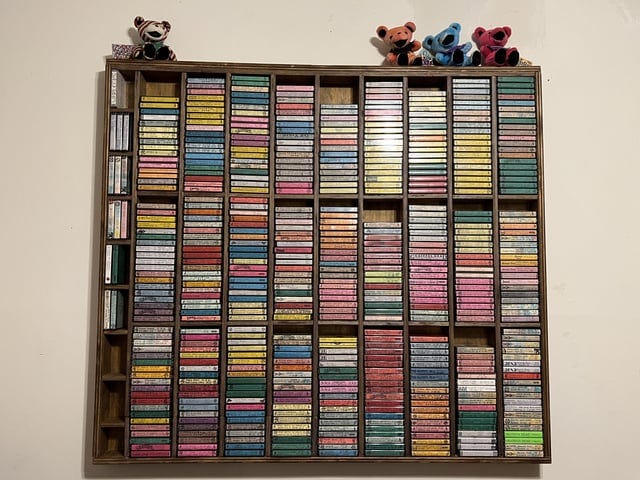

One of my favorite Shabbat hosts during my student days was a consummate collector — most memorably of bootleg recordings of the Grateful Dead. If the Dead played some twenty-three hundred shows in the twentieth century, he owned recordings of well over eight hundred of them. Like the great rabbis whose photographic memories could pass the legendary “Talmudic pin test,” my host could identify the song, date, venue, and band make-up of any Grateful Dead recording after listening to just five seconds. Owning and knowing a full-third of their total sonic legacy, he was truly possessed of the spirit of the Dead.

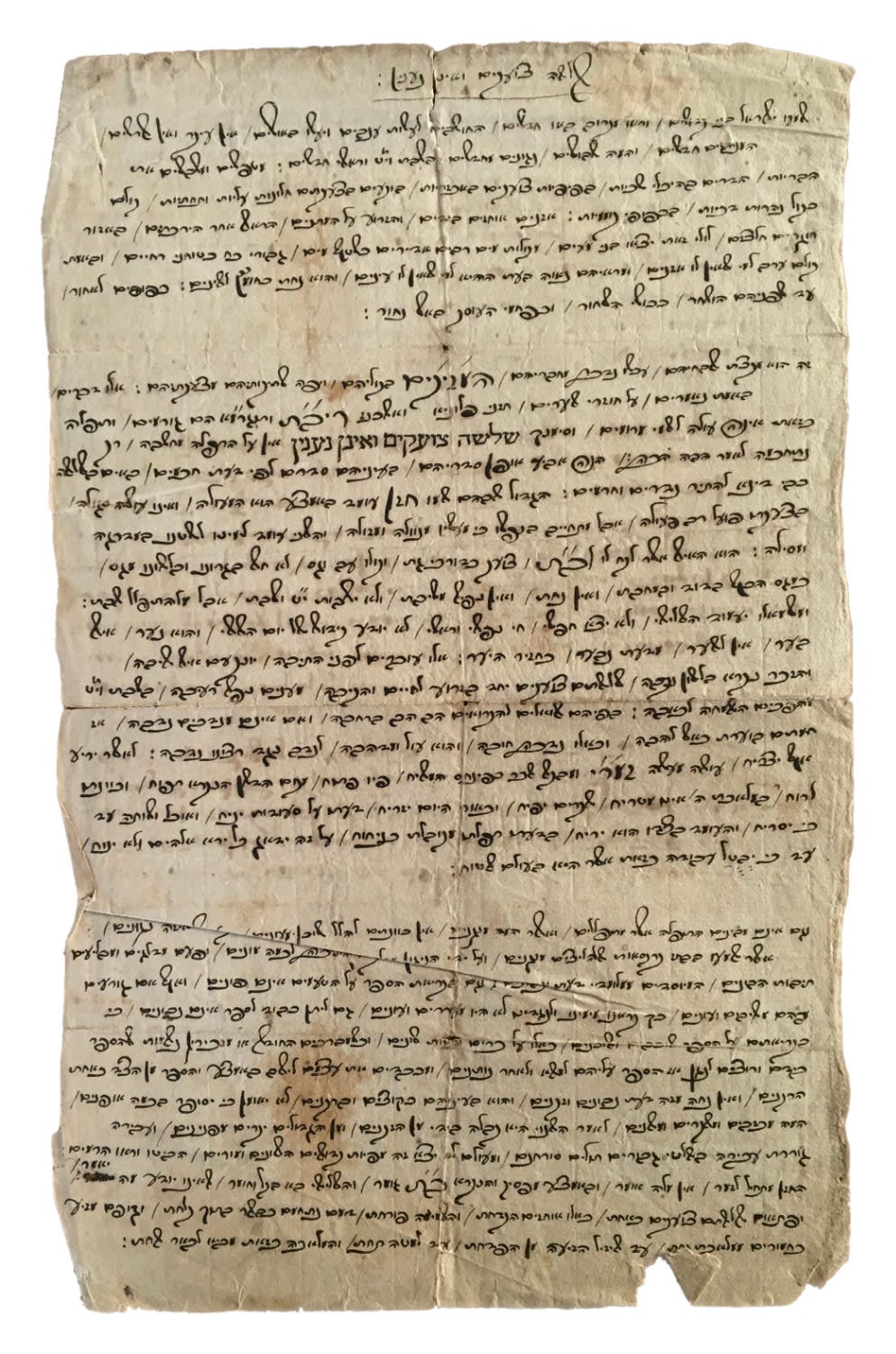

I mostly enjoy this kind of historical collecting vicariously, whether through mavens or museums. But I never deeply encountered it until I was introduced to a hitherto unknown world: the auction. While I was on a research fellowship, I was reached out to by a Judaica auction house to help write a catalog entry. The item? A handwritten manuscript of a rebuke of cantors from 1700:

This little old piece of paper floored me. It happened to be a hitherto unknown manuscript of one of the most colorful and well-known printed critiques of cantors from early modern Europe, and one that I had been brought to Oxford to study in context. The peregrinations of this paper polemic are now among the many subjects of my PhD dissertation (the full second draft of which I completed just before Passover). But without the auction world, I might have never known of this essential piece of the historical puzzle.

Ever since, I have regularly followed auctions to see what piece of unknown cantorial or Jewish music history might end up in a catalog. This thrill of discovery is common to all of us, and is part of the allure of historical research and inquiry. Yet like a family heirloom, the most important historical items are priceless— not because they have no market price, but because they tell a story that transcends commodification, and points to a life not of esotericism and conspiracy, but of deepening and evolving understanding. This is why the God of the Bible is also the Lord of History — in which a deeper understanding of this world also leads to understanding of God’s unfolding purposes for it.

Ultimately, the healthy study of history gives us deep insight and connection to the past — yet without the hubris of mastery or ownership. The more we study, the more we get discover the Socratic knowledge of how much we do not know. Rather than the owners of objects or the possessors of secrets, we are invited to become partners in a greater, ongoing, and shared quest for truth.

Wow - can't wait for your dissertation (or the popular version of it lol)! Fascinating...

Awesome piece, Matt! Can TV Guide appoint you their chief critic now? I would start reading it!