Jewish music in the Mos Eisley Cantina? Clearly, these aren’t the dreidels you’re looking for.

But did you know that the Star Wars movies were filmed in formerly vibrant centers of Jewish life in Morocco?

While researching an exciting new project in Moroccan Jewish music (which I’ll describe below), I came across the little known intersection of Jewish history in North Africa with some of the major sets of the original Star Wars films.

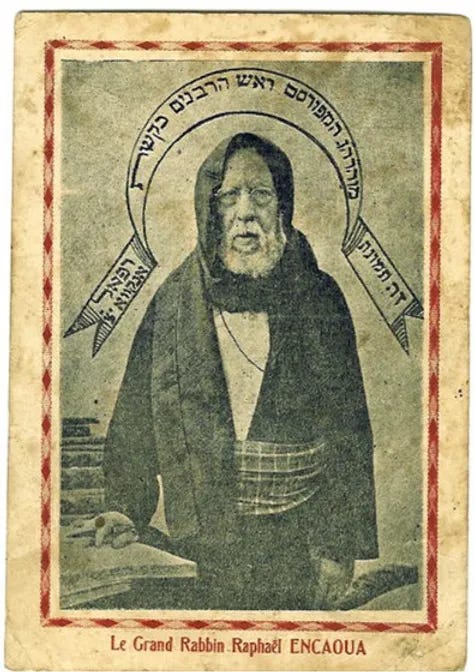

No, that’s not Obi-Wan Kenobi. But it is the Grand Rabbi Raphael Encaoua (1848-1935), one of the great sages of the Jewish community of Salé in northwest Morocco. George Lucas’ immersion in this North African setting made its impression on the unfolding Star Wars story; it is said that Lucas based the Jedi master Obi-Wan on this local rabbinic legend. Luke Skywalker’s own home planet of Tatooine was further adapted from the name of another town in Southern Tunisia — Tétouan — which once had a flourishing Sephardic community. As with so many Jewish communities following the founding of the State Israel in 1948, Arab pogroms and the threat of further violence led to the emigration of almost the entire community.

So too with the Mos Eisley Cantina. This building, together with Obi-Wan Kenobi’s home and several other sets from Tatooine were filmed on Djerba, an island off the coast of Tunisia. A long time ago, Djerba was home to one of the oldest Jewish communities in the world, with local lore dating its founding back to the sixth century BCE following the Destruction of the First Temple. The Jewish community has had a continuous presence there for many hundreds of years, even following Jewish emigration in 1948, with as many as 17 synagogues still operating in the 1980s. Yet, in the wake of a nefarious terrorist attack last fall which killed five people at the El Ghriba synagogue, Jews in this storied community are now wondering if they have a future.

Tonight is Passover (Pesach), and Jews all over the world are reciting their the master narrative — the journey from slavery in Egypt to religious and political freedom, and the defeat of the power-driven world of pagans and Pharaohs, to be replaced with the divine rule of law over a newly-covenanted nation.

The Passover Haggadah, interestingly, repeats the language “B’chol Dor Vador” —in every generation — to describe two important principles relating to the renewal of this narrative:

(1) B’chol Dor Vador, Chayav Adam Lir’ot Et Atzmo K’ilu Hu Yatza Mimitzrayim — In every generation, we should see ourselves is if we personally have come out of Egypt— as benefactors and re-enactors of this three-thousand year old liberation and covenant.

(2) B’chol Dor Vador, Omdim Aleinu L’chaloteinu / V’HaKadosh Baruch Hu Matzileinu MiYadam: We recognize that in each and every generation, an enemy arises to destroy us, yet the Holy One saves us from their hand. The Exodus is not just the primordial liberation, but also the primordial Pharaonic pogrom which, with God’s help, we have and will overcome.

What do these two things have to do with music? Throughout history, both the experiences of liberation and persecution are laden with musical power. It is no mistake that the iconic musical scene in the Torah — Shirat HaYam (Ex. 15) — is the song-child of this generative liberation — the birth of the Jewish people into freedom. Moreover, it forms the archetypal Jewish experience of going out in which we carry our melodies, like matzah, on our backs.

This phenomenon resounds across Jewish history. Sephardic Jews, following their expulsions from Spain (1492) and Portugal (1497), brought their melodies and Spanish romances all over the world, uniting them in their exile as a transnational community. During the Crusades, the Plague, and the expulsions of Middle Ages, Ashkenazic Jews transcended their trauma by uploading their music into the cloud of cultural memory in the form of MiSinai Melodies — old strands of Ashkenazic prayer chant which harken back to this formative era. In every generation, an enemy arises, an exile occurs, and a new national project is formed with music is at its heart.

But who will remember these melodies? Who will, today, see themselves as if they themselves came out of these narrow places?

I recently had the pleasure of coming across the work of Dr. Vanessa Paloma Elbaz, a research associate at Cambridge University, who is saving the indigenous music of Jewish Morocco. For fifteen years, Dr. Elbaz has been collecting and preserving the voices of aging Moroccan Jews, particularly women, to capture the musical heritage of this now dwindling community. Navigating nuanced and often difficult political and religious issues in the Jewish Moroccan landscape, Dr. Elbaz has gathered thousands of hours of music, oral history, and sound recordings, formalized as KHOYA: The Jewish Morocco Sound Archive. As you can see in her thorough article published by Dr. Elbaz in The American Archivist (2023), KHOYA is now envisioning an interactive digital platform to preserve, exhibit, and share this musical matzah — the music of affliction and the music of freedom — with the next generation.

My colleague, Rabbi Marcia Tilchin, and the Jewish Collaborative of Orange County are joining me to raise funds to support the first stage of this grand plan, which will involves uploading an inaugural digital exhibit of KHOYA material on SoundCloud, as well as curating live museum exhibits featuring KHOYA recordings at both Princeton University and at the City Museum of Gibraltar.

If you can, please do make a tax-deductible donation here to support here to support this worthy cause, and help KHOYA to provide this Moroccan musical matzah for many generations to come.

Thank you, and Chag Sameiach V’Kasher.

Note: Due to the conclusion of the Passover holiday, next week’s post will be published on Wednesday morning, May 1st.

Fascinating post! Thank you!