This is an essay about reviving the dead. But it’s also an essay about how the God of the Hebrew Bible is the ultimate musician.

Buckle up—it’s going to be a bumpy ride. But I have a feeling you’ll enjoy the final stop.

In days of yore, the resurrection of the dead was a theological engine for the hope of the Western world. For Christians, such miracles were already old news—or as they called it, good news. The resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth drove the action of the New Testament, standing as the great sign to humanity that God had finally defeated death. For Muslims and Jews, resurrection was a canonical promise yet a dream deferred, faithfully expected at the end of days. No matter what, members of the three Abrahamic faiths have long been down for raising the dead as part of God’s ultimate salvation.

But in today’s pop culture, the dead are raised into an unredeemed world. They are not resurrected or saved— they’re just undead. Thus from ‘70s horror to contemporary TV series to video games, the last fifty years have seen people get really, really into zombies. Even Minecraft, that all-consuming video game universe of eternal world-building, has mainstreamed undead encounters to our littlest minds. These are the fruits of a hope-weary and increasingly morbid culture, in which the uncertainty of redemption leads people to create new cults and to disport with death throughout the arts, like a nihilistic cultural fidget.

Jews, like others among the Abrahamic faithful, liturgically rejoice over our future resurrection in every single statutory service; it is the core of the second blessing of the daily Amidah, entitled Gevurot (“God’s powers”):

You, Lord, are mighty forever. You are the Resurrector of the dead, the Powerful One to deliver us, causer of the wind to blow and of the rain to fall.

Sustainer of the living with kindliness, Resurrector of the dead with great mercy, Supporter of the fallen, and Healer of the sick, and Releaser of the imprisoned, and Fulfiller of His faithfulness to those who sleep in the dust. Who is like You, Master of mighty deeds, and who can be compared to You? King Who causes death and restores life, and causes deliverance to sprout forth. And You are faithful to restore the dead to life. Blessed are You, Lord, Resurrector of the dead.

This is a beautiful sentiment, yet it is hard for many American Jews to take it seriously. Modern sensibilities and theologians make us doubt such an unnatural, wondrous promise as bodily resurrection. This theological pill is made no easier to swallow by the prayer’s ubiquitous, happy-go-lucky tune, which lightens the gravitas that the sacred words still hold.

This widespread melody, especially in non-Orthodox Jewish circles, was never meant to go viral. Its composer, a respected twentieth-century cantor, originally wrote it only for kids (he wrote other versions for adults). The pervasive spread of the peppy youth melody in place of more serious alternatives singed him with regret. This was not only because of the intention of the tune, but because of popular changes to the melody itself: on the words lisheinei afar, the original melody descended, reflecting the meaning of the words: “to sleepers in dust.” Yet the Jewish world evolved its own practice of going up at the end of the phrase, musically anticipating the next one.

This infidelity to both melody and liturgy was not to be born, yet impossible to stop. Once when asked about the evolution of his melody, the normally cool-headed and humorous composer experienced a rare moment of upset, saying: “Given how most people change this melody by going up where I went down, thus ignoring what the text says, I am sorry that I wrote it!"

I am sympathetic to the composer’s plight. Even when told otherwise, people always change tunes to fit their tastes. As my colleague, Cantor Richard Nadel, wrote: “Anyone who writes for congregations should get used to their music being altered. That is the nature of folk music. We may not like it, but it is a fact of life.”

But my heart also goes out as someone who cares about the text. As a Hebrew speaker, I often bristle at melodies that cheapen or sever the connection between music and liturgy. So I respect the kavanah (intention) with which the composer originally smithed his tune, hoping to capture the inner life of the prayer through word painting. As Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel taught: “Spiritual life demands the sanctification of speech. Without an attitude of piety toward words, we will remain at a loss how to pray.” A good liturgical composer, and a good cantor, must begin with this love of words.

How can one find renewed intention for this prayer in the face of campy music and theological uncertainty? We could change the tune for starters. But a perhaps more practical and fascinating answer comes from an unlikely revelation about the origins of musicology, once again from the Aristotle to my Maimonides — contemporary music critic

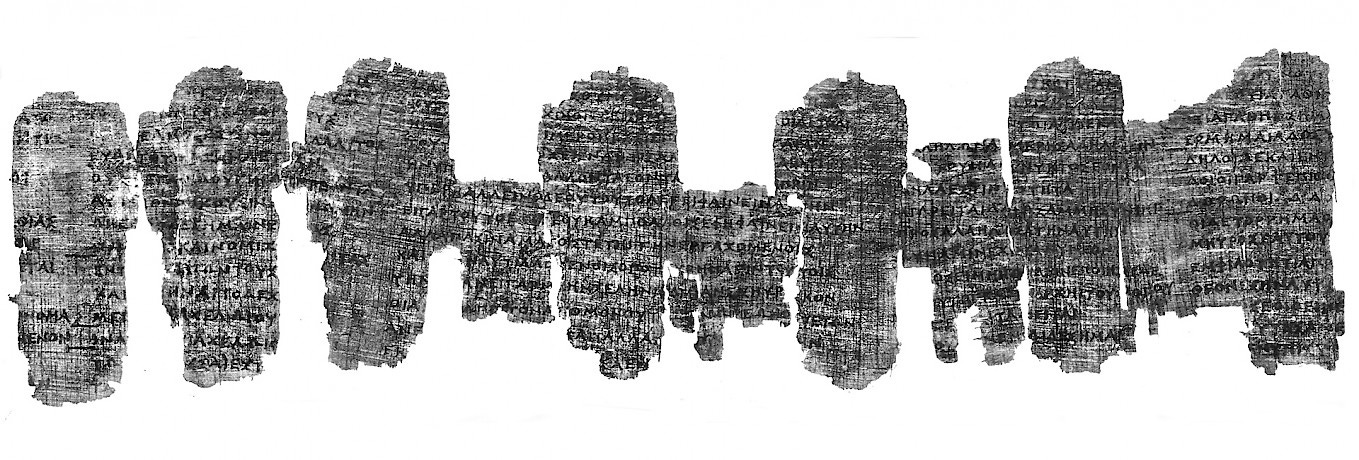

.Ted’s most recent book, Music to Raise the Dead, almost gives the plot away in the title. In his typical wide-ranging perspective, he begins by locating the origins of musicology in Europe’s oldest surviving manuscript, the Derveni Papyrus (c. 340 BCE). Among the book’s contents are the sorcerer-author’s detailed analysis of a hymn that could revive the dead. This may sound like mumbo-jumbo, but bears similarities to the Greek legend of Orpheus, who similarly wielded his musical skill to bring back his wife from the underworld. Throughout his incredible book, Ted demonstrates time and again the root of music across the world in sorcery and supernatural power, including over life and death itself. And this is still relevant today:

“Every significant aspect of the music-driven quest described in the preceding pages is not only still relevant today, but increasingly validated by science. The engine of the universe is a musical one—reminding us of those ancient myths of deities singing the universe into existence. Closer to home, doctors now remove tumors with sound. Music and sound therapy also alleviate chronic pain, addiction, dementia, anxiety, and depression. And—as we shall see below—sound even can revive comatose patients from their deathlike state.”

These powers of music should be familiar — not only from human experience, but from the Gevurot liturgy. Add in its prayer for rain, and we realize that the Amidah’s list of God’s powers are actually also those of the shaman, that musical master of transcendence and healing known throughout human culture.

Yet if musical shamanism is so pervasive, what makes the Hebraic idea of it so special?

It is that the God of the Bible is the ultimate shaman — not us. The magical thinking of shamanic traditions worldwide credit the human being as the channel for divine energies, wielding the powers of healing and revival through their esoteric musicology and incantations. The Hebrew has no different of an experience — yet acknowledges that it is not human machinations but relationship with God that resurrects the world.

This vital human-God distinction can be seen in a rabbinic legend (Midrash Tanchuma Breishit #7) in which the Roman emperor Hadrian wishes to make himself a god. Mocked by the philosophers who deny this possibility, he returns home for some solace from his wife. Yet she speaks truth to him of his own mortality, pointing out that godlike status does not follow from shamanic ability:

“The Holy One, blessed be He, declared: I restore the dead to life, and Elijah likewise restored the dead to life, but he did not say: “I am a god”; I caused the rain to descend, and so too did Elijah; I withheld the rain, and Elijah did likewise, as it is said: There shall not be dew nor rain these years but according to my word (I Kings 17:1); I caused fire and brimstone to descend upon Sodom, and Elijah did the same, as it is said: If I be a man of God, let fire descend from heaven (II Kings 1:10). Nevertheless, he did not say “A god am I,” yet you say: A god am I: In the dwelling-place of God I sit (Ezek. 28:2).”

The Bible has its share of miracle workers — yet none of them ascribe such power to themselves. The Ancient Near East’s greatest magician, Bilam son of Beor, denies that he can curse anyone whom God has blessed. Moses, in his own moment of anger, both speaks to and strikes the water-giving rock in the wilderness, and is punished because he momentarily appeared like a powerful shaman rather than a vessel of God’s might. For the Bible, and for Jews, it is God who ultimately wields power, brings the waters, heals the sick, releases the imprisoned, and revives the dead.

It is God alone who is the ultimate musician.

This realization profoundly revolutionizes our understanding of this Jewish prayer ad a description of God’s own musical ministry. And yet it also reminds us that within our own work as musicians are profound moments of imitatio dei. Those who use music can bring healing, raise the fallen, revive the dying, and use our power b’rachamim rabim — with great mercy. At the same time that the liturgy humbles us from deifying ourselves, it also reminds us that our music, when put in relationship with God, is a life-giving power reviving body and spirit.

In this morbid age, we should remember the words of Joey Weisenberg: “Music is a sign of life.” With all of our gevurot, let us use music to faithfully revive the hope and the life of our world.

Great post. Really interesting and I couldn't agree more: The standard shabbat melody for the Gevurot -- like the one for the Aleinu -- is an awful accompaniment to its text. Could you please find a way to fix that for us? :-)

Interesting post. But one thing confuses me: you describe the phrase 'lisheinei afar' as originally going down at the end, but now sung rising at the end. But it looks like your included 'original' score goes up at the end, whereas at Mosaic Law Congregation, we sing it descending over '-shei-nei-a-far'......