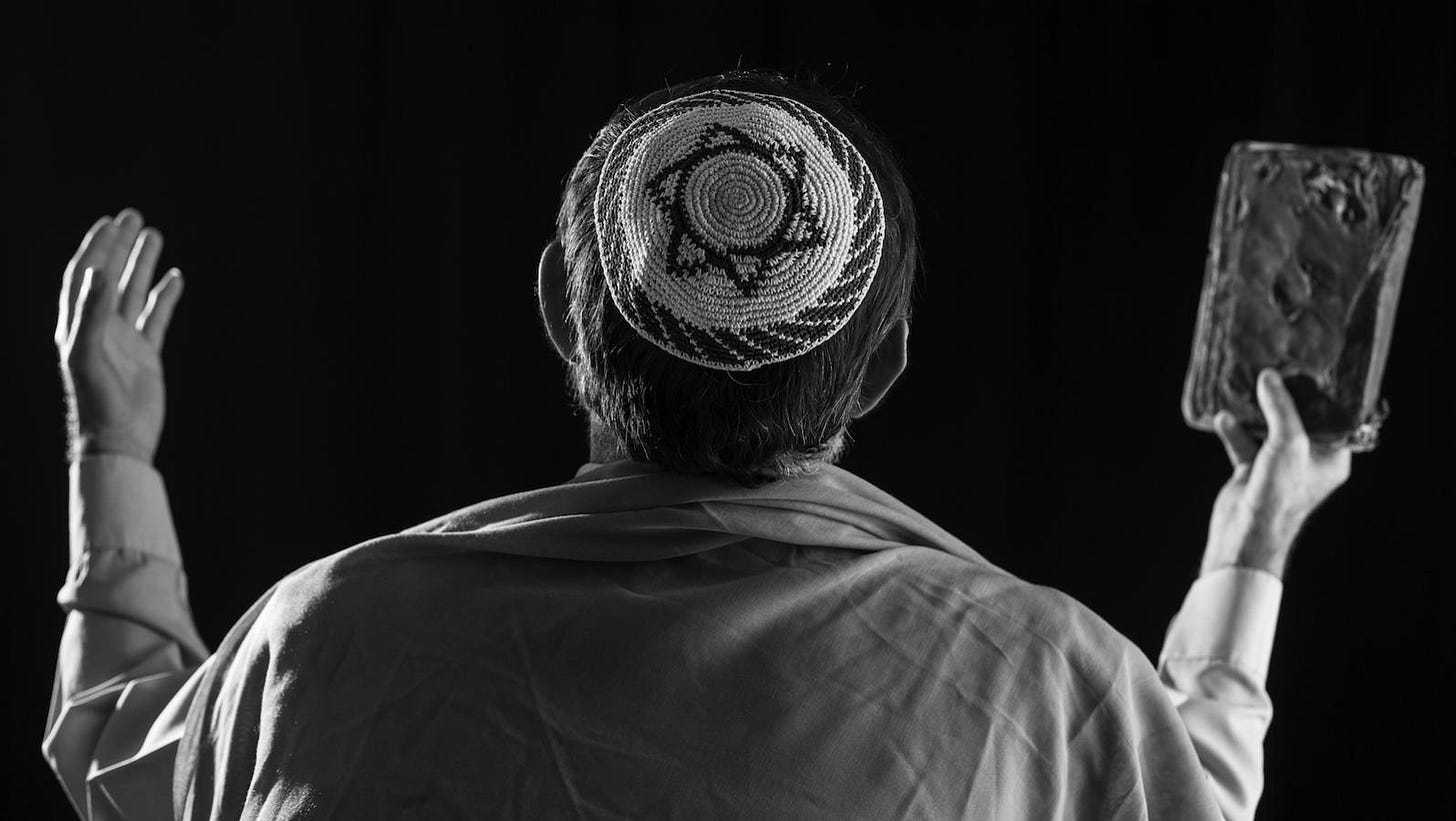

Tonight is Kol Nidre, the beginning of Yom Kippur. This year I have one thing to ask of you:

Pray for your leaders.

I’m not just talking about the obvious people who run governments and marshal influence in the world. Jews (and I’m sure other faiths) pray for this group every week, although watching any day of news coverage it seems clear that we haven’t prayed enough. But today I am asking you to pray for the leaders you see every day. This includes teachers, emergency service workers, clergy, organizers, volunteers, and the myriad of regular leaders whose dedication makes our shared life better.

We currently live in a censorious culture in which leadership can be as toxic to wield as it is to experience. Finding willing and qualified candidates for leadership roles is consequently becoming more difficult (rabbi search, anyone?). Others have lamented the causes far better than I, so I want to instead invite an alternative way of thinking about how we relate to leaders through the experience of the cantor.

One of my favorite prayers of the High Holidays is Heyeh Im Pefiyot (היה עם פיפיות). This is the congregation’s prayer for the cantors of the world. It is not a prayer that that gets a lot of attention, and many congregations either speed through it or skip it altogether. But it is a beautiful message of support and belief in the task of leadership.

אֱלֹקֵֽינוּ וֵאלֹקֵי אֲבוֹתֵֽינוּ הֱיֵה עִם פִּיפִיּוֹת שְׁלוּחֵי עַמְּךָ בֵּית יִשְׂרָאֵל. הָעוֹמְדִים לְבַקֵּשׁ תְּפִלָּה וְתַחֲנוּנִים מִלְּפָנֶיךָ עַל עַמְּךָ בֵּית יִשְׂרָאֵל: הוֹרֵם מַה שֶּׁיֹּאמֵֽרוּ. הֲבִינֵם מַה שֶּׁיְּדַבֵּֽרוּ. הֲשִׁיבֵם מַה שֶּׁיִּשְׁאָֽלוּ. יַדְּעֵם אֵיךְ יְפָאֵֽרוּ: בְּאוֹר פָּנֶיךָ יְהַלֵּכוּן. בֶּֽרֶךְ לְךָ יִכְרְעוּן. עַמְּךָ בְּפִיהֶם יְבָרֵכוּן. וּמִבִּרְכוֹת פִּיךָ כֻּלָּם יִתְבָּרְכוּן

Our God and God of our fathers, be with the mouths of those who have been sent by Your people the House of Yisrael, who stand to offer fervent prayer and supplication before You, on behalf of Your people, the House of Yisrael. Instruct them what to say, teach them what they shall speak, disclose to them what they shall ask, make known to them how they may glorify You. In the light of Your countenance may they walk, [their] knee, unto You may they bend, Your people, with their mouths, may they bless, and from the blessings of Your mouth, may they all be blessed...1

This is the kind of support that leaders of any kind would want to experience. In this prayer, the community voices its encouragement and its affirmation of a deep connection to them as leaders. Longer versions of the prayer include the line “your people surround them like a wall,” showing how the community envelops the leader in solidarity with their sacred task.

More than one rabbi I know has told the story of visiting a black church and being vocally encouraged and supported by the congregation. As the guest speaking rabbi or the local pastor would try to find his words (particularly in moments of speaking extemporaneously), the parishioners would call out “Help him Lord, Help Him!” This gave the leader the courage to speak from the heart.

Prayer leaders and musicians, especially on the High Holidays, need this assurance as well. At the core of the cantor’s task is praying with heartfelt intention on behalf of the community that sends her. Mutual good faith thus opens the hearts of both parties. This is true of music in general: from the opening band to the top-tier orchestra, ensembles search for affirmations of the sonic covenant between them and their audience.

These affirmations can be hard to come by. A thoughtful reader wrote me recently about last week’s article on cantorial confession, lamenting the devolution of liturgical moments like Hineni into concert pieces seemingly at odds with prayerful statements of humility.2 I agree that this a problem.3 But it doesn’t mean that moments of musical faith-sharing like Hineni can’t channel the authentic feelings and religious sentiments of both prayer leader and community. What makes these moments “work” is partly the quality and intention of the prayer leader, but primarily the relationship of the leader to their gathered community and the community’s choice to focus on either judgement or support.

Bridging this gap can be especially hard for cantors and choirs. So often, the relationship between congregation and its musical representatives can devolve into a tug of war for musical power. At its worst, a faction within a congregation develops the sense that the choir is a class of middling musical aristocrats unworthy of leadership. Yet they are protected by the musical autocracy of the the cantor, and these musical elites hoard precious moments of music and prayer while their bitter congregant-subjects simmer in silence, waiting for the weight of tradition to release just enough to stage a cultural coup d’état.

But we don’t need the synagogal ghosts of Robespierre, we need relationship instead.

I have therefore always longed for a ritual for synagogue choirs and musicians. The cantor and choir should come forward and walk through the congregation, and as they pass, each person should vocalize for them a short blessing, as simple as saying “please pray for us” or “we are with you.” Before COVID, I could even imagine a laying of hands, drawn from the biblical commission of the Levites to do the service of the Lord on behalf of the people. And this intention-setting could be musically accompanied by a niggun (wordless melody) from the congregation. The ritual moment created, at its best, could help prayer leader, choir, and community unite in mutual purpose and mutual good faith.

Without such good faith, leadership flounders as stiff-necked people pick sides over problems minor and major, leading to wasted energies, communal fraying, and even dissolution. It is for such reasons that Rabbi Chanina taught in Pirkei Avot: “Pray for the welfare of the government, for were it not for the fear of it, men would swallow one another alive.”4

This does not mean we should not hold our leaders to account, or neglect to uphold laws and standards based on our relationships. Every institution and class of leader has born the sins of such neglect, which has damaged trust and destroyed lives. There is much to repent.

As community members, we must acknowledge that those who embrace the difficult task of leadership are whole human beings who want to know that their service matters. Their authority may obscure their humanity to us, but it is certainly not obscured to their Creator. It is for this reason that every cantor recites: “Hineni he’ani mi’ma’as…I stand here, impoverished in good deeds, perturbed and frightened in fear of the One who is enthroned upon the praises of Israel. I have come to stand and to plead before You on behalf of Your people…”

So this year, pray for our leaders. Pray for them to do their best, to be humble, to walk in light and goodness. And pray for yourself to do so as well.

Let us not be torn apart, but help each other to rise to our best selves, each in our own vocation and capacity. If we can pray for each other, we can build shared a life. May we be inscribed and sealed, together, in the Book of Life.

This text has been shortened for length. You can read the full prayer here.

Certainly the world has experienced its fair share of cantors calling out at an infelicitous fortissimo: “He’ani Mi’ma’as! I am nothing!” This reminds me of an old Jewish joke.

This deals with the Jewish art of leadership going back to Moses, and the question of how to carry a message without being mistaken for the ultimate Messenger. I will write more on this at a later date. For those interested in big questions of Judaism and leadership in the meantime, I highly recommend

by Rabbi Josh Rabin for a consistently well-read and insightful approach to both subjects.Mishna Avot 3:2

Should be trending—