Today I want to speak to you about cantors and comedy. But first, a time-sensitive matter:

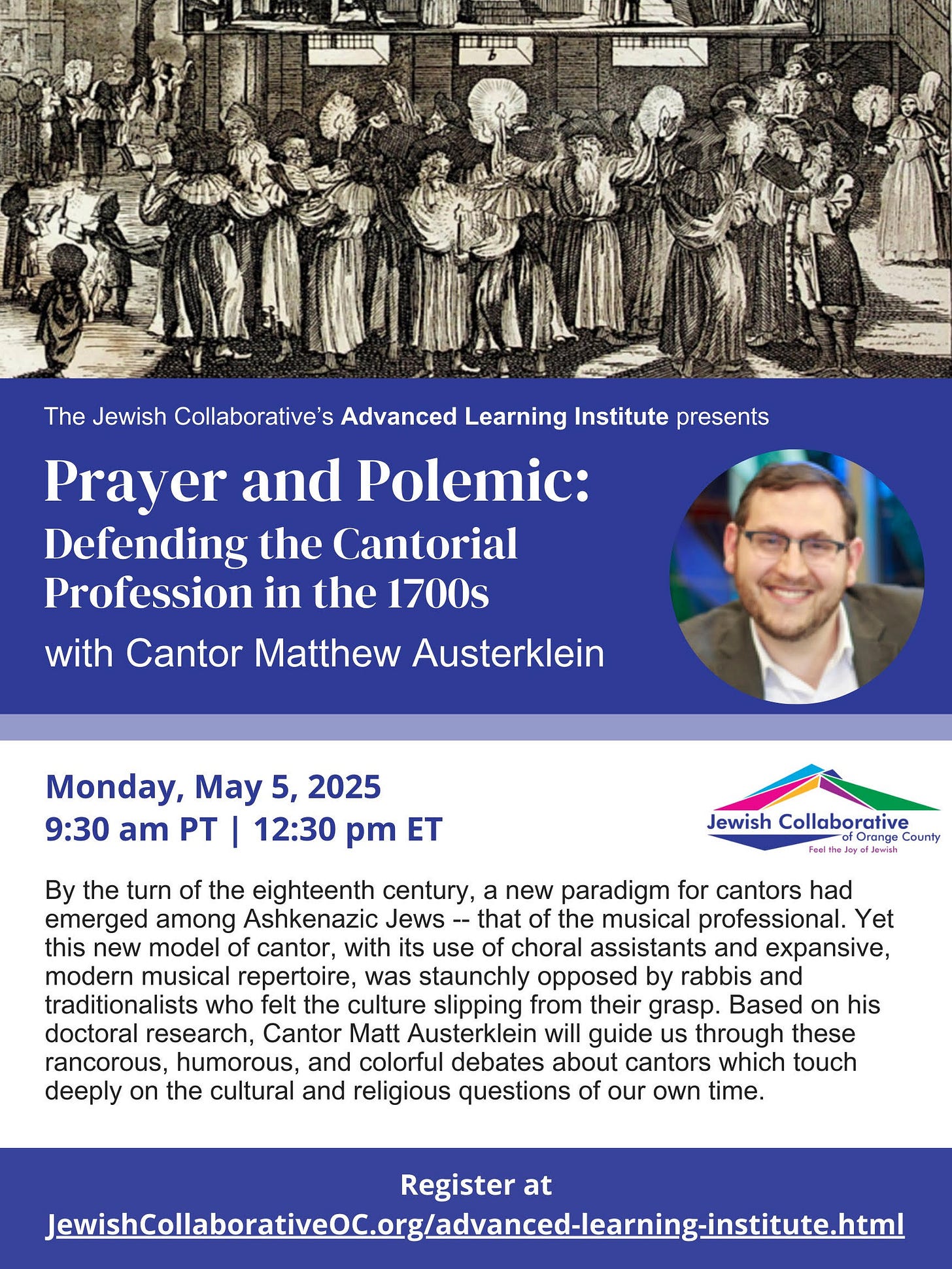

TODAY (Monday, May 5th) at 9:15am PT / 12:15pm ET, I am teaching a session about my doctoral research on cantors in early modern Europe. This means fifty minutes of musical change, angry rabbis, and cantors defending their newfound spirit and professional identities. Plus a lot of eighteenth-century cantorial humor, both by cantors and at our expense.

You can sign up here: https://www.jewishcollaborativeoc.org/advanced-learning-institute.html. The lecture open to all, and is free / pay-what-you-will.

And now for something completely different (almost).

I just flew back from Los Angeles, and boy are my arms tired!

Okay, I’ve told better jokes. After all, I grew up with one of America’s funniest rabbis, and I had my bar mitzvah party at an improv club. But when not hearing Torah-infused humor in the synagogue, I spent my own time listening to hours upon hours of sketch and stand-up comedy. And I don’t mean just the contemporary stuff — I mean the old stuff, like Abbot and Costello, Groucho Marx, and Henny Youngman.

Leonard Bernstein famously attributed his sense of the spoken word to his childhood rabbi, Herman H. Rubenovitz. Serving at New England’s oldest Conservative synagogue, Congregation Mishkan Tefila, Rabbi Rubenovitz spoke with an elevated, Oxford-inflected English which made a deep impression on the young composer. Bernstein wrote: “He gave me my first notion of public speaking, of declamatory passion and timing, a sense of balance and moderation in reasoning; a liberal view of argument, an enormous sense of dignity, and the basic divine element in man.”

While my English elocution is ever affected by my own exposure to British comedy and Elizabethan verse, it has been the world of stand-up that has perhaps most influenced the way that I talk. In a sermon as in stand-up, a spoonful of sugary humor helps the moral medicine go down.

The cantorial world has long seen its share of comedians, though I am certainly not counted among the best of them. This role dates back to at least the seventeenth century, in which cantors featured in some of the first ever Purim spiels. Contemporaneously, cantors also sometimes took on the role of the badkhn, or wedding comedian. This was a job for someone with serious literary bona fides. As Jean Baumgarten points out, the badkhn was “a repository of Jewish religious culture and oral tradition, invested with the role of transmitting songs and music, moral messages, and wise counsel along with the fundamentals of Judaism.”

Today, the role of the cantor-comedian has been brilliantly filled by new generations. Jackie Mason—a rabbi first by training— could do a mean Passover kiddush. The twice-decorated UK Eurovision singer Cantor Simon Spiro rates as one of the cantorial world’s most hilarious stars (and one of my favorite chazonim). One of the hit Jewish comedians of our own day, Modi Rosenfeld (above), was trained first as a traditional orthodox cantor at the Belz School of Jewish Music. And still continuing in the classic borsht belt tradition is the great Herschel Fox, Cantor Emeritus of Valley Beth Shalom in Encino, CA. For those of you who have seen his shows, don’t worry, this one is safe for work:

I can’t hold a cantorial candle to these guys. But I will admit that I use my mental library of risible rhetoric in my lectures and homilies. No one should ever pay me to do comedy professionally, but knowing the art form does provide a good training in communication skills.

That said, I will say something that might shock you: I actually don’t like stand-up comedy sermons. A good dvar torah can make you laugh, but it must pivot towards wrestling with deep and serious religious questions.

There’s a difference between utilizing techniques from one cultural form and adapting so much that you change the goal of your own communication entirely. Cantors and prayer leaders have long been guilty of such overreach, making prayer about beauty or entertainment when it is truly supposed to be a love letter to the One to whom it is addressed. The same is true in the sermon and the lecture as well — if I do my job right, the entertainment value never effaces the educational and moral value.

But I will close with one exception: the Latke-Hamentasch Debate. Originating at the University of Chicago in 1946, this “deliberately humorous” academic symposium pits leading scholars and professionals against each other to advocate for the ultimate supremacy of the Latke over the Hamentasch (or vice-versa). Over the last seventy years, the event has expanded to include many college campuses across the United States, and even some synagogues as well.

I was blessed that in my first pulpit, Congregation Beth El in Bethesda, Maryland, a well-attended and vigorously-researched Latke-Hamentasch symposium was already a time-honored tradition, established there by my colleague, Rabbi Bill Rudolph z’’l. Our debates featured fascinating and erudite panelists drawn from the limelights of DC-area professional class. As their new cantor, I received an invitation to throw my hat into the potato- and pastry-filled ring.

On what basis could I judge the Latke vs. the Hamentasch? Only on the merits of what I knew best — Judaism. You can watch the recording below, and see if you agree. I will only ask the pardon of my Texan friends for one joke towards the end which shows the limits of my ability to change sports team loyalties as a longtime Washingtonian.

From the badkhn to the bima, humor has always lifted our spirits and lightened our burdens.

Or as Eric Idle once wrote — the opposite of gravity is levity.

I have always been for the Hamentasch. Thank-you for the videos and your sense of humour. Enjoyed.