A View from the Ark

Alex Weiser's Chamber Opera, "The Great Dictionary of the Yiddish Language"

“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” – Ludwig Wittgenstein

To know a language is to behold an entire world. Formed by centuries of nature, history, and Providence, each tongue contains cascading layers of cultural and ethical inheritance which define not only its words but the very grammar of its meaning.1 The Scots have hundreds of words for snow, Hawaiians have 65 words for sweet potato, and Somalis have over forty words for camel. Yiddish, nebuch, is blessed with many curses. Thus, in our post-Herderian era, language becomes the essential marker of a historic people in its progressive evolution.

Yet all such evolutions are defined by conflict. As the great Yiddishist, Max Weinreich, famously quipped: “A language is a dialect with an army and navy.” The evolution of language charts the rise and fall of peoples and the waxing and waning of their cultural legacies.

So what happens when the world threatens to wipe out your language — the very grammar of your soul?

In Hebrew, the word for “ark” is identical to the term for “word” — tevah (תֵּבָה). The biblical tevah exclusively indicates a container, specifically a ship or chest. In the Torah, this tevah preserves life. Both Noah and Moses are sheltered in a tevah — a floating chest which protects their hopes and futures and allows them to escape certain death. So when did an ark become a word?

During the rabbinic period, tevah came to signify containers of meaning rather than containers of living beings, possibly because of the rectangular, “box”-like shape of Hebrew words in scribal art. What’s more, the word tevah evolved into a defining aspect of Talmudic prayer, as the phrase “to go down before the ark (yored lifnei hatevah)” came to indicate the liturgical leadership of the sheliach tzibbur (prayer leader).

The origins of this transformation are still unclear; yet the homiletic connection has not been lost by generations of rabbis. As my better half, Rabbi Elyssa Austerklein, once wrote: “Only Noah who has already entered the tevah, meaning God’s word, can build the box — the container that will sustain God’s holy creation during the flood.”

Thus both before and after Herder, a word contained — and even saved — a world.

These diluvial dangers strike at the heart of Alex Weiser and Ben Kaplan’s recent operatic collaboration, The Great Dictionary of the Yiddish Language. The new 50-minute chamber opera, which premiered in New York last fall, follows the true story of one generation’s linguistic Noah, Yudel Mark (1897-1975)—the single-minded scholar who committed his life to compiling the first fully-comprehensive Yiddish dictionary. Working feverishly in the shadow of the Holocaust and the deterioration of Yiddish culture in postwar America, Mark set out to surpass Noah himself, keeping every single Yiddish word afloat in print above the flood of assimilation and cultural malaise.

Through Kaplan’s creative storytelling, the idealistic Yudel (soaring through Jason Weisinger’s deeply vulnerable yet heroic tenor voice) is haunted by a mystical chorus of Yiddish letters. These three Alefs —Komets, Pasekh, and Shtumer —represent divine emanations of the soul of Yiddish language. Leading this supernatural female trio, which serves as a sort of “drei Damen” on Yudel’s Tamino-esque journey, is the pathos-filled and sometimes comic “Shtumer (silent) Alef.” With the able vocalism and emotional clarity of mezzo-soprano Kristin Gornstein, the Shtumer Alef stirs the sentimental and existential embers of Yudel’s preservationist mission.

Brooding on the precious nature of every Yiddish word, each with its mystical holy spark, Yudel Mark reached a colossal achievement, gathering a gob-smacking collection of over 200,000 words, including rare and new words which form Yudel’s vision for the Yiddish future. Yet this ambitious project ran afoul of the very institution which first gave it life — the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

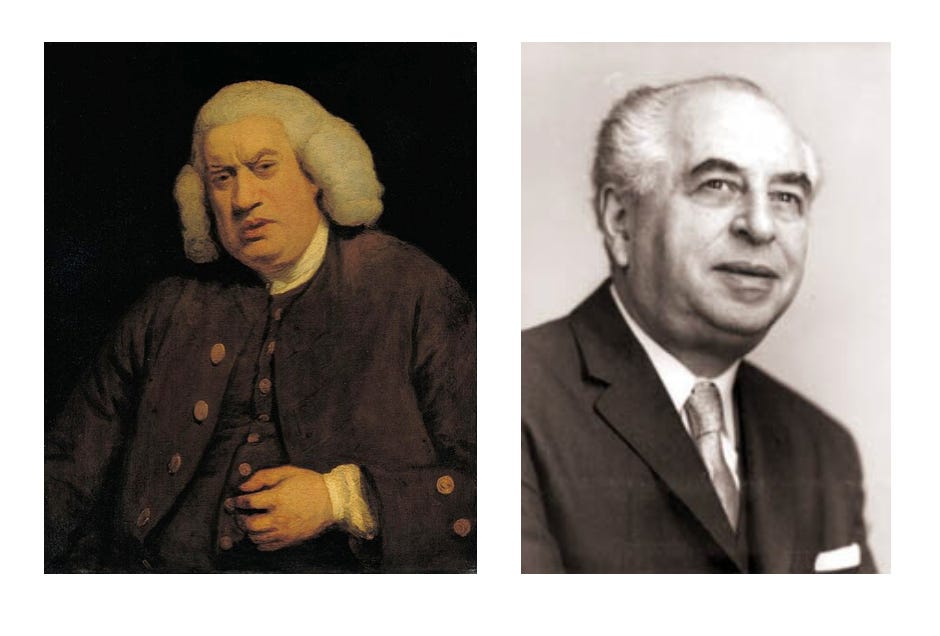

Max Weinreich, whose dignified baritone role is beautifully handled by Gideon Dabi, was the co-founder of YIVO, stewarding the hallowed institution from its origins in Vilna to its Post-WWII home in New York. Mark’s ambitious project was too ungoverned for the rigorous Weinreich, breaking with scholarly dispassion and dedicating four volumes alone to the letter aleph. The dictionary also violated YIVO’s sacred Takones — the standardized rules of Yiddish spelling and grammar which gave dignity and scholarly weight to the institution’s publications.

As these two scholars battle throughout Weiser’s opera, they reflect two approaches to saving culture: open vs. closed, generosity vs. order, and folk vs. elite. If Max Weinreich was Yiddish’s Varian Fry — saving the highest culture of Yiddish words from the tidal wave of history, then Yudel Mark was its Oskar Schindler — making a precious list with every word that he could save.

Composer Alex Weiser is the master of nostalgic, velvety harmonies which evoke the spirit of New York without a hint of klezmer. His approach in Great Dictionary of the Yiddish Language is full of Sondheimian textures, especially similar to those of the Broadway composer’s own brooding one-act, Passion (1994). Whereas Sondheim often declares war between his melody and accompaniment, Weiser’s atmospheric orchestrations support his meditative word-painting, allowing the libretto to speak elegantly for itself.

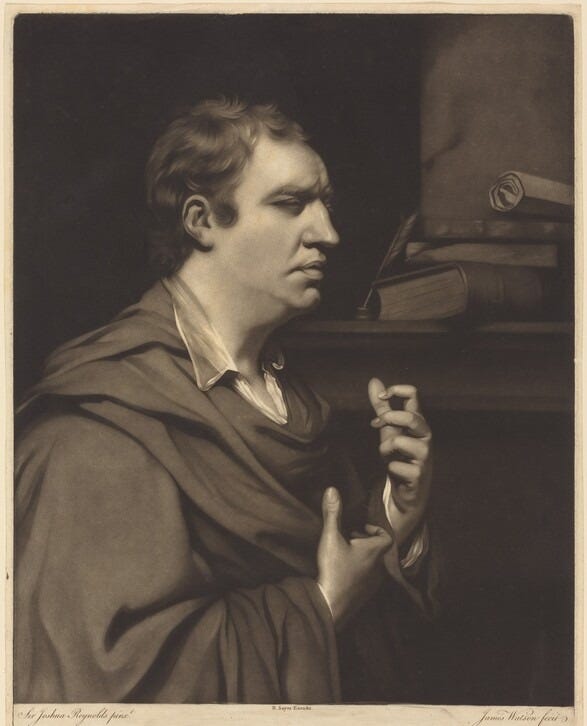

Yudel Mark’s eccentric and boundless commitment to the Yiddish language recalls an earlier dictionary project prepared by an equally mercurial linguist — Samuel Johnson, author of the first Dictionary of the English Language (1755).

Johnson’s English dictionary came not from the desire to save a precarious civilization, but from the quest to forge a new one. In the mid-1700s, the union of Great Britain (comprising England, Scotland, and Wales) was barely a century old. Both Italy and France had produced their own dictionaries, demonstrating the richness of their languages and completed by teams of advanced scholars. It was English which needed a competing dictionary, giving dignity to its cultural wealth.

Samuel Johnson, a bookseller’s son of poor health, depression, and behaviors likened to Tourette’s syndrome, was the man for the job. In nine years, he almost singlehandedly created a dictionary of over 42,000 words and 114,000 quotations from the great works of English literature, thus documenting the scope and value of English language for a nation in search of itself.2

Both Johnson and Mark knew the same truth about language — that it is a container for the wisdom and spirit of a people. Yet while Johnson’s English still dominates the world, Mark’s Yiddish remains in perpetual crisis, even as it is beloved by academics, artists, and Hasidim. There are no easy solutions to the problem, nor do Kaplan & Weiser’s work claim there to be any.

It is no small irony that they themselves are staff members at YIVO, the very institution at the center of their opera, and which serves as America’s academic “ark” for Yiddish language and study amidst the floodwaters of Ashkenazic cultural drift. And that is the opera in a nutshell: a view from the ark — which is also a view from the word.

Whereas Greek thought considered time as linear, with the future ahead of us and the past behind us, Hebrew thought felt time in cycles. The Hebrew language reveals this in its use of prepositions to describe time: The past is l’faneinu — literally “before/ in front of us,” and the future is “achareinu” — after us / behind us. This reflects the essential orientation of Hebrew thought as focused on the past, and the root of our orientation to God as the Lord of History. For more on this, see Thorleif Bowman, Hebrew Thought Compared with Greek (1960).

When comparing his efforts to the large teams of linguists at the French academy, Johnson quipped with nationalistic English wit:“ This is the proportion. Let me see; forty times forty is sixteen hundred. As three to sixteen hundred, so is the proportion of an Englishman to a Frenchman.”