I write a lot these days about old music. But just five years ago, it was the exact opposite.

Five years ago, I wrote a book about Jewish a cappella.

When I was in high school, I was in a Jewish a cappella group started by my intrepid cantor and now colleague, Elisheva Dienstfrey. When she brought Pizmon, the co-ed group from Columbia/JTS, to visit our synagogue, I was totally starstruck. To me, these were the “cool kids” who bridged the choral, pop, and Jewish worlds in all the best ways.

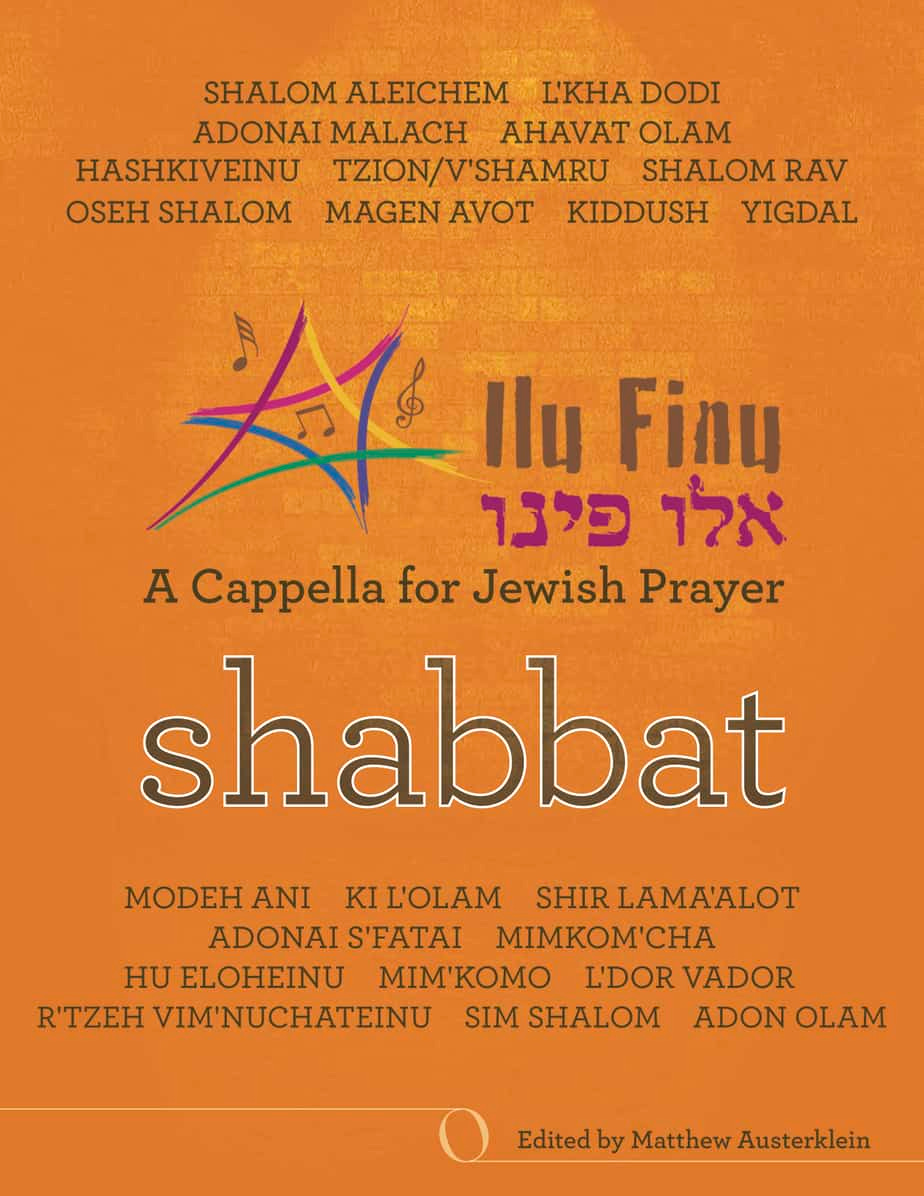

In college, I tried to start a group of my own. Four years later, in cantorial school, I finally succeeded, forming my own a cappella-style ensemble, the Wizards of Ashkenaz, with which I still perform (almost) annually. And in my first pulpit, I was lucky to serve as a judge for its then national performance competition, Kol HaOlam. But even more importantly, I was blessed to be the cheerleader and occasional coach for a high school group based at my synagogue. It was through my work them that the book —Ilu Finu: A Cappella For Jewish Prayer —came into being. The book comprises twenty-two pieces in a cappella style for use in services, but it is also a deep resource for a cappella practitioners on the spiritual stakes of their art.

This week, I offer you the introductory essay to that book.

In future weeks, I will write more on the current state of the genre, particularly at the collegiate level and in the wake of October 7th. Some of the references below will describe the pre-covid a cappella scene, yet the timeless question of the essay remains: Can Jewish a cappella be more than a performance?

Read below to find out.

Thank you for reading Beyond the Music! If you enjoy reading this newsletter, please consider supporting me with a paid subscription.

Finding Our Voice, Expanding Our Range — Exploring A Cappella as a Mode of Communal Prayer

Who knew a hundred years ago, or even twenty years ago, that the Jewish music culture of North America would be irrevocably defined by the growth of Jewish a cappella. From a mere handful of upstart college groups founded in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Jewish a cappella scene has grown by leaps and bounds, riding the ascending wave of a cappella popularity on college campuses and in American popular culture, and demonstrated by the success of super-groups like Pentatonix, the Pitch Perfect movies, and the Glee TV series.

Thirty years after its genesis, the Jewish a cappella scene now boasts its own festivals, national competitions, high school groups, well-known touring professional ensembles (including a half-dozen in Israel), post-collegiate ensembles in major cities, and over forty active groups on university campuses. Most recent is the phenomenon of humorous, Jewish holiday-themed viral music videos, often produced by Jewish a cappella sensations Six13 & the Maccabeats, which quickly set Jewish music trends across the country through social media.1 Synagogues, Jewish Community Centers, and even the White House Hanukkah Party all now regularly call upon Jewish a cappella groups to musically represent Jews before regional and national bodies.

But what of representing them before God? Does Jewish a cappella have a life after college or outside of Youtube? Can this purely vocal art form provide contemporary Jews with an accessible vehicle for prayerful experience, as well as an effective tool for strengthening communal worship? This book was born out of and seeks to address such questions, as well as raise others for consideration.

My first job out of cantorial school was at an incredibly vibrant American synagogue, Congregation Beth El of Montgomery County, situated in the Jewishly-dense suburbs of Washington, DC. Among many exceptional features of this community was its high school Jewish a cappella group, called Marak HaYom.2

Its singers were often involved in the area's rigorous high school music and theater programs. But its uniqueness lay in that it was run entirely by the teens themselves. The group independently elected its own music director and business manager, held auditions, and met each Sunday in members' homes for two hours of rehearsal (importantly followed by informal social time and a festive bagel brunch). The group sang by request at the synagogue's many bar and bat mitzvaha to the delight of families and guests, as well as at Purim and other community gatherings.

As I would watch them come up to the bimah each Saturday, I would often marvel at the beauty of their singing. But then I would also find myself reflecting, that what I was experiencing was less a prayer than a performance. And at the time I could not, and often still cannot, determine – is that a bad or a good thing?

The word “performance” is a dirty word in the synagogue world of the twenty-first century. It reeks of inauthenticity – of performers who seek to entertain or present themselves rather than to earnestly pray for the congregation (or, on behalf of others). To speak of performance further evokes an underlying distrust of previous generations of worship aesthetics that emphasized, rightly or wrongly, the musical excellence and prayerful expression of the synagogue's designated musical elites (most often the cantor and/or choir). This era produced sacred compositions of great artistic ingenuity, some of which could be equally appreciated in the synagogue or the concert hall. But artistry is not always the handmaiden of prayer, and virtuosity can quickly devolve to a mundane appreciation for he who possesses such musical gifts rather than He who endowed them.

Concerns about “prayer vs. performance” have thus often followed cantors, who are both sacred singers and keepers of generations of synagogue music tradition, as well as supporters and facilitators of a community's authentic prayer experience in the moment. These past fifty years in particular have witnessed a widening gap between congregational demands and traditional cantorial aesthetics. Many of my colleagues would be rich men and women indeed if they had a dollar for every time a search committee emphasized that they didn't want a “performance” in prayer. Yet I believe that this phenomenon points to deeper truths about our era that transcend mere questions of style.

We live in a time when leadership (both that of the prayer leader, and indeed of God Herself) is often defined by being a “Guide on the Side” rather than a “Sage on the Stage.”3 Politically, musically, and theologically, many American Jews express having experienced the hollowness of traditional institutions and hierarchical models of leadership. They have also expressed their desire to connect to God and each other through communal singing – emphasizing the “active” experience of singing and praying as one.4 When we are asking for prayer to not be a performance, weare often asking for a sense of authenticity in the prayer leader, humility in her vocal style and choices, and skillfully-led communal singing that privileges and foregrounds the voice of the congregation above that of the cantor. Essentially, we are asking our musical leaders to follow the rabbinic dictum: “Al Tifrosh min HaTzibbur” – do not separate yourself from the community.5

This approach engenders obvious tensions with artistic styles of music, which have exerted a strong influence in American synagogues since the nineteenth century. This music, based on earlier European synagogue traditions, often calls for a degree of expertise not attainable by a layperson. Cultivated musical groups of all kinds require specialized singers, preparation, rehearsal, and an opportunity to be heard. Like the levitical orchestras and choirs of Temple times, such music inheres a separateness between the musical roles and responsibilities of the sacred musicians and those of the congregated worshipers. Cantors have traditionally been the initiated masters of those vocal styles and repertoires, particularly the synagogue music of the nineteenth and 20th centuries, that have relied on musical cultivation and indeed hierarchy. This has led to a paradigmatic struggle for cantors of all stripes to reorient themselves in the communal singing tidal wave of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Contemporary a cappella music represents a unique bridge between these cultivated and communal approaches to music – between art and folk. Like all choral or ensemble singing, a cappellarequires a modicum of vocal skill, practice, and preparation. Much that is sung, a congregation or audience cannot readily do. And yet a cappella groups also represent a version of the more egalitarian values that inhere in the communal singing movement: Solo singing is shared equally among the group members. Much a cappella arranging is done orally, with each voice taught a series of repetitive “riffs” that provide harmony and augment the solo melody line. A cappella groups also have a norm of memorizing their music and not relying on sheet music, thereby sharing more personal presence with their listeners – a vital lesson in connecting with the congregation that cantors and choirs would do well to learn.

Over the years, as I sat in synagogue listening to Marak HaYom, I wondered at the possibility of transforming this excellent, cultivated ensemble into a more integrated part of the prayer experience. They presented themselves as the potential modern counterparts to the meshor'rim – the choristers of the traditional synagogue, who would not only sing pre-composed pieces but would sensitively accompany the liturgy with spontaneous harmonic undertones and emphatic “amens”to the vocal improvisations of the cantor.6

A cappella groups have rarely before been considered as prayer ensembles.7 And yet the a cappella movement represents an animated, growing force in North American Jewish musical life that captures the spirits and ignites the musical passions of thousands. Dozens of rabbis and cantors were first turned on to the power of singing, and even to Judaism, because of their experience in a cappella groups. Indeed, one of the most under-leveraged and under-served populations in Jewish life today are ex-a cappella singers, who left college and found no outlet (or use) in Jewish communities for their singing passion and experience. The love of a cappella, like that of all music, is also a deeply spiritual matter, touching upon deep human emotions and soulful longings. Is it not from within these depths that prayer becomes possible? Cantors know well that some of the most committed Jews in their communities are those who have regularly participated in a synagogue choir. Is the a cappella group not the next frontier for spiritual engagement and collaborative contribution in the context of the wider community?

However, the matter is not so simple after all. If the goal is to create a musical ensemble equipped to facilitate a prayerful experience, this requires considerable reflection. Numerous questions arise, such as: How might a musical group transform into a liturgical ensemble? How might one adapt the passion for upbeat performance with a Jewish pop ethos for the purposes of heartfelt, prayerful singing? How could the hierarchical dynamics of specialized ensembles work together with the modern musical models of equality and accessibility (both vocally and otherwise)?

Closing this gap, and a finding place for a cappella ensembles in Jewish worship, would require much thoughtful consideration, and yet, I believe, would be well worth the effort. For starters, groups would need a degree of liturgical knowledge; their own understanding of the words and authentic kavannah (emotion/intention in prayer); sensitivity to the flow of the prayer service; and perhaps even spatially positioning the ensemble in a way that emphasizes its identification with the congregation (around the lectern, in the seats, or facing the ark, rather than singing/praying at the congregation).8 And most importantly, it would demand repertoire that was both sensitive to the liturgy and which activated the best qualities of the contemporary a cappella style.

It is to provide these very supports for cantors, rabbis, educators, lay leaders and community members to incorporate Jewish a cappella music and singers into their communal and liturgical repertoire that has inspired the creation of this book.

Our range of compositions was gathered from two principle sources – collegiate arrangers and Jewish music professionals. In 2017, the Cantors Assembly launched a nationwide contest – the Ilu Finu Jewish Songwriting Competition - which called for college students in North American Jewish a cappella groups to submit their best original compositions and arrangements of the Jewish liturgy. I created this project together with my colleague, Hazzan Benjamin Tisser, who also hosted the finalist concert for our winners in January of 2018. Eight beautiful collegiate arrangements were given recognition and are included in this book. Following the contest, we solicited and gathered additional arrangements from professional Jewish a cappella and vocal jazz arrangers, together with cantors from Jewish a cappella backgrounds. The result is the book before you – a collection of twenty two pieces of Jewish liturgy, designed for spirited and sensitive inclusion in a worship service.

The styles included in this book are diverse. Many arrangements feature the variety of textures, vocal sounds, and percussive elements that are typical of the a cappella genre, while a few will have much more in common with the choral music tradition. These pieces also range in their approach to the role of the congregation – some provide mostly textural and harmonic accompaniment to a communally-sung melody; some involve regular interplay between the a cappella group and congregational singing; and some will be the musical domain of the group alone.

In addition to the music itself, this book also seeks to provide some of the corresponding spiritual and textual background required to interpret the music in a prayerful way. Thus each piece features its own “Companion Page” which includes:

The traditional Hebrew text

Page numbers for the text in a number of Jewish prayerbooks

English translations from the Rabbinical Assembly's new Siddur Lev Shalem (used with permission)

“KavaNotes” which include my own guidance on how to feel & understand the prayer text, together with practical suggestions on how to best utilize the music in both traditional and flexible worship contexts

“From the Composer/Arranger” – personal notes from the composers and arrangers themselves that give insight into how the piece was conceived, how to sing it, and what it means to the arranger themselves

Poetic readings from Siddur Lev Shalem

The opening chapter, entitled “From Performance to Prayer: Cultivating Spirituality in A Cappella” (also available online) contains thoughts from current Jewish music leaders on how a cappella music might best be used in prayer. I am indebted to Joey Weisenberg, Cantor Rosalie Boxt, Dr. Joshua Jacobson, Hazzan David Tilman, and Rabbi Ruth Gan Kagan, Daphna Rosenberg, and Yoel Sykes of Nava Tehila for all sharing their experience as worship leaders and their very diverse opinions on if and how a cappella music might be channeled into holy service. I sincerely hope that this book will help support established synagogues, emergent communities, Hillels, summer camps, day schools, and singing Jews everywhere that are inspired to start and develop a new a cappella group.

In Jewish thought, the beautiful is not always synonymous with the good. It is our tikkun – our refining of the world – to take the beautiful and direct it towards the good. This is the sacred mission of cantors in bringing musical artistry to prayer, and I hope this book will contribute to this holy and beautiful work. Thousands of a cappella-loving people have found their soul's song in this genre.

So too has God given each of us unique potentials for feeling, growth, healing, and community that can only be realized through music. May that which is joyful and beautiful also help point to that which is holy within us, and beyond us, that which is truly good. May God bless anyone who seeks to take their love and gifts in a cappella and channel them towards prayer.

In the development of a genre, one can tell its level of reception by the emergence of parody. We can recognize this stage in Jewish a cappella's own journey through a recent Hanukkah video parody of Toto's “Africa” (produced by professional Jewish a cappella group, Shir Soul). This YouTube hit shows the great extent to which North American Jews have come to expect a cappella music videos as part of their Jewish lives.

“Soup of the Day” in Hebrew. The group was founded in 2003 by high school-aged brothers Micah & Reuben Hendler, both exceptional musicians and the producers of many of the group's first arrangements. Both went on to sing in the Whiffenpoofs, an elite all-male a cappella group at Yale University. Additionally, Micah's experience in Peace Studies and a cappella led him to found the Jerusalem Youth Chorus (www.jerusalemyouthchorus.org), a Jerusalem-based ensemble of high-school aged Jews, Israeli Arabs, Muslims, and Christians that both sing together and model dialogue about Middle east conflict. The JYC has toured the world and performed with dozens of celebrity artists, spreading its message of encounter and peace. Micah is the arranger of the final piece of this book ( “Adon Olam”). His mother, Deborah (the first behind-the-scenes steward of the group), is reliably and deservedly bursting with naches for her successful and musical children.

The de-hierarchicalization of God and its concomitant effects on the embodied leadership models of prayer in American synagogues cannot be underemphasized. Sociopetal (circle-based) re-orientations of prayer spaces, the use of niggun, chant, and congregational melody, and more humble uses of vocal and musical leadership all point to a return to the community itself as a renewed focus and vital center of worship and connection.

This is not to say that the congregation did not participate in the pre-niggunified synagogue. The congregational murmerei, the hum of the traditional words of the prayerbook, mumbled and invoked with trance-like zest and fervor, was the classic participation of the worshiper in the traditional synagogue, together with (albeit less) expected moments of congregational singing. Cantor Samuel Rosenbaum z"l, the second Executive Vice-President of the Cantors Assembly, presciently observed the loss of this prayer knowledge and the deepening chasm of congregational silence that would lead to the abandoning of many choral and soloistic worship forms for a growing reliance on congregational melodies:

“More and more we miss the reassuring hum of a congregation davening; the comforting continuum of the Dave we’d murmerei. We hear, less and less, the natural, unrestrained praying sounds which daveners create as they bite into a new tefillah with a will. The silence which now follows the conclusion of the Cantor's chant, or of a choral piece, grows more deafening and disturbing.

You must understand that what charges a piece of vocal music with spiritual significance, what changes an aria into a prayer, what stokes the spiritual fires of the Hazzan and the congregant alike, is the instinctive and instructive feedback which each gives to the other. For the Hazzan, whose task it is to help the Jew to achieve union with the great Listening Ear, with the shome'ah tefillah, it means that he has made contact. With whom? With God? With the worshipper? With both? Only God knows for sure. At the very least, it means he has touched those who have appointed him their sheliah tzibbur, their emissary in prayer.”

(From “Towards a New Vision of Hazzanut,” 1989. Published in Tefillat Shmuel: Selected Writings of Hazzan Samuel Rosenbaum. Ed. Matthew Austerklein. Cantors Assembly: 2018).

Cf. Mishnah Avot 2:4.

I am indebted to Cantor Shmuel Barzilai and the choir of the Viennese Stadttempel for first modeling tome how musically “alive” a m'shorr'im choir could be while I was a music student in Austria in 2006.

There are some notable, if limited exceptions to this rule. One might expect improvised a cappella harmonies from professional groups that are invited to synagogues to lead worship in addition to concertizing. Two synagogues, to my knowledge, do regularly employ liturgical a cappella at a high level. Both are located in Toronto, and feature many alumni of the University of Toronto Jewish a cappella group, Varsity Jews.

The closest model to this is that pioneered by Joey Weisenberg, who typically engages an inner circle of musically and liturgically sensitive people to form his “spontaneous choir,” whose energy and kavannah.

ah yasher koach

This sounds really exciting! Is there a way to listen to some of the arrangements or see a sample page or two before committing to buying the book? I'd want to see if my choristers are up for the challenge...