I remember my first feeling of discovery as an academic, reading an antiquated source with staggering resonance for the present day. Over a decade ago, long before its tent cities and anti-Semitic ignominy, I walked a few blocks south from my graduate school to Columbia University’s Butler Library to visit its Rare Book Room. Herein lay a readily available copy of a three-hundred year old defense of cantors.

At first I could hardly believe that they would let me handle its ancient and gossamer pages. But when I began to read and transcribe its contents, my mind was blown. With each successive line, I became more and more astonished as the little booklet revealed the world of the early eighteenth century in which the Ashkenazi cantorate became self-aware, articulating the religious stakes of its musical vocation and defending itself from the oldest of anti-cantor accusations: ignorance, impiety, and musical egotism.

The feeling was electrifying, like I was reading breaking news that had been hidden away for me three centuries ago.

Thank you for reading Beyond the Music! If you enjoy reading this newsletter, please consider supporting me with a paid subscription.

Every field has these moments. The rabbi-academic Solomon Schechter famously experienced one when two Scottish Presbyterian sisters at Westminster College in Cambridge handed him the above Hebrew fragment of the Wisdom of Ben Sirach. Schechter had long contended against the force of his Cambridge colleagues that this apocryphal book, whose contents were only known in Greek, were originally composed in Hebrew. Electrified by the validation of his years of research and with the promise of untold scholarly riches, Schechter led the charge for the acquisition of what is now known as the Cairo Geniza - a collection which changed the face of Jewish scholarship and continues to do so to this day.

I can only imagine Schechter’s brimming excitement when he first saw that dusty Hebrew parchment. Last Tuesday, that same feeling came for me.

The Bodleian Library in Oxford is the home of the Oppenheim Collection — one of the world’s richest collections of early modern Jewish books and manuscripts. They were amassed by Rabbi David Oppenheim (1664-1736), the famous Chief Rabbi of Nikolsburg & Prague and consummate book collector. Oppenheim’s volumes feature heavily in my doctoral work, as they include a number of books and songs which are related to the early modern cantorate. But a few months ago, I realized that I had given ample attention to the catalog of his books yet not adequately explored the manuscripts. After a stellar find sent to me by my colleague and expert in early modern Jewish literary culture, Dr. Olga Sixtová, I made another search and came across an entry for a curious manuscript — נגינת דוד (“David’s Music”), which contained “advice” for cantors.

In the synagogue as in scholarship, “advice” is usually a code word for fiery criticism. As we will see, “David’s Music” did not disappoint.

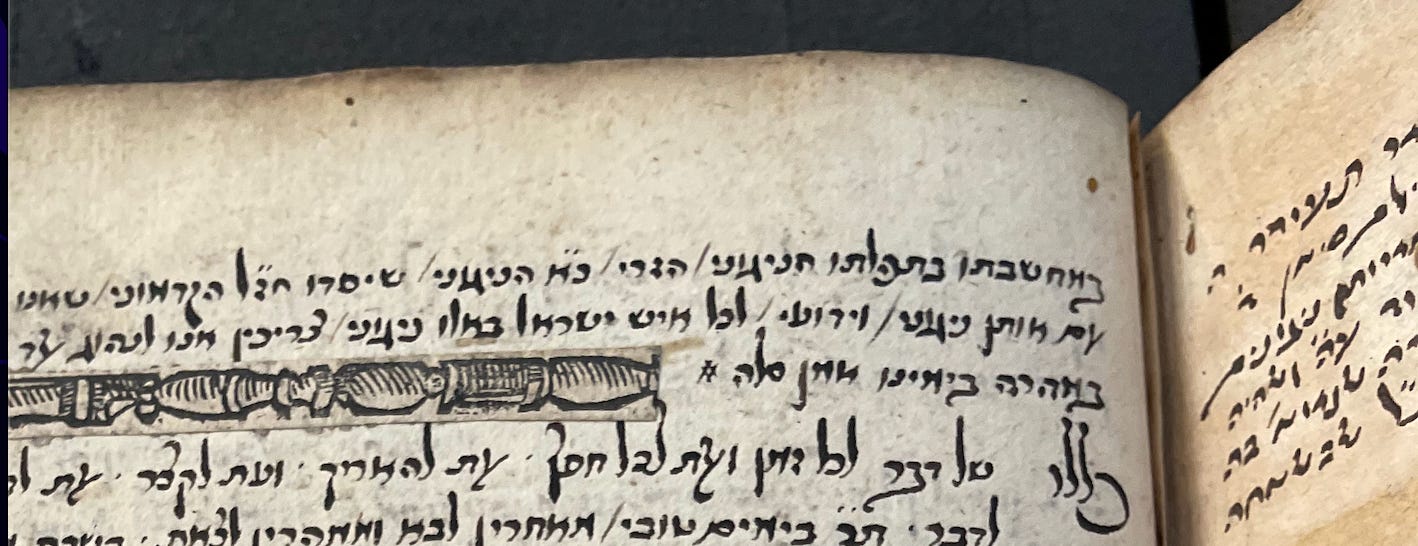

According to the catalog, this cantorial advice came at the end of a larger manuscript by Rabbi David b. Menachem Ulma, who by all accounts was a Bohemian rabbi (from a long line of Prague Jews) who died in 1635.1 While my analysis is currently limited (I have only seen the cantor-related end of the manuscript, not the beginning), the source strongly suggests a Czech origin. This is substantiated by the author, the contents, and the manuscript’s interesting woodcuts and graphic elements pasted into the volume to give aesthetic form to a future printed version, including the title page of a Czech calendar (c. 1606 - my thanks to Dr. Daniel Soukup for identifying this).

So what makes this early seventeenth century manuscript so powerful?

The answer is that Rabbi Ulma appears to have been not just a serious kabbalist, but a reformed klezmer musician providing guidance to cantors about how to preserve old, traditional melodies and avoid the temptations of bringing music from the nations, and from the klezmer bands, into the time-sensitive and religiously distinct world of the synagogue. His testimony represents perhaps the most colorful and detailed evidence to date concerning early modern klezmer musicianship and cantorial music.

Klezmer history prior to the eighteenth century is very scant; what we do know is that Prague’s Jewish musicians were already well-known for their skill in the sixteenth century, and in the early seventeenth century were able to incorporate as a musician’s guild — the klezmer guild. As professional musicians, they successfully received privileges from the Hapsburgs to play music for the full gamut of Christian religious services and feasts, much to the chagrin of Christian musicians in the city.2 Rabbi Ulma himself recounts his own experience at one such event, described in my rough translation below:

“From early days I was often in the company of respected and important princes, dukes and great authorities, with my musical instruments [and] with a band of distinguished klezmorim [עם חברותה כלי זמרים חשובים] …when I saw there a number of great and very important princes, and there were there a number of ensembles [כתות] of non-Jewish instrumentalists who had among them great artists that would also play before them distinguished, stirring, and highly glorified melodies. Thus I trembled and I was fearful and overwhelmed [together] with my friend (of blessed memory), and we were at the end of our rope as to what to do. And I set my mind to search out and seek after distinguished melodies [ניגונים חשובים], such as they enjoyed and desired, and not those melodies that [we] regularly play to get people to dance, or to play at feasts before drunk and distempered thieves.

Here we have a klezmer thrust into the courts of Bohemian nobility, entranced and even embarrassed by the grandeur of the melodies of non-Jewish ensembles — referred to him earlier in the manuscript as “the wisdom of the nations that is called ‘music’ [מוזג].”3 This stood to him in contrast to the dance music and street music for which his klezmorim were well-known.

But don’t take Rabbi Ulma for a grass-is-greener kind of Jewish musician. He is a staunch defender of traditional synagogue music, adjuring cantors to use the “old, familiar melodies” which are taught from one’s youth and enable one to pray. He is even the first Jewish writer that I have seen, centuries in advance of our modern cantorial apologists, to claim that the ָAshkenazic melodies of the High Holidays were set down in pre-medieval Jewish antiquity.4

But what is most striking is R. Ulma’s explicit description of how the cantors of his era have transported the soundscape of the dance-music klezmorim into the vocal stylings of the synagogue:

“And now, in place of those beautiful melodies — old, pleasant, and very good ones which were our ancestors’ heritage [מוסר], as I explained –- the cantors have switched things up, changing a portion and making melodies in the synagogue with their mouth which the klezmorim regularly play on the flute to make [people] join in the dances. For at festive meals when [the guests] recline for a spell, then the klezmorim regularly make dances with drum and lyre, on flute and lute, with cymbals and trumpets (known as schalmei, or trometen as they are called) such melodies known in Yiddish [as] “Berin Tanz,” “Hop Recht, ”and the like.5 They make a number of insane melodies [ניגונים משוגעים], humming to the tune of the lute,6 considered like David [himself]. They think that their instruments are like David’s instruments, that they are for the Heavens, yet they are actually for pleasure.”

This source spells out in explicit terms what late seventeenth century and early eighteenth century sources only suggest — that Ashkenazi cantors, not unlike Moroccan and Turkish ones in future generations, are mimicking instrumental genres with their voices.7 And it confirms Idelsohn’s century-old suggestion that the klezmorim were the teachers of cantors in the ways of music.8 This source further represents, I believe, the earliest mentions of specific dance melodies in the original Prague klezmer repertoire.9

R. Ulma spends many pages railing at such innovations, which import the musical and emotional explosivity of festive meals and dances to the pious, liturgical, and spiritual tight-rope act of Jewish religious services. This crossover creates many halachic and kabbalistic problems which are familiar from cantorial history, but this source appears to predates most articulations of these issues by almost a full century.

While I have shared some initial findings above, there is a lot more work ahead. I have translated about 60% of the document, but this is a first attempt and requires expansion and much more analysis. The date and provenance too need to be more thoroughly confirmed. And there remains the very real mystery of a distinctive change in hand and paper in the last several pages (shown above)— discontinuous with the language of the older page yet with no change in subject or theme.

A source like this fascinating, but not only because it is academic. Discoveries like this one illuminate the origins of the musical forms we know today and dynamics of Jewish creativity. They also reveal the multiple worlds in which musicians often find themselves, as well as the religious tensions that they face.

“David’s Music” has only begun to reveal its secrets, and I am excited for what is ahead.

But I am most excited because I get to share it with you.

What questions would you ask of this source?

How does this change your understanding of Jewish music?

Who should be studying this?

Drop me a line at mattausterklein@substack.com, or leave your thoughts in the comments below.

There is one other David Ulma listed in Hock’s guide to Jewish epitaphs in Prague. This second David Ulma (d. 1713) is listed as the Primas, or Mayor of the Jewish community. Since the manuscript indicates a rabbinic writer, this seems a much less likely candidate for the R. David Ulma of Neginat David.

The Christian musicians guild in Prague formally petitioned the Archbishop to revoke their priviliges, arguing that the klezmorim were flooding the market and lowering the quality of music in the city. Their petitions were rejected. See the German sources quoted in Walter Salmen, “--denn die Fiedel macht das Fest”: Jüdische Jüdische Musikanten und Tänzer vom 13. bis 20. Jahrhundert (Innsbruck: Edition Hebling, 1991): 157-165.

The spelling of this term with a gimel [ג] rather than the Italianate “musika” [מוסיקה/מוסיקא] further suggests this source is based in Prague. The only other instance I can find of this spelling is in the Prague-published unicum, תוכחה לחזנים –“Rebuke of Cantors” (Opp. 8o 1073): “ראו חכמת ה׳׳מוזיג איך וצריך לימוד.”

“בלתי ספק שיסדו אות׳ התאני׳ והמוראי׳ בפרט הניגוני׳ של ימים נוראים”. Rabbi Ulma’s characterization of set muisc echoes the conservatism of the Maharil (1365-1427), further confirming the set of a core repertoire of traditional prayer melodies that were already standard in East-Central Europe by the seventeeth century. In contrast to the morde modern appelation of the oldest stratum of these melodies as misinai (literally “from Sinai)”, R. Ulma’s unique formulation uniquely points to the rabbinic progenitors of the oral law [תושב׳׳ע].

בערין טנץ הוף רעכט וכיוצא בזה

For observations about the adaptation of instrumental repertoires in synagogue vocal music across Turkish, Moroccan, and Ashkenazic sources, see Edwin Seroussi, “The Pesrev as a Vocal Genre in Ottoman Hebrew Sources,” Turkish Quarterly Review 4, No. 3 (1991): 1n5.

Abraham Zvi Idelsohn, Jewish Music in its Historical Development (New York: Tudor, 1948): 207.

Another important part of this source is its ample observation of the klezmorim’s use of trumpets in the performance of dance repertoire and street music. These instruments are evident in parades of the Prague Jewish community dating to at least 1678, but their presence in klezmer ensembles is not otherwise well-documented. See for example Opp. 215, 125v:

And now, all the more so in the synagogue the service, which is prayer, should be with reverence, and the cantors should rejoice with trembling, [with] the old, appropriate and pleasant melodies which belong to the prayer of the synagogue, and not melodies which belong to joy alone, in order to dance by them, which are regularly performed on horns and cymbals, called feld-trometen (“field trumpets”) in Yiddish..

As much as a witness of cantorial history, this source’s many descriptions of klezmorim may make a potentially seismic impact in our understanding of early klezmer history.

Berin Tanz, Hop recht - bring to mind the Story of The Shpoler Zeide - Hop Kozak.

Was the Berin Tanz considered a typical Jewish dance?

Also would it be plausible to say that the Berin Tanz and Hop Recht is in fact one act, perhaps Hop Recht is the song accompaniyng the Berin Tanz?

Now we have Camp songs, the Beatles music and Broadway tunes that have become part of our synagogue musical experience. Is this something that has always happened? It would be interesting to trace this in other times.