Cantor Cellophane

A New Lament for Cantorial Invisibility

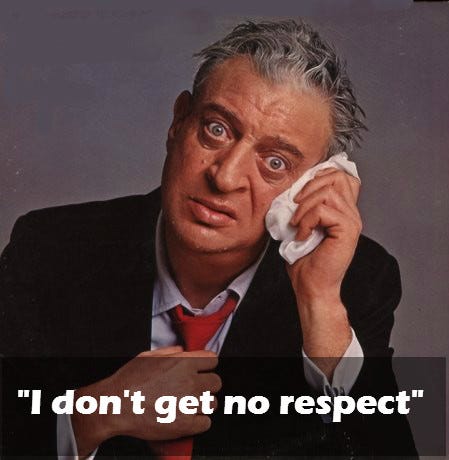

This week, the online cantorial community erupted.

Not with a prayer or song. With a cathartic, full-throated lament.

Someone had spoken aloud one of the quiet burdens of cantorial life — invisibility.

I learned very quickly in cantorial school that, despite choosing an outward-facing clerical vocation, cantors were often invisible Jewish leaders. Special funding, sponsored training, and other exclusive professional opportunities were generously available to future rabbis. Their culture and success were front and center as the face of our seminary.

This alone was a very good thing; I wanted my rabbinic colleagues, then as now, to have those opportunities and to succeed. But being part of the cantorial community required, as the Sheryl Sandberg famously put it, leaning in. Such fellowships, training, and glitzy opportunities did not naturally come across our desks. We had to keep our ear to the ground and to fiercely advocate for ourselves. Both at the macroagressive and microagressive levels, being a cantor was like being the Esau of Jewish clergy — dumbfounded, left out, begging for a blessing.

I don’t feel this way at all in my new community — I have awesome colleagues and work at a great shul.

But it is an experience that nearly all modern cantors have.

This week, Cantor Vladimir Lapin gave voice to this perennial cantorial problem in his widely-shared article, “The Hidden Cantor: Why members of our clergy are missing from the picture.” Observing a recent major survey on “The Future of Rabbinic Leadership,” Cantor Lapin again noted the neglect of the cantorate in studies and conversations on the future of Jewish life.

Lapin’s lucid prose speaks for itself:

“Cantors often live in the blind spots of Jewish institutional life. We are central to the work, yet absent from the language that describes it. In my daily life as a cantor at a large congregation in the suburbs of Cleveland, I lead prayer, teach Torah, officiate at weddings, funerals, baby namings and unveilings. I sit with families in crisis. I learn the stories of people who have returned to shul after long absences. I prepare nervous thirteen-year-olds for b’nei mitzvah and help adults sound out their first alef bet. I hold a community’s music, memory and emotion, often in the same service. None of this is unusual. It is simply what cantors do. And there are a lot of us.”

The “blind spots” that Cantor Lapin describes perfectly encapsulate the cantor’s position in the synagogue care economy. Like those similarly-situated professions of nurses, teachers, caregivers, and even parents, cantors perform essential services at the heart of Jewish flourishing. Yet such activities are less quantifiable as “leadership” in its modern, executive sense. They do not inherently create “innovation” — as the prophet does in God’s name. Rather, like the biblical priest, they serve the families before them with the current resources of faith and tradition.

This stands in contrast to the economy of professional fellowships into which much rabbinic leadership is socialized. Some provide deep learning and new insights (I have, baruch hashem, found my way into a few of these). Yet the fellowship economy can also itself be a form of public performance, offering rabbis a degree of digitally-shareable street cred as the innovative leaders of the future — leaders that, together with cantors, we truly need them to be.

The cantor is thus the most underleveraged group of synagogue professionals in American Jewish life. If we put into this group of musical Jewish clergy even a fraction of the investment and professional development that we rightly put into the rabbinate, we would immeasurably strengthen our institutions and synagogues.

Surveying the 1,100+ cantors of the Cantors Assembly and American Conference of Cantors, Lapin notes:

“We are not a quirky side note. We are a large, organized, professional clergy body. Many of us are fully ordained, with graduate level training in liturgy, education, pastoral care and Jewish text. We do not simply “sing the services.” We create the spiritual arc of prayer, shape communal ritual, teach at every age level and show up whenever people are most vulnerable. Cantors are not assistants. We are not musical accessories to rabbinic leadership. We are clergy. Fully trained. Deeply formed. Called to serve.”

Cantor Lapin is especially correct about our call to serve. Almost all cantors work in synagogues and are tied to their success. This is in contrast to the research which Cantor Lapin cites, indicating that just slightly over half of non-orthodox rabbis pursue pulpit positions. Thus many unfilled rabbinic pulpits are sent to cantorial placement organizations each year. Synagogues have regularly begun to seek “a second clergy” — not just because of the breakdown of traditional roles, but because they need to cast a wide net in a tough market. Yet fidelity to shuls is why over 12% of Cantors Assembly members have obtained a rabbinic ordination, with more and more each year looking towards the rabbinate as a mid-career pivot.

Lapin beautifully portrays this quiet cantorial loyalty to the synagogue: “I am here. My colleagues are here. We have always been here.”

There are two central aspects of Cantor Lapin’s article that deserve attention. The first is weak representation of cantors as “real clergy.” This is a deep issue for another article, and one which strikes at the very heart of the cantorate and cantors. But the second, is the objective lack of adequate attention to the cantorate’s professional state of affairs.1 The “cantorial pipeline” too has experienced major changes over the past several decades: whereas once classically-trained singers and former synagogue choristers made up the lion’s share of cantorial students, now they increasingly come from backgrounds in Jewish a cappella, Jewish summer camp, and non-classical music. Furthermore, the cantorial pipeline, while diminished, has not waned to the same degree as the rabbinic one. This notion should encourage us to see the rabbinate and cantorate as complementary professions which often attract different types of Jews — together contributing to the aggregate klei kodesh staffing of the American synagogue.

Like the care economy, the cantorate is doing essential work in the American Jewish communities— even as many of our institutions, as yet, remain scientifically uncurious (at best) as to its quantifiable contributions and evolution. A complementary cantorial study to the Atra survey might yield similarly helpful results.

To give Cantor Lapin the last word:

“It is time for the hidden cantor to be seen, counted and taken seriously as clergy. When that happens, our understanding of Jewish leadership will not only be more accurate; it will be more whole.”

The cantorate is not only hidden/ignored in Jewish leadership surveys. The earliest cantorial journal in 1848 complained about how it had been thoroughly ignored by Wissenschaft des Judentums —a typical fate for music in academia, which is often seen as an oddball or “not serious” field. My doctoral advisor, Edwin Seroussi, once described Jewish Music as “The ‘Jew’ of Jewish Studies.” To my mind, the cantorate is thus “The Jew of the Jew of Jewish Studies” — the ultimate in esoterica whose invisible sounds cannot be divined by the text-worshipping scholar. A variant of this may be at play in our current predicament.

I think that in any work or professional calling you have to be your own publicist, your own connection to congregants and the public, and greater communities. Nothing stops a cantor from being involved outside the synagogue which is essential for recognition within the congregation's synagogue or Temple and its desirable. Years ago Cantor David Lefkowitz produced a film called 'The Cantor-More than a Singer.' So how do we answer that challenge? Cantor/Clergy, Cantor/Educator, Cantor/Rabbi...For me it was providing meaningful services, with special services several times a year. I developed a Monthly Friday evening rotation of a Classic Service , a Renewal type service modeled on BJ in NYC, A Youth Choir Service, and a creative new Jewish Music Service. Congregants made their own choices for the familiar or the new. Youth Choir services brought families and gave children the experience of being part of a service and not an 'audience'. Publicizing these services was another part of their effectiveness, although there was the congregant who said 'we're tired of reading about the Youth Choir.' Another congregant reading the same newsletter was Justice Arthur Goldberg who told me I was the most dedicated person he had ever met in Washington, DC.

On visits to the Hebrew Home or Hospitals, I learned to listen and earned some credits towards chaplaincy. I always left my Rabbinic/Cantorial card so that family would know I had visited and could contact me if necessary, which they did.

I was part of the staff meetings and learned to be there on time. And I insisted on being able to occasionally be at Executive Meetings and Board Meetings so that I could speak up about our work, and be aware of the congregation's concerns or plans. I made prior requests that I wanted to be part of the agenda.

When building renewal was in progress, I wrote to the builder to express my needs for my office and rehearsal space, as well as the needs for space in the choir loft including emergency safety for the singers. Yes, the builder responded in writing.

In teaching I was able to have trope classes in addition to teaching students individually. Some cantors avoid this, but I think that is a mistake, for that is when you get to know your congregants. The trope classes at grade 6 and grade 7 made the concept of trope familiar when lessons began.

Yes, I sang the anthems at sisterhood and men's club meetings. I organized groups to demonstrate at the Soviet Embassy, and visited the nursery school with a Torah, as well as special music programs for the young.

You need the synagogue staff to assist you in your P/R. No one can say it better than you, no one cares more than you. For large programs I brought together marketing professionals from the congregation for a meeting where an outline was given to them and we had quick back and forth about budgets, Press Release, contacts. These were invaluable.

Also for those who have a daily minyan, that is a lifeline for many to the synagogue.

The question really is: Are you invisible to your family? How do you do these things and have a semblance of balance with your life outside the synagogue?

I retired from the cantorate over 22 years ago and I'm still visible. You can do it!

Rabbi/Cantor Arnold Saltzman since 2008