What do cantors mean in movies?

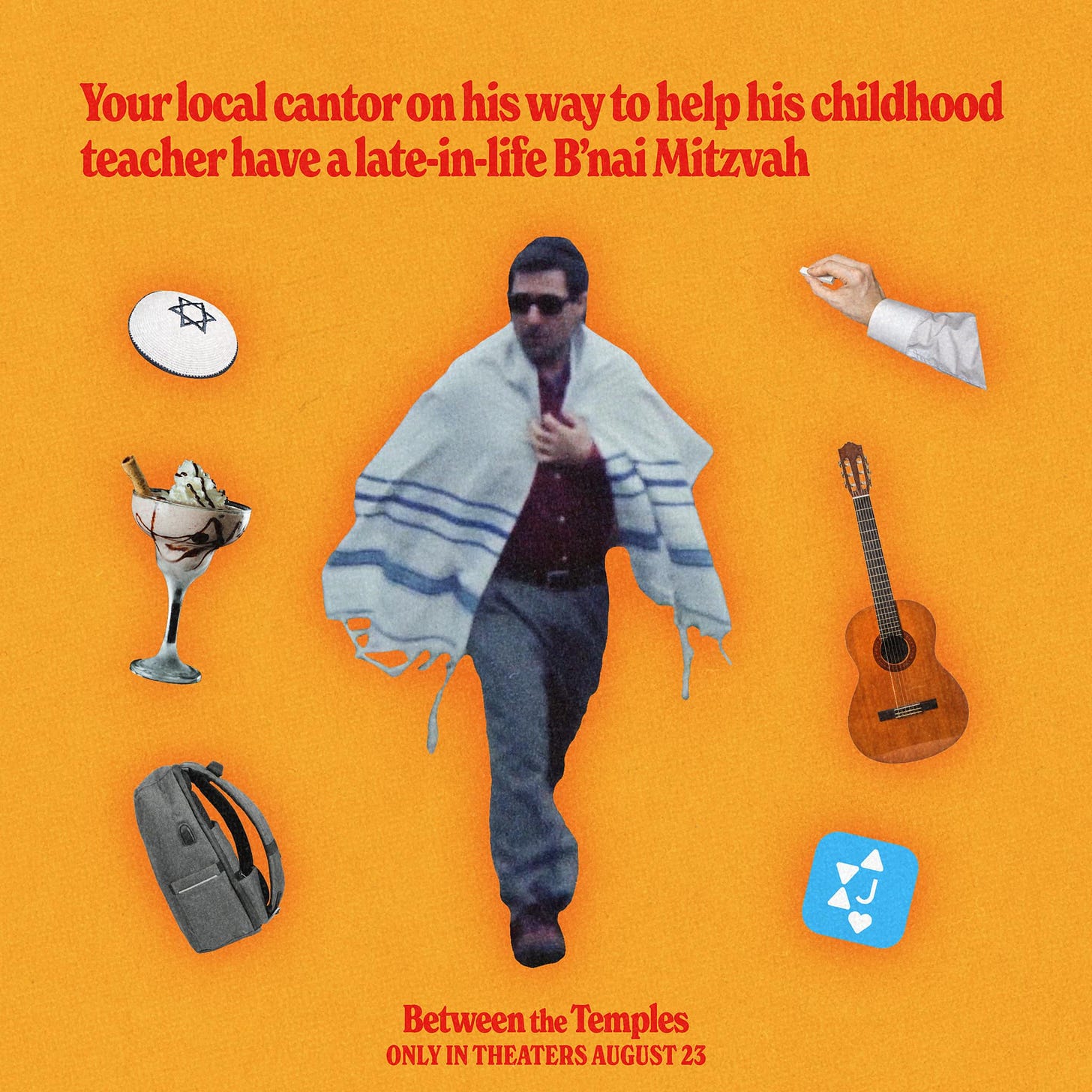

With this past weekend’s release of Nathan Silver’s new film, Between the Temples, I thought it was time to find out.

I polled my colleagues and compiled a list of all of the cantorial characters I could find. You can see it for yourself here (If I missed any, please drop me a note or let me know in the comments).

As for Between the Temples — the film follows a cantor, Ben Gottlieb, who finds himself listless and unable to sing after the tragic loss of his wife. He is gradually lifted up out of his depression by rekindling a friendship with his childhood music teacher, Carla O’Connor (née Kessler), who asks him to give her an adult bat mitzvah. The movie follows Ben’s reclaiming of himself and the meaning of his life through his relationship with Carla amidst the difficulty of grief and communal (and family) expectations.

It is complex and well-done film, if sometimes odd and painful. Yet to convey its full message and impact, let’s consider it in light of a century of cinematic cantors.

Thank you for reading Beyond the Music! If you enjoy reading this newsletter, please consider supporting me with a paid subscription.

I. A Century of Cantors in Cinema

Cantors have been part of American cinema since its inception — literally, cantors were the subject of the very first “talking picture.” The Jazz Singer (1927), starring Al Jolson, tells the story of young Jake Rabinowitz, a cantor’s son, who is torn between his pious Jewish family and his emerging success as a vaudeville performer. Thus the modern era of American film began with a classic articulation of the cantor’s dilemma: whether to choose expression (the stage) or limitation (the religious life / the cantorate). The film concludes with reconciliation; the older Jake (now the singer “Jack Robin”) succeeds his dying father as the cantor for Kol Nidre, while his mother recognizes that her son can have faith and also perform — "a jazz singer, singing to his God."

This struggle of the prayer leader and the artist was a classic issue for cantors, particularly in the wake of the cultural stardom of the Golden Age of Hazzanut. And it comes down to us today, as remarked by Israeli director, Joseph Cedar:

"There is that contradiction in every Cantor between someone who's job it is to mediate between the congregation and God, but who's also a performer. Those two functions don't always live with each other harmoniously. That's a great conflict. I like Cantors. They are torn by these two sides."

Most cantors in American film, however, were not the stars of the show. With only a few exceptions, which I will detail later, I would argue that cantors largely play the role of sacred furniture — minor extra characters who are part of the musical backdrop of a religious scene.

These sacred furniture roles include many scenes of synagogue services, most of which feature the cantorial roles played by actual cantors. Examples include Cantor Matt Axelrod in The Plot Against America (2020), Cantor Bob Abelson in Those People (2015), and Cantor Rafi Frieder in Keeping the Faith (2005). All three of these cantorial cameos set the musical mood for a liturgical scene.

Although I have to give a special shout out to Cantor Frieder for calling page numbers instead of his rabbi, Ben Stiller.

One of the earliest and most revealing iterations of the cinematic furniture cantor is in the psychedelic comedy, I Love You, Alice B. Toklas (1968). Here, Cantor Samuel "Shmulik" Kelemer and his brother, Beryl, played the “twin cantors” employed for the wedding of the protagonist, Harold Fine, and his fiancée, Joyce.1 The couple discuss them in a humorous way, showing these cantors as objects rather than subjects in the drama:

Joyce: That's, ah, twin cantors.

Harold: They're really twins?

Joyce : Oh yes. Now Harold, they're very expensive, but they perform the most beautiful ceremony.

Harold: Hmm. Are they fraternal or identical?

Joyce: Well, they're not... identical. No, I don’t think that they are. I'm just doing it for my father, you see, I…I felt that that's the least that we could do…. I feel that you really don’t want them. Now, if you don't want them, I want you to tell me that.

Harold: The very thought of cantors in stereo, instead of mono cantor, appeals to me.

Joyce: Oh, Harold…

The minor cantors of I Love You, Alice B. Toklas nevertheless serve an important symbolic role. These expensive and robe-clad chazonim represent the respectable path of married suburban life — one which the protagonist longs to abandon for the alternative hippie scene of sex, drugs, and rock-and-roll.

By the swinging sixties, the cantor could be depicted on screen as a figure of domesticity — “the Man” in Jewish musical form. This is a far cry from the cantor-performer dilemmas of the first half of the twentieth century, when cantors were more easily identifiable as edgy artists. And it is that aura of respectability which will be much more familiar to the sleepy, upstate-New-York environs of Between the Temples.

Before turning to Nathan Silver’s one-night wonder, let’s take a look at one more poignant scene in the history of cantorial cameos in which the chazonus actually comments on the film.

Norman: The Moderate Rise and Tragic Fall of a New York Fixer (2016), starring Richard Gere, is the story of a hapless political operator who gets involved in a grand series of events after befriending a charismatic Israeli politician. As the main character realizes the ultimate futility of his schemes, the film’s chazonus soundtrack serves a subtle form of Greek chorus. Over the course of several scenes, Cantor Azi Schwartz and his choir beautifully chant a setting of the mi shebeirach liturgy for the congregation, which focuses on blessing those who sustain the community’s needs. Through the bittersweet sounds of the chazonus, we find a sonic mirror of the bitter tragedy of the Norman, who aspires to be among the “sustainers” of the community but who ultimately comes out with more curses than blessings.

From cantors in the background, let’s move to movies with cantors in the foreground.

Movies with cantorial protagonists are few and far between, including (by my count) just four in the last century: The Jazz Singer (1927, with its two remakes in 1952 and 1980); Singing in the Dark (1958), To Dust (2018), and this weekend’s Between the Temples (2024).

These cantor-flicks flock together around two themes. The early pair of films deal with the familiar religious tension between artist and prayer leader. Singing in the Dark (starring the famous Yiddish-actor-turned-hazzan, Moshe Oysher) tells the tale of an amnesiac Holocaust survivor who becomes a showbiz headliner, but only through the intervention of psychiatry and a freak accident does he remember his cantorial past. Like The Jazz Singer before it, the movie highlights the protagonist’s theatrical and vocal abilities to explore the duality of Jewish-American identity in the realm of music.

The more recent films, curiously, both deal with cantors in upstate New York mourning the deaths of their wives.2 To Dust (2018) features a cantorial protagonist, Shmuel, who is haunted by the death of his wife and the part of rabbinic thought holds that the soul is not fully at peace until the body decomposes. Unsatisfied with religious and familial counsel, Shmuel turns to a local biology professor (played by Matthew Broderick) to help him understand death. Like in Between the Temples, the main character’s religious life is a leaky container for his existential disorientation.

More to the point, the cantorate in these modern movies is a prism for a unique human difficulty — the pain of being a symbol of meaning when you are searching for meaning yourself.

II. When Symbols Search for Meaning: Between the Temples

Victor Frankl’s famous book, Man’s Search For Meaning, explored how human beings can find transcendent purpose which allows them to survive even the most dire of conditions. Forged through his horrifying experience in the Auschwitz concentration camp, the book is a testament to human resilience through which those with meaning— from the traditionally transmitted to the incredibly personal — can rise above difficulty.

This is what a life of commitment and faith is about. Such belief and purpose does not inevitably protect a person from suffering, but rather offers them the tools and relationships to transcend it.

Between the Temples is a movie about tragedy when such tools are difficult to find. Crushed into a depressive funk by his wife’s death, we meet Cantor Ben (played by Jason Schwartzman) at a low point, unable to sing. This is not helped by his comically overbearing mom (one of two), a successful real estate agent and major donor to the synagogue who keeps trying to set him up with ill-fitting partners.

Ben’s co-worker Rabbi Bruce, played by the SNL veteran writer Robert Smigel, is almost without religious pretense, practicing his golf putt into a shofar and tells dirty jokes at a Holocaust Torah fundraiser.3 Smigel’s Bruce could have gone to rabbinical school with the three rabbis of another cantor-related film, A Serious Man (2009). The Rabbi is not without merits —he is a friend and colleague, and supports his cantor in being able to continue in his job. But his, like the Serious Man rabbis, is a ministry with little religious wisdom to offer.

“The purpose of a cantor is to sing,” Ben states as he reflects on his lack of voice and purpose. This too shows theological black hole that pulls at the Jewish matter of the film. The purpose of a cantor is not to sing — it is to pray. That is why the cantor is the shaliach tzibbur — the congregation’s messenger in praying to God. Between the Temples thus points to a Jewish world where personal or interpersonal meaning are the only ones to be found. In such a post-religious world, it is just me and you.4

Yet in that interpersonal realm the film does succeed in being a meaningful (if awkward) journey of care. Ben’s bat mitzvah student and former music teacher, wonderfully played by Carol Kane, reminds her own former student what mutual kindness looks like. Her genuine care for him, muddled as it may be with a suppressed romantic connection, is reflected in the reading that she learns and recites for her adult bat mitzvah (Leviticus 19:15-18):

לֹא־תַעֲשׂ֥וּ עָ֙וֶל֙ בַּמִּשְׁפָּ֔ט לֹא־תִשָּׂ֣א פְנֵי־דָ֔ל וְלֹ֥א תֶהְדַּ֖ר פְּנֵ֣י גָד֑וֹל בְּצֶ֖דֶק תִּשְׁפֹּ֥ט עֲמִיתֶֽךָ׃ לֹא־תֵלֵ֤ךְ רָכִיל֙ בְּעַמֶּ֔יךָ לֹ֥א תַעֲמֹ֖ד עַל־דַּ֣ם רֵעֶ֑ךָ אֲנִ֖י ה׳׃ לֹֽא־תִשְׂנָ֥א אֶת־אָחִ֖יךָ בִּלְבָבֶ֑ךָ הוֹכֵ֤חַ תּוֹכִ֙יחַ֙ אֶת־עֲמִיתֶ֔ךָ וְלֹא־תִשָּׂ֥א עָלָ֖יו חֵֽטְא׃ לֹֽא־תִקֹּ֤ם וְלֹֽא־תִטֹּר֙ אֶת־בְּנֵ֣י עַמֶּ֔ךָ וְאָֽהַבְתָּ֥ לְרֵעֲךָ֖ כָּמ֑וֹךָ אֲנִ֖י ה׳׃ You shall not render an unfair decision: do not favor the poor or show deference to the rich; judge your kin fairly. Do not deal basely with members of your people. Do not profit by the blood of your neighbor: I am the Lord. You shall not hate your kinsfolk in your heart. Reprove your kin but incur no guilt on their account. You shall not take vengeance or bear a grudge against members of your people. Love your neighbor as yourself: I am the Lord.

These ethics, which come at the middle of the entire Torah, cut through Carla’s quirky but determined learning and friendship with Ben. She, in many senses of the word, is the epitome of “loving your neighbor as yourself.”

This awkward romanticism harkens back to another strange film which eerily illuminates movie from fifty years ago — Harold and Maude (1971).

Harold and Maude is a dark comedy about a death-obsessed teenager who stages outlandish fake suicide attempts in order to gain his parents attention (the parents, respectable society types, are unmoved by his antics). Yet Harold only finds his sense of self after finding friendship and ultimately in love with a spunky, eighty-year old woman named Maude, who nurtures his self-respect and joy for life. This bizarre cult classic, like Between the Temples, deals with the ability to cope with death in the face of an indifferent formal society. And both protagonists find their voice through unconventional relationships that subvert the expectations of their families. Between the Temples thus stands as a Jewish suburban variant of Harold and Maude, less macabre and ultimately more endearing.

After a century of cantorial movies, we have seen a dramatic change from the cantor struggling with the lure of the stage to the cantor struggling with the loss of meaning. Both generation of cantor is struggling with pain and alienation, particularly from family itself. The depressed Ben’s line after he leaves home — “I live in the world” — parallel’s that of the jazz singer’s own mother a century before: “He's not my boy anymore—he belongs to the whole world now." Then as now, where shall the cantor feel at home?

Between the Temples ultimately fails in helping its cantorial protagonist or viewers feel at home with Judaism or God. But what the film lacks in taking Judaism seriously, it makes up in taking human kindness seriously. And that, like a bat mitzvah, is worth celebrating.

Thanks to my colleague, Rabbi Cantor Jeremy Lipton, for this reference.

This is probably not a great look for the Empire State. As Ben quips to a priest about the lack of afterlife in his faith: “In Judaism we don’t have heaven and hell, we just have Upstate New York.”

If someone has written something detailed about the socialization of American clergy (particularly Jewish ones) into the world of golf, please send it my way. This is as much as I have found, and I can only surmise that its origins developed in Jewish country clubs where rabbis courted synagogue donors. But I am sure that the “Jews & Golf” thing goes deeper than that. My grandfather z’’l attempted to teach me when I was a boy, but it did not go well. I still relish mini-golf; beyond that my fairway experiences are limited to a summer as a country club restaurant waiter. Perhaps there’s a punchy article on golfing cantors waiting down the line.

Synagogue-going Jews will also notice some inconsistencies in the film, including Ben’s kashrut practice. The synagogue is also of ambiguous denomination, using a Reform prayer book but with the trappings of a Conservative service.

This is so well researched! And of course the granddaddy of chazzanim-turned-pop-turned back is 1940's Yiddish film Overture to Glory with Moishe Oysher. His final rendition of Kol Nidrei is worth the price of admission and turns the Jazz Singer's ending on its ear - talk about a cautionary tale.

Clearly. I haven’t seen enough of the right movies.