I’ll begin today with a hot take: The most popular composer in the history of Jewish music is trad.

This abbreviated shorthand for “traditional” adorns multitudes of music books and lead sheets, marking those melodies which we take for granted as having been around from time immemorial. Anonymity of this sort should be a compliment. After all, it is the ultimate artistic apotheosis to write something which becomes so essential that it becomes a cultural inheritance.

This principle comes to its greatest fruition in the books of the Hebrew Bible. Their divinely-inspired authors remain unknown besides Moses, the composer of Deuteronomy, and the classical prophets, who wrote their own books. Because these works were so transcendent and communally acclaimed as divine writ through a thousand years of Jewish civilization, they became —or perhaps remained since their beginnings— only traceable to God Himself. This sacred anonymity mirrors Maimonides’ second-highest level of tzedakah: both the giver and the recipient are anonymous, making space for recognition of God as the ultimate source of the mitzvah to both parties.

Thank you for reading Beyond the Music! If you enjoy reading this newsletter, please consider supporting me with a paid subscription.

This is also true in the Oral Torah. The “stamma” of the Talmud — the anonymous voice of each Talmudic tractate — is instrumental in framing the recorded debates and stories of countless sages across the generations. The Mishnah, in contrast, encourages protections for rabbinic IP, advocating that religious teaching always be quoted b’shem omro — in the name of the one who first said it.1 Although we recognize the Mishnah’s redactor as Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi (c.135-217 CE), the voice(s) of the Talmud remains unknown, inviting the learner into the conversation through their anonymity.

We don’t live in a culture today where such anonymity is often valued. In fact, we worry more about the rapacious behavior of AI and media companies which seek to own and abuse human creativity rather than foster it. The “Happy Birthday Song,” Mildred and Patty Hill in 1893, was “acquired” by the media conglomerate Warner/Chappell earlier this century, leading to a major copyright lawsuit in 2016. The company ended up settling $14 million in wrongfully claimed royalties, and the song has been returned to the public domain. Birthdays are now much happier indeed without worrying about owing big bucks every time the cake comes out.

Jewish music is almost always an oral tradition, so anonymity is more the rule than the exception. “Traditional” is just one term encompassing the common ownership of many orally-passed melodies. Sometimes people identify these melodies by the major composer in their genre. Songleading which “sounds like Debbie Friedman,” or niggunim which “sound like Carlebach (or Joey Weisenberg)” are a testament to the genre-defining accomplishments of these artists. Yet the more timeless the art, the more likely no one will ultimately know that you made it.

But today I’d like to recognize two Jewish composers b’shem omro — as individuals who created timeless classics that have lived on past public memory of their good works. The first is American Rabbi Israel Goldfarb, the doyen of Jewish communal singing at the turn of the twentieth century who, with his brother Samuel, created such synagogue hits as Zochreinu L’Chayim, Magen Avot, and Shalom Aleichem.

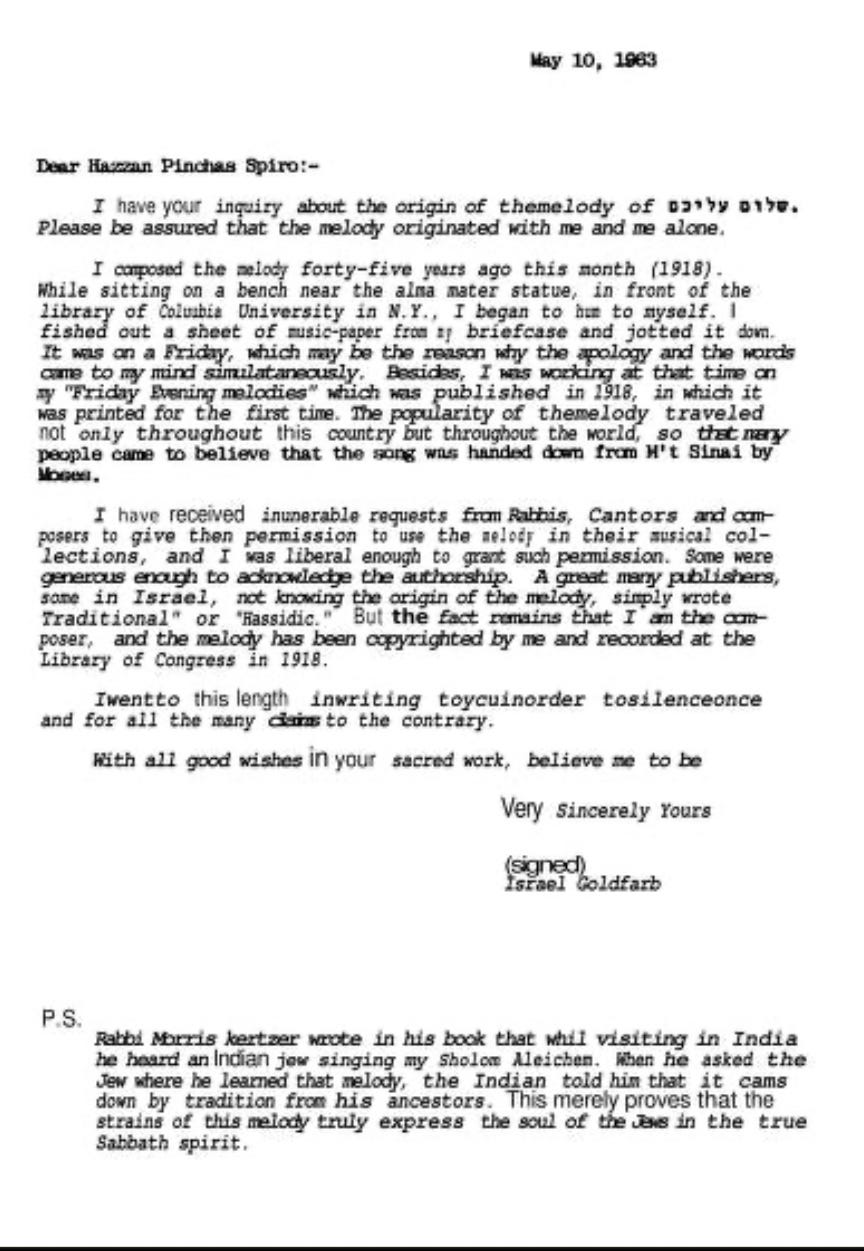

This last one, written on the steps of Columbia’s Low Library in 1918, had already passed into anonymity by mid-century, with Jews across America attributing it to “traditional.” The great nusach teacher Cantor Pinchas Spiro once wrote to Rabbi Goldfarb to confirm his authorship of the tune. In the letter transcribed below, Goldfarb claimed his authorship and copyright, but also enclosed the original music, which had changed significantly through popular transmission.2

Goldfarb’s melodies continue to form the soundscape of the entire Jewish world. He wrote above about their travels as far as India. Just this past week, their far-reaching power was re-ignited as former hostage Daniella Gilboa reported having sung his Sholom Aleichem in Arabic while in Hamas captivity, since her captors forbade the use of Hebrew. The melody of this timeless song kept her spirit going, even in the most inhuman of conditions.

Anonymity may be religious culture’s greatest compliment, but the Mishnah rightly encourages us to honor the real creators behind our current sound. One day I hope to do a fuller series on “Where the Tunes Come From,” an examination of the wide-ranging composers and historical sources which comprise the “trad” American synagogue repertoire.

In the meantime, I will close by giving a shoutout to a cantor whose innovation will be heard around the world on Thursday night’s celebration of Purim. R. Yuda Hazzan (d.1700), cantor of the Pinchas Synagogue in Prague, was recorded on his gravestone as having been the first person to sing the High Holidays “HaMelech” as a musical diversion at the beginning of Chapter Six of Megillat Esther. The Ashkenazic tradition of adding special melodies to Esther is an old one, but rarely do we know one of its creators by name. The innovator’s identity was confirmed by Rabbi Yosef Kossman, who personally heard R. Yuda’s in Prague and recorded it in his book of customs, Noheg Katzon Yosef (1718).3 Though R. Yuda Hazzan enjoys no celebrity today, his creativity will still be heard in this week’s Purim celebrations all over the world.

This Purim, we should take the time to appreciate these little-known creators. The Book of Esther does not mention God’s name at all, and yet this powerful anonymity is actually what invites us to seek God behind the story. From “Shalom Aleichem” to “Happy Birthday,” may moments of knowing (or not knowing) the creators of our traditions remind us that they are ultimately anonymous gifts from the true Creator and author of our lives.

Mishnah Avot 6:6: “…. Thus we have learned: One who says something in the name of its speaker brings redemption to the world, as is stated (Esther 2:22), "And Esther told the king in the name of Mordechai."

The structure of the song used to be A-B-B-A; popular use flattened the melody and shifted it to A-B-A-B. For the full story, see Pinchas Spiro, “Israel Goldfarb’s Shalom Aleichem,” Journal of Synagogue Music 16/2 (1986): 38-46.

See Abraham Tzvi Idelsohn, “Cantors from Famous Communities: Prague,” Reshumot 5 (1927): 351-361 [Heb.].

The bane of my existence is having to write “folk”, “Israeli”, or “trad.” at the top of music I arrange for choir. I do my best to find the composers and lyricists, but it’s often not possible. Still, sometimes I start with a photocopy of a photocopy, the top of which says trad or folk, and after some Internet searching, I find an actual composer. Then I’m glad to add my name as “arranger” to an attributed piece.

Thanks, kol hakavod for the teaching