Next weekend is Rosh HaShana, the Jewish new year, in which Jews will gather to proclaim God as King and of the whole world. The religious music of this season is equally royal, and even the most hierarchy-free prayer groups will intone long-reigning majestic melodies which cannot help but enthrone the LORD in sonic sovereignty.

It is also a day of leadership. Cantors, rabbis, and ba’alei tefillah prepare for months with volunteers and staff to create a well-run and prayerful experiences for their whole community. It is also a time in which they must unite their diverse people around shared purpose. And so as the audience with the Heavenly King and His subjects nears, leaders are are reflecting on how they shall lead.

As a lifelong Anglophile, I watched many seasons of Netflix’s The Crown with great delight. Yet as the show continued, I began to feel strange parallels between the Queen’s experience of leadership and, in small bizarre ways, my own experience of leadership in the cantorate. So in the spirit of these upcoming days of extended monarchical metaphors, and in honor of the one-year anniversary of the passing of Queen Elizabeth II (last Friday, September 8th), allow me to explore this perhaps odd juxtaposition of queen & cantor.1

One of the core qualifications for Jewish prayer leadership is being fundamentally agreeable to those one represents. 2 At the end of this week, prayer leaders throughout the world will say the hineni, professing their aspiration to be m’urav b’da’at im hab’riot - pleasant in the hearts and minds of the people. Cantorial laws even require that one actively work to settle differences with community members so that one will dutifully and wholeheartedly represent them before God.3 Popular mysticism further envisioned the cantor as in the place of the high priest, therefore exhorting him to be filled with compassion in order to activate God’s own compassionate qualities:

One must know the reason for why the only appropriate work on Yom Kippur is that of the High Priest. You already know that the secret [sod] of the High Priest is compassion [chesed]. And on this holy day, which is a day of atonement, forgiveness, and mercy, it must be that the quality of compassion overcomes the measure of judgment, since if there is no compassion, there is no atonement or forgiveness!

And if you call upon a common priest, who is inclined to the measure of justice, perhaps the compassion will be tainted with judgment. Because of this, on this day in which dominion is given over to the World of Compassion, from which atonement and forgiveness comes, the prayer leader must be mercy—that is compassion that does not stand on judgment, and review his qualities in order that he shall bring forgiveness..

…And behold now we have no High Priest, only the prayer leader. The cantor must be in the place of the High Priest: pure and steadfast, reviewing his qualities as we said before. And if he has a voice which is pleasant to the spirit of humanity, then of course it will be pleasant to the spirit of God.4

This aspect of the cantor’s role, to be a trusted, compassionate, and even beloved representative of people to God, is the partial root of the great ethical strictures surrounding the prayer leader’s qualifications. The lists of these qualifications, which appear across the generations of Jewish law, represent each generation’s highest ideals for personal piety and humility.5 Like the biblical priest, the prayer leader is closer to God, yet lives a life of limits which allow him or her to be unifying symbol for the community’s moral aspirations.

These qualities — of being a beloved representative of the community, taking on personal restrictions for leadership, and unifying people —are also all aspects of the ideal functions of British monarchy (at least as portrayed in the Crown). Amidst the normal and necessarily change in democratically-elected government, the constitutional monarch, as

put it, “acts as a focus for unity…enshrining the identity of the nation above and beyond temporal politics.6”If you think about it, this description is not much different from the ideals of a typical congregational for its rabbi or cantor. Besotted with politics and personalities, how many synagogues (or membership-based organizations in general) are not yearning for leadership that brings them together with compassion, inclusion, and unity?

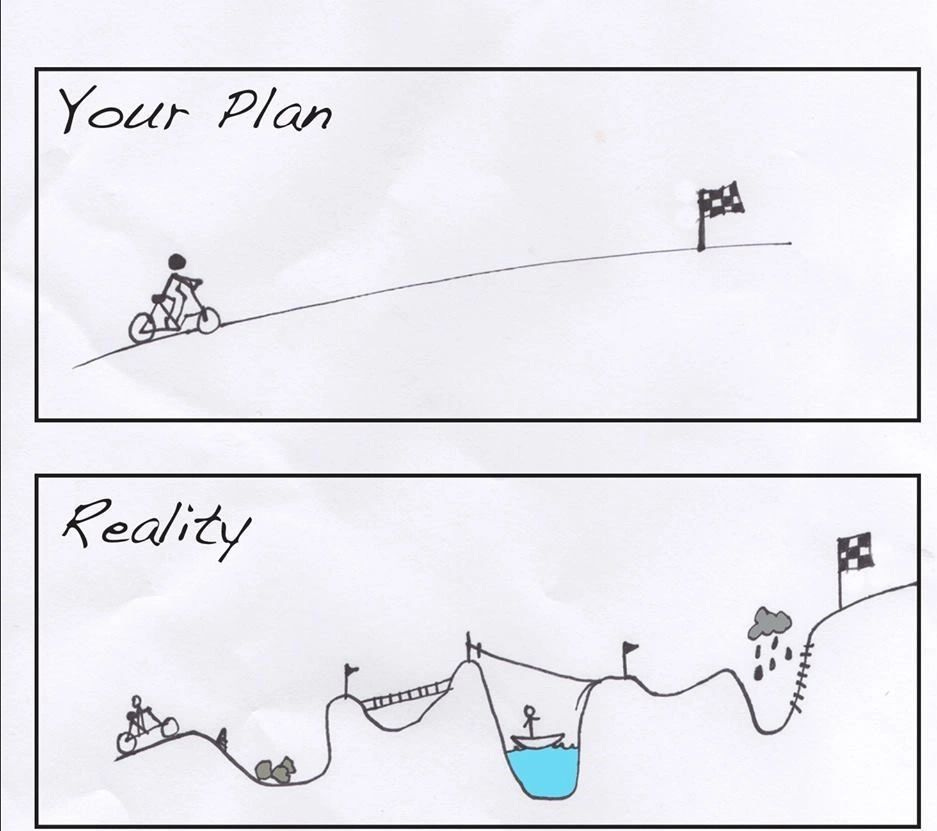

But such ideals and reality are often quite different. You can watch the Crown, but you don’t have to live too long to know that so many of our idealized figures fall well short of our great aspirations. Some of these idealized figures are ourselves. Does the fault lie in us, or in our stars?

Being m’urav b’da’at im habriot is hard and exhausting work; no one can (or should) please everybody. Yet we still long for ways that we can create inclusive, compassionate relational life, bringing our communities (or our countries) together. In a way, music itself does part of this royal work, powerfully bonding people in song. It is no surprise that King David (our hero last week) was as good at weaving twelve tribes into the fabric of nationhood as composing twelve tones into a song.

This week, prayer leaders will try to embody this regal ideal of unity, and the priestly vocation of becoming compassion. Rabbi Shai Held sensitively echoes and expands this work to include all of us. At this time of year, he writes that we must “be the love and the goodness we pray for",” and that “the process of opening our hearts to God and opening them to each other are necessarily entwined.” Not just the rabbi, or the cantor, or the prayer leader, but the whole people.

We long for (and often appreciate) leaders who review their qualities and embody compassion, and we pray that Avinu Malkeinu - Our Father, Our King - will be the ultimate source of such compassion. But we we too must be the compassion that we want to see in the world and that we hope to receive. For each of us are like kings in the eyes of God7, with the ability to bring that same compassion, inclusion, and unity to ourselves and to others.

Next week, I will write more about The Crown and a surprising scene which illuminates the unconscious (and controversial) social functions of the cantorate, just in time for us to acknowledge our sins before Yom Kippur. In the meantime, for those who celebrate, I wish you a k’tivah v’chatimah tovah - may you be inscribed and sealed for a good year.

NEWS: I am currently in the planning stages of organizing a Jewish Sacred Music Tour of the UK in mid-late June 2024. The tour will feature a choral Shabbat, encounters with Jewish communities, cantors, and rabbis; great lectures from musicologists; visits to Oxford and Cambridge for viewings of unique manuscripts in Jewish music history, a visit to a Jewish country house, and plenty of singing and musical events. If you are potentially interested, please reach out and I will put you on the email list for updates.

Full disclosure: I’m not here to engage in the question of the merits of either institution, attacked as they both have been in recent years. As I hope to demonstrate, the dynamics of royal leadership nevertheless remain surprisingly instructive for understanding the overt and covert socioreligious functions of the cantors (and rabbis), and of music in society more broadly.

The inherently democratic nature of the role of sheliach tzibbur is a fascinating subject of study. Born of an impermanent, relationally-determined role in rabbinic Judaism, the history of the the permanent or institutional sheliach tzibbur (known as the hazzan / cantor) is a rollercoaster of social history as rabbinic leaders and lay boards tossled over cantorial candidates and who had the authority to appoint or remove a cantor. Orthodox and orthopraxis Ashkenazi communities, which have largely dispensed with the institutional cantorate, have often nevertheless retained the title of hazzan as a function, even if it is devoid of the financial terms and professional status that Jewish communities gave to this important office for nearly a millennium. In other words, “cantor” has become a verb, rather than a noun.

An interesting counterpoint to this is the little known cantorial privilege to exclude people from their prayers, thus leaaving their obligations to God in prayer unfulfilled. For a great study of this phenomenon, see David Berger, “The Cantorial Power of Exclusion,” Journal of Synagogue Music, Vol. 45, No. 1 (Akron: Cantors Assembly, 2020): 111-126.

Rabbi Shlomo Lifschitz, Sefer Teudat Shlomo (Offenbach: Seligman Reis, 1718).

For example, see Shulchan Aruch, Orach Hayyim 53. https://www.sefaria.org/Shulchan_Arukh%2C_Orach_Chayim.53.4?lang=bi&with=all

Melanie Phillips, “The Momentous task for King Charles III,” September 16, 2022.

One way this is represented is by the wearing of tsitsit (fringes), which were symbol of divine relationship previously only given to Ancient Near Eastern kings or priests. Spiritual leadership and divine relationship were democratized in the Hebrew Bible, leading to the conception of the Israelites as a mamlechet kohanim v’goi kadosh - a kingdom of priests and a holy nation.

Thanks for this. In my father’s last weeks, encompassing all of the fall chaggim (his yahrzeit is 8 Cheshvan), he derived great comfort from re-watching The Crown —one of his favorite shows— with us. Even on the night before he died, when he was barely able to speak anymore, we watched and talked about the show. The approach to the holidays without him these last two years has been bittersweet, but somehow, your linking this time of year to The Crown hit the exact note I didn’t know I needed. Thank you for that!