Idelsohn & Israeli Democracy

What the father of Jewish Musicology can tell us about Israel’s political moment

Welcome to Beyond the Music, a new commentary on Jewish musicology, arts, and culture! I’ll be posting every 1-2 weeks; you can subscribe below to receive this regularly in your mailbox.

This past week the Jewish world had lots of tough feels. The mournful fast day of Tisha B’Av, commemorating the destruction of the Jerusalem Temples, followed shortly after the Israeli Knesset’s passing of controversial legislation modifying the oversight capacities of the Israeli Supreme Court. Trust between different parts of Israeli society is at an all time low, with rising concern for the democratic institutions of the State. Many of my colleagues could not help but invoke the communal sin of sinat hinam, or wanton hatred, that is becoming difficult to overcome. As the Book of Lamentations says, al eileh ani bochiya, “for these things I weep.”

This level of discord is a din beyond the divine disorder of the synagogue. Can clashing voices such as these pray together, or make the music of a nation together?There are reasons both to doubt and to hope. But let’s take a surprising lesson on Israel & democracy from an unexpected source — the “father “of Jewish musicology, Abraham Zvi Idelsohn.

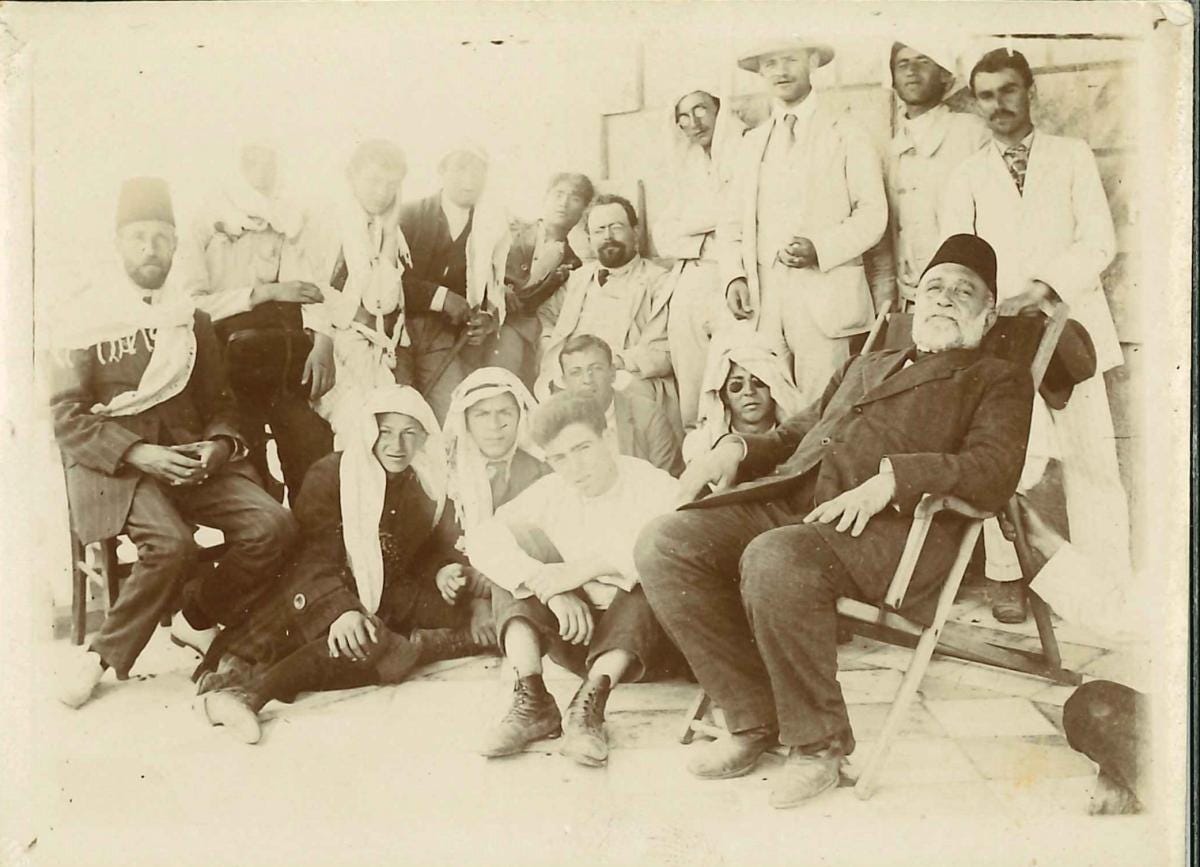

A.Z. Idelsohn (1882-1938) had neither a typical academic training nor a typical academic agenda. He was born in Latvia, where he was educated in yeshiva and as a cantor’s apprentice. His only formal training was in music, spending a brief stint studying in Berlin and two years at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Leipzig. In 1907, after several short-lived cantorial pulpits, a Idelsohn moved to Ottoman Palestine, where his (largely self-taught) scholarly work would take root. He engaged in a wide variety of musical activities and conducted ethnomusicological studies of the local Jewish communities, all before leaving for the United States in 1922, where he established his reputation as an authority on Jewish music. During this very moment of ascent, and just prior to becoming Professor of Jewish Liturgy and Music at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, Idelsohn published an extensive study of the cantor - HaHazzan B’Yisrael (“The Cantor and the Jewish People”). This Hebrew-language essay reveals much of Idelsohn’s worldview, as well as his ideas about democracy and the Jewish people.

Full disclosure: I have been warned about quoting Idelsohn. Even though his books and articles are the starting point for all Jewish musicologists, his idiosyncratic theories, numerous errors, and essentialist notions of “authentic” Jewish music have rightly made him the subject of criticism.1

But I’ll tell you a secret: I kinda love him for it.

The contemporary criticism of his scholarship is totally on point, but what remains endearing is his deep and unvarnished motivation to create meaning, not just truth.

The tension between Idelsohn the Cantor vs. Idelsohn the Scholar is on display in HaHazzan B’Yisrael. He begins his essay with a statement of the uniqueness of the ancient Israelites:

The worship of idols or the worship of many gods by animal sacrifices dates from time immemorial; praise and thanksgiving during these sacrifices was also offered by the Assyrians and Babylonians, as witnessed by their cuneiform records. But pure prayer, prayer alone, without sacrifice, the service or the heart, was created by the spirit of Israel.

The nobles of Israel aspired to express their feelings to their God, who was like Father to them, and they did not satisfy themselves with sacrifice alone, but rather pouring out their thoughts and meditations at each suitable time. And every Israelite, man or woman, was allowed to speak directly to the God of Israel without an intermediary, with neither a hereditary priest nor a priest by decree of the god-king, as was customary in Egypt, Babylonia, Greece, India, and China..2

If this reads less like history and more like a nationalist narrative, that’s because it is. Idelsohn was writing in the Hebrew-language journal HaToren, a longstanding periodical published by the Hebraist intellectuals and elites of New York. This chronicle of cantors would not be evaluated by the academy, but by fellow Hebrew champions like Idelsohn trying to convey the richness and value of Hebrew language, Jewish civilization, and Zionism to their readers.3 HaHazzan B’Yisrael also became the main source for Idelsohn’s cantor-related material in his “academic” magnum opus, Jewish Music: its Historical Development (1929). Articles like this give us more realistic expectations of Idelsohn’s writing, which were ultimately both practical and ideological aims rather than academic ones.

Second, Idelsohn is leading his history of the cantor by lauding the spirit of the Jewish people which democratized direct access to God, beyond the sacrificial cult. Some of you might smell what’s coming — what about the cantor? Don’t cantors, as uplift the service as a sort of “musical priest” whose beautiful adornment and expert execution of the prayers facilitates meaningful worship?

Idelsohn’s objection, as we will see, is neither to skillful nor musical prayer leadership. He is wary of systems which appear to obscure this original, equitable access to prayer. Judaism had no ritual priesthood, as in Catholicism, by which essential rituals could only be administered or sung by an ordained clergy person. But the institution of a “permanent” cantor may give the impression that prayer leadership (or even prayer itself) is his exclusive domain.

Later in the article, Idelsohn continues by addressing this issue and reminding the reader of the inexorable relationship between prayer leader and community — for good and for ill:

For even if the cantor took ownership of the ark, and pushed away the feet of the common worshiper, nevertheless it remained in the nature of the Jewish people that a simple Jewish gentleman could go before the ark if he was a decent person, knowing the meaning and the nusach of the prayers, that is to say he melody of traditional prayer. And if it was a fast day, they would honor an important person, and from this there remains the custom to honor the rabbi or an important community member with [leading] Neilah of Yom kippur. And the standards of the prayer [leader] or sheliach tzibbur was a gauge of the Hebrew & Judaic knowledge of the congregation. If there were people who were accustomed to the prayers and who could go before the ark, it was a favorable sign for its Jewish character; and if not, it was known that ignoramuses have prevailed in the community. 4

Idelsohn, an amateur yet accomplished historian, knows well that cantors are not the beginning and end of prayer. It is the congregation’s ability to be full citizens in prayer that is a “siman tov” — a good sign. Idelsohn deepens this critique with a particularly stunning observation from his unique knowledge as a traveling cantor and ethnomusicologist:

Thus you have almost no Yemenite, Moroccan or Iraqi, Lithuanian or Pole who is not versed in the prayers and traditional melodies and is qualified to go before the ark, at the same time that almost no Jew in Germany, France, Italy, and even amongst European Sephardim that are able to go before the ark. For this reason, in Yemen, Iraq, Morocco, and Lithuania the role of prayer [leader] and sheliach tzibbur remains in its ancient form, as it was handed down from Moses, Our Teacher, a matter that every person of Israel should be fitting to do, the property of all and a folk-based, democratic inheritance; at the same time that Germany, Spain, Italy, etc. have almost lost the memory of the lay prayer leader, and thus make the cantor the only prayer leader, on behalf all of his community, and without him one would find neither hand nor foot in the synagogue.

Cantor Idelsohn cuts me to the quick. He observes that only communities who kept a lay tradition of prayer leadership have maintained actual widespread knowledge of prayer. And he knows this for a fact because he has studied these communities and documented their music (Idelsohn published his ten-volume Thesaurus of Hebrew Oriental Melodies beginning in 1914, with much of its content derived from work with his musical informants in Jerusalem).5

Yet it is among Western European Jews, whose enlightened musical creations and choral works were the standard bearers of Jewish musical beauty, that prayer has become like a priesthood— the property of a musical few, leading to the abandonment of competence in prayer among the people altogether.

This view is hauntingly contemporary. Jewish educators and practitioners of “Empowered Judaism” are now responding to current iterations of this same phenomenon. Their approach to Judaism and community is one in which the commandments, including prayer, are, as Deuteronomy enjoins:“not in the heavens…but very near to you, in your mouth, and in your heart, to do them.6” In our era of disintermediation and troubled institutions, where does this leave the cantor?

Has Idelsohn come, like Marc Antony in Shakespeare’s Julius Caeser, to praise the cantorate, not to bury it?

This question is deeper than it appears, and it’s not just about cantors. It is really a question of how Jews authentically (and religiously) approach things like beauty, hierarchy, complexity and specialization — both in Judaism and in music.

But for today, we’ll have to put the vast lines of inquiry inherent in that question in the “parking lot,” as we continue into Idelsohn’s next statement about the cantor, in which he reaches his great praise of democracy and the character of the Jewish people:

This position of honor, a position only for the sake of heaven, a position specifically of holiness, like that of the prayer [leader] or the sheliach tzibbur who volunteers to entreat on behalf of his people, there is no parallel in any other nation or faith before Judaism, and only the early Christians saw and imitated it in the Christian sects of England and America; Nevertheless, the folk and democratic spirit that abides in this position [maintains] that each person from Israel should be able to approach and to entreat mercy before the King of the Kings of Kings. It is one, whether a the person has the crown of Torah, riches, and honor, or he skins carcasses in the shuk (Heb. market) in order to avoid destitution, provided that he should be wealthy in virtue, of good heart, soul, and voice. Such a spirit could only be achieved by a people that created the most wonderfully humane and democratic laws in the world!

God shed his grace on thee — Idelsohn, himself a new immigrant, here connects the democratic nature of prayer leadership in Judaism with the religious heritage of the USA. He puts Jews on shared ground with the English and American Protestants who not only democratized their ministry, but who were among the founders of modern democracy.

Idelsohn’s political environment also puts this statement in important context. When this article came out in 1923, European fascism was on the rise. Adolf Hitler’s failed coup in Munich would occur later that very year. So too at home, xenophobia was rampant and Jews were at pains to prove their Americanism and the value of their civilization to the American project. Idelsohn’s focus on democracy thus evokes both a contrast with European fascism and expresses Idelsohn’s own bid towards a Jewish Americanism which is typical of this era.7

On another level, Idelsohn is connecting the democratic nature of prayer leadership to a broader vision of democratic and humane laws, which to him are essential to the spirit of the Jewish people. His idea of the interpenetration of democratic notions throughout Judaism may be ideological, but I believe it is a true assessment of how Jews have enacted the principle of tselem elohim8 — that all human beings are made in the image of God, of both equal and infinite value.

To conclude: For me, looking out at the protests in Israel, I see a nation of people who believe and enact just that. Like prayer for Idelsohn, Israeli politics is not the sole domain of the priests (or politicians) — it is an obligation for the whole people, as hundreds of thousands gather to stand up for a vision of their country. Even in this political maelstrom, Israelis have found moments of mutual respect and heartfelt patriotism. I am not pollyannish about the depth of distrust that has been sewn, nor the looming crisis of governance. But I am optimistic that this is nation will find its resilience in its societal values of commitment and service. Heartbroken as he might be, as we are, to see what we are seeing today, I think Idelsohn would still be proud of that democratic spirit. Let us hope and pray that it leads to good.

Next time, we’ll get back to more music with “Is There Jewish Harmony? (Part 3), in which I’ll share some fascinating pre-modern Jewish musical experiments with Western harmony. If you can’t wait that long and have your whistle whet for Idelsohn, take a listen to this Shir HaMa’alot, one of his many choral compositions. Much thanks to my friend, conductor and composer Ohad Stolarz (himself an Idelsohn scholar) for the recommendation. Also my thanks to colleague Judy Pinnolis for reviewing a draft of this post.

Blessings to all for a week of nechama (consolation) as we begin the walk towards the High Holy Days.

Idelsohn often overstated the historical “authenticity” of Jewish music on ideological and nationalist grounds. As he wrote in his Hebrew autobiography: “My opinion was that if there is authenticity in the Music of Israel, then there should be common foundations for all of the communities. And if common foundations like these exist for all of the communities, these are the sparks of the National Soul –– the original Hebrew Music.” This text is part of a new, online compilation of Idelsohn’s autobiographies and memoirs by Edwin Seroussi & Yonatan Turgeman of the Jewish Music Research Center.

For another astute critique of Idelsohn, see Judit Frigyesi’s most recent article on Eastern European Jewish prayer chant.

Abraham Zvi Idelsohn,“HaHazzan BeYisrael,” HaToren [my translation], Vol. 10 no. 3 (Sivan 5683): 62. My thanks to Ohad Stolarz for helping to refine my translations.

By the time Idelsohn published, HaToren was already in its waning years. For an insightful study of the history of HaToren, see Alan Mintz’s article, “A Sanctuary in the Wilderness: The Beginnings of the Hebrew Movement in America in the Pages of Hatoren (1990).”

Idelsohn, ibid, 71-72.

Idelsohn’s ethnographically-informed critique is not a new phenomenon. In 1700, a concerned citizen (likely a rabbi) in Amsterdam published an anonymous poster called Shlosha Tzoakin V’Einan Na’anin (“Three cry out, yet none are answered”) excoriating Ashkenazic cantors, and saying that the liturgical singing of each group of Jews in the rest of the diaspora was far superior. For analysis, see my masters thesis, “A Pleasing Aroma: Prayer Leadership and Cantorial Ethics in the 18th century,” page 7-8.

Deut. 30: 12, 14

For more on American Jewish anxieties in the years following World War I, see Jonathan Sarna, American Judaism: a history (New Haven: Yale University, 2004): 208-271.

Cf. Gen. 1:27.

GREAT article, connecting Music, History & Politics. Kol haKavod!

Only one minor historical error, I think: You said he settled in British Palestine in 1907, but in that year, it was still Turkish/Ottoman Palestine.