Among the more colorful events of my travels, I recently performed an inventory of a rare book collection which had been locked in a long-neglected synagogue library cabinet. The contents were mind-blowing — a treasure trove of over one-hundred and fifty pre-modern volumes dating back to the fifteenth century. Here’s just one example:

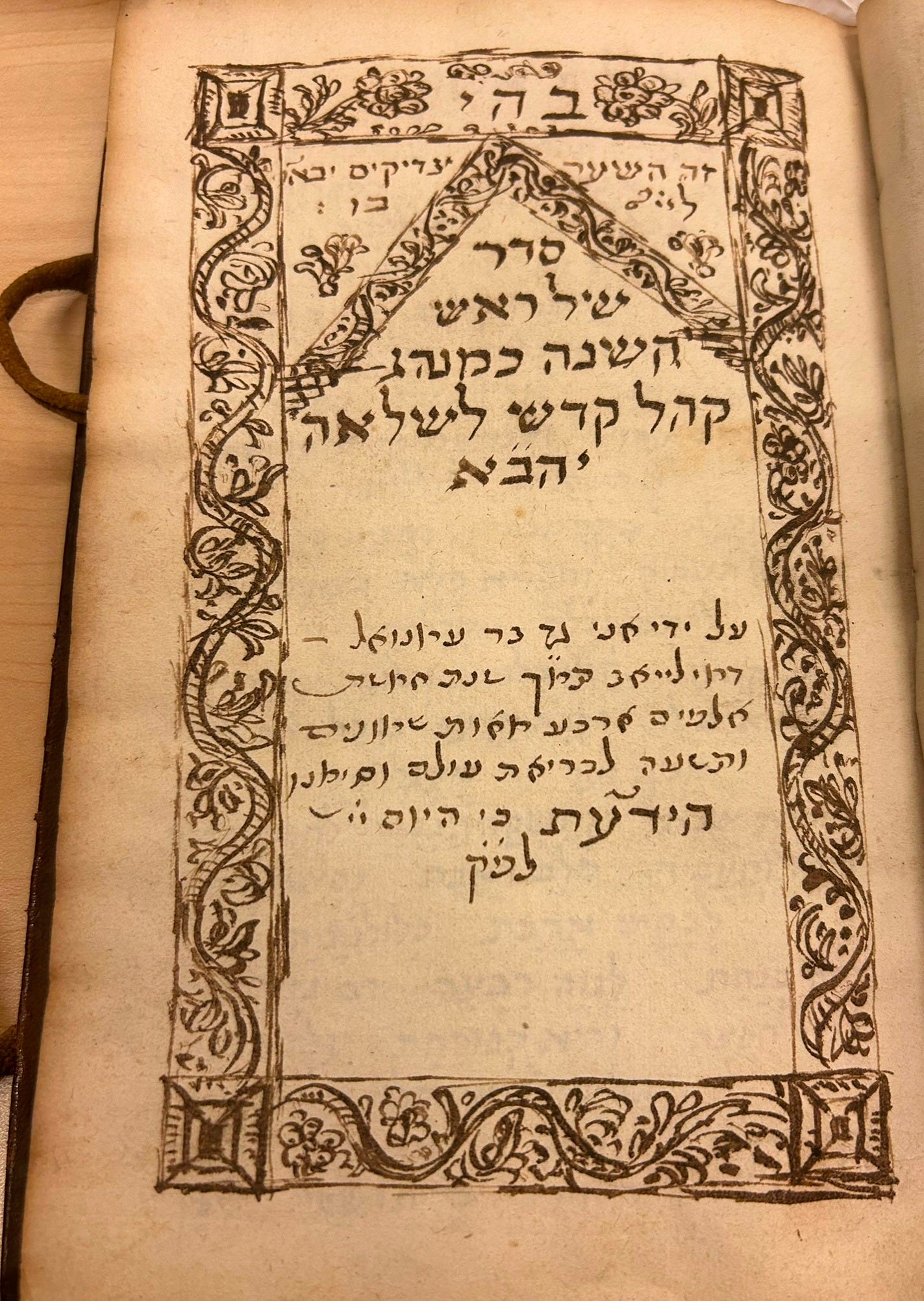

This handwritten prayerbook (c.1730) for Rosh HaShanah hails from the French-Jewish community of L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue in the region of Provence also known as Comtat Venaissin. Its four Jewish “holy communities” of L’Isle, Avignon, Carpentras, and Cavaillon date back to the Avignon papacy in the fourteenth century. The manuscript’s author, Gad bar Emanuel de Milhaud, was from a long line of scribes, and the very same family as the famous French composer, Darius Milhaud.1 Milhaud was passionate about his childhood synagogue soundscape (you can read in his own words), which his family was part of inscribing in parchment for generations, including this very book.

And that was just one volume! As I leafed through more and more, uncovering owner’s inscriptions, rare manuscripts, and fascinatingly unique books, I uttered the impassioned words of a former faculty member at Marshall College in Bedford, Connecticut:

It is truly amazing what you can find in synagogue libraries and museum cases. I haven’t quite located the Ark of the Covenant, but I have witnessed displays with unpublished letters from Sir Moses Montefiore, eighteenth-century Italian music books, three-century-old Yemenite Torah scrolls, and countless silver pieces of antique Judaica.

Thanks for reading Beyond the Music! If you enjoy this newsletter, the best way to support me is with with a paid subscription.

Most synagogues have a display case or two (or more!) of this kind. Yet I can’t help feeling that these items could have more exciting lives. Languishing behind glass, it is rare that synagogue treasures are exhibited in eye-catching, curated ways that draw people in to learn (my local Maltz Museum is an exception). Furthermore, some of these private collections are potentially very significant yet obscure sources of Jewish history. Hiding in the synagogue, the academic world may never learn of their existence.

Here’s a prime example:

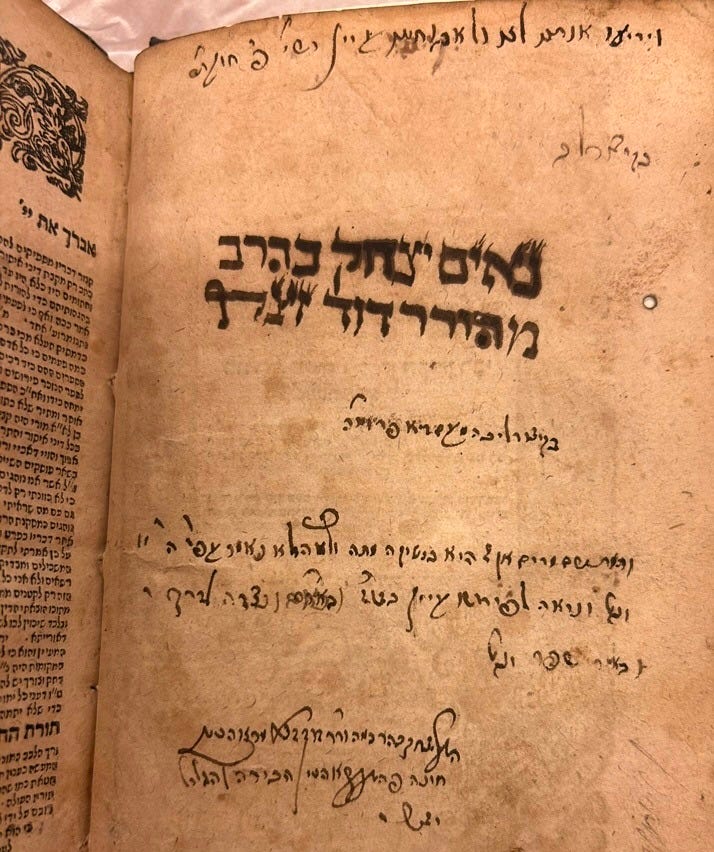

This well-kept, 1628 edition of R. Moshe Isserles’ Torat HaChatat is covered in marginalia and pen testings from its former owners. Sacred scribbles like these are at the heart of unlocking the forgotten stories behind the books, illuminating the personal thoughts and lost collections of our ancestors. The Footprints project, based at Columbia University, takes these inscriptions and uses them to construct digital maps of Jewish book journeys and of the lives of their authors. As the great library champion, Levar Burton, once said: you don’t have to take my word for it.

Our synagogues, and our world at large, are still full of these hidden Judaic treasures waiting to be discovered and explored.

Exciting, no?

Alas, I wish I believed that there were an army of academics, rabbis, cantors, and Jewish minds ready to reclaim the legacies of the historic Jewish “displayica” across our great land. All of these folks probably have other important things to do.

But let me make my case with one final point, which comes from a lesson that I will never forget.

The English concertina player Randy Stein once gave a d’var torah (sermon) at my synagogue on the experience of going to a Jewish museum and having a profound realization: that museums, more often than not, hosted the objects of conquered peoples. Their holdings were obsolete, reflecting societies whose ways of life were so transformed by modernity, time, or cultural imperialism that they no longer required them. His message to us was: don’t let your Jewish objects become a museum pieces. Use them.

Think about it. There is no Hasidic museum. There is no Hadar museum. There is no Camp Ramah museum. This is because active movements do not require museumification to mitigate the loss of a fleeting past.

Don’t get me wrong — I love museums. Our family goes to them all of the time. But a good museum tries to engage you in a way which deepens your understanding and attachment to history, its stakes, and its lessons. Not as a form of schatzkammer to display precious donations. Or, more lamentably, as a place to store notable religious or cultural items which have otherwise fallen into disuse.

Old things may be worth something. But their story is worth even more.

And even more than this is the worth that something is given by active use. Your grandfather’s tallis, your great-grandmother’s candlesticks, your family’s heirlooms — these things are better well-loved and well-used than simply well-preserved.

I got a shocking reminder of this when I first visited the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. Looking down at an exhibit on Passover across the Jewish diaspora, I did a double-take. In a little display case was a piece of my own Passover seder — an afikoman bag souvenir from the Rav Hayyim Berlin Yeshiva in the early twentieth century.

For the Israel Museum, this was a piece of memorabilia from the American Jewish community. For me, it was identical to our own afikoman bag — a gift that my grandfather received in Brooklyn as a young boy, and which connected me to over four generations of Passover celebrations in my family.

One person’s museum piece is another’s path to mitzvah.

Let’s not permit ur precious heirlooms become the relics of a way of life conquered by modernity, apathy, and time. Instead, let’s use them to know our history better and to actively celebrate our Jewish lives.

Then we will have chosen…wisely.

The twentieth-century Milhaud, a member of the elite group of neoclassical French composers known as “Les Six” and writer of nearly 450 works, was a Jew who grew up the Provençal synagogues of this special and remote region of France. He created a number of classical works which incorporated liturgical melodies of his youth. Here’s one:

Dear Matt, I appreciate your interest in our collection and your valuable input in identifying the books. I do want to stress that Congregation Mishkan Or of Beachwood, Ohio, takes very seriously the responsibility of stewarding our fine collection of Jewish ritual objects, fine art and rare books. Rabbi Abba Hillel Silver, who founded in 1950 what was then called the Temple Museum of Jewish Religious Art and recently, with the merger of congregations Temple Tifereth Israel and Anshe Chesed, became the Mishkan Or Museum of Jewish Cultures, had an acute understanding that material culture forms an inseparable part of Jewish spiritual life and education. Our museum plays an active role in preserving this material legacy and educating our community and the wider public. Many of our artifacts are not just displayed but are used in services and educational programs and are given as loans to other institutions (recently for the Cleveland Museum of Art). Our community member are actively involved in planning the programs and taking care of the objects.

Allow me another clarification – the Judaica Gallery at the Maltz Museum, which you have favorably mentioned, presents the highlights from the 2000 objects strong collection of congregation Mishkan Or. Maltz Museum itself is not a collecting institution. With the merger our museum and library received a great addition of objects and books, some of which you had the pleasure of exploring. We are in the process of gradually and thoughtfully considering what to do with the treasures we received. Here at Mishkan Or we are hard at work to make our collection relevant and accessible for the congregation and the wider public. It takes constant effort and a lot of money.

Given the dwindling of federal support for culture, independent museums, including synagogal community museums and libraries however small and however few remaining, will play an ever-important role in preserving and providing access to Jewish heritage. Please support them in every way you can.

Respectfully, Katya Oicherman, Director of Mishkan Or Museum of Jewish Cultures.

How interesting that you should publish this just as I'm writing a lecture on the subject of ritual objects in museums (I'm an archaeologist and museum specialist). Paine (2017 - see link and check out the publication it references) describes museums as secular temples to conquered societies, and placing religious objects in museums removes them from ritual life, effectively making them dead objects. I'm on a mini-research project at the moment trying to see how people interact with them! I'm particularly interested in whether any of the collected objects are taken out to be used in services ever again, or if they might be too damaged (I went to a shul recently that had one of these displays with a partly-burnt Torah). I'm also thinking of de-accession policies and seeing how many museums work with a genizah - so far have found one secular collection with Jewish museum that does!

Anyone with further thoughts is welcome to email me, stacyhackner (at) gmail (dot) com

https://www.glencairnmuseum.org/newsletter/2017/3/27/religious-objects-in-museums-an-interview-with-crispin-paine