The German-Jewish composer Herman Berlinksi once gave a lecture to my high school orchestra camp. Recounting his travels to Berlin after the war, he told us of an old German woman who said to him: “I can forgive Hitler for everything he did, but not that he took away Mendelssohn.”

Berlinski’s retort to her was, let’s just say, not fit for the classroom.

The Shoah, in which the German Nazi regime orchestrated the mass murder of six-million Jewish men, women, and children, was history’s most unholy and inhuman atrocity. Yet this was not just a purge of the Jewish people, but also of any hint of Jewish contributions to European culture. Like today’s campus youth crying for decolonization, intimidation, and violence (as well as humanitarian meal plan delivery), the fire of orthodoxy and the intolerance of dissent are the hallmarks of such a mass movement. As Eric Hoffer prophetically wrote: “a mass movement absorbs and assimilates the individual into its corporate body, and does so by stripping the individual of his own opinions, tastes and values.”1

If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription (for just $8 per month).

So too, the Nazis could not envision a Germany whereby even the smallest remnant of Jewish cultural contribution sullied its culture — including in the realm of music. Following the removal of Jews from the German professions and arts (including banning the music of Jewish composers like Felix Mendelssohn), two Nazi musicologists published Lexikon der Juden in der Musik — “The Lexicon of Jews in Music.” This volume was a comprehensive inventory of every prominent Jew of musical ancestry in the world: singers, instrumentalists, conductors, composers, educators, directors, and writers.

The information in this book included birthdates, professions, and last known places of residence. But the volume was not commissioned to track people down. It was to record the Jewishness of artists so that their cultural impurity would be remembered for all time:

“This situation gave rise to the need to create a reference work that, despite the difficulty of the subject matter, reflects the state of our knowledge in an impeccable form. The most reliable sources had to be found in order to give the musician, the music educator, the politician and also the music lover the absolute security that must be demanded with regard to the Jewish question.”

This Nazi quest for purity was not an easy one, as the contributions of Jews ran incredibly deep in German culture. Hence the racist conundrum of Berlinski’s old German music enthusiast.

Yet the reason for this musical purge went deeper, to the very foundations of German nationalism, as made clear in the Lexikon:

“We measure with the standards of our race, and then we come to the conclusion that the Jew is uncreative and that in the field of music he can only advance to a certain level of technical skill through imitation. His ability to empathize enables him to achieve astonishing achievements as a virtuoso, but upon closer inspection they appear to be empty of content, especially since his oriental sensibilities always have to falsify the content of a Western musical creation.”

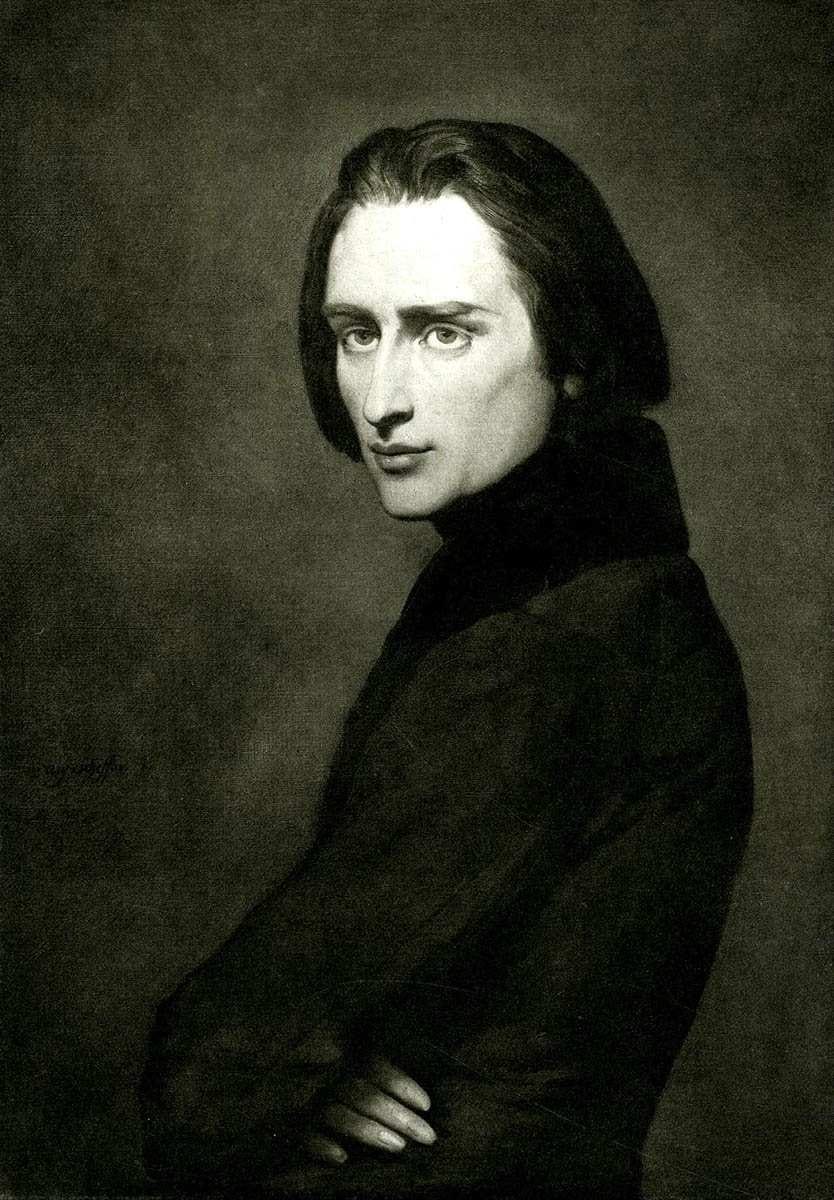

This trots out one of the classic music libels against the Jews — that a people without blood and soil (Ger. blut und boden) cannot express the true soul of a nation. Franz Liszt pointed this out nearly a century before. And the scary thing is that he could see the writing on the wall even then.

What follows is most prophetic quote in the history of Jewish music:

“What the Christians must do is consider giving them their own homeland. They are not going to accept any homeland but their own, so their Palestine, their Jerusalem, and their temple will have to be returned to them. Sooner or later we are going to have to unsheath our swords and drive them away to take it. The feeble ones are going to go down on their knees before our altars and offer their very lives to stay with us. The faithful will run to their "Promised Land," settle there, and believe it was a miracle. Oh, God! That will be a miracle indeed--a true miracle--to see a people that, after 20 centuries of exile, is still so strong that it can still raise five million fighting men, ready to take possession of the Promised Land once again. “

— Franz Liszt, The Gipsy in Music, 1859.2

I get chills every time I read it.

Texts like Lizst and the Lexikon remind us of the dangers of mass movements and their intolerant quest for cultural and ideological orthodoxy. Their attacks on music, as Liszt pointed out, anticipate attacks on people. The Lexikon itself was published just one year before the full-scale launch of the Führer’s “final solution.”

Old Nazis thought Jews had neither blood nor soil in the nations of Europe. New ones believe that Jews should have neither blood nor soil among the nations of the world.

Both antisemitic types are mistaken, both about Jews and humanity. Thriving cultures, musically and otherwise, rely heavily on the exchange of ideas with outsiders. This has been the strength of both Israel and America, countries which have thrived as nations of immigrants. The mass movement’s desire for purity and submission is not only a false god, but comes with intolerance and ultimately violence whose dark ends almost always target the Jews.

In the Land of Israel and in the Diaspora, Jews will always have a place and a song. Our pillars of faith, Torah, and peoplehood have allowed us to traverse any soil and transcend the spilling of blood. But will others stand by while that song is drowned out?

As

wrote: “What happens in society tomorrow can be heard on the radio today.”But what you don’t hear will tell you just as much.

Eric Hoffer, The Temper of Our Time (Titusville, NJ: Hopewell Publications, 2008): 22.

For reference, Theodore Herzl was born one year following the publication of this book.

Excellent post, Matt.