First: A Public Kindness Announcement

“How are you doing?”

This is a key phrase not to say to someone in grief.

One should never be discouraged from the good work of reaching out with a kind word or inquiring after someone’s well-being. On the contrary, it is better to reach out than to choose silence.

But such a simple question as “how are you doing?” never has a simple answer. Were one to truly answer it, a floodgate of joys, worries, fears, cares, and concerns would burst forth which could drown the inquirer. So we reduce this multilayered world of emotion within into digestible, solitary words like “good,” “fine, ” and “okay,” relieving our neighbors of the obligation to pry further , to know what truly lies within.

For the only one who knows the fullness of “how we are doing” dwells above, and within, the hearts of all people.

מַה נּאמַר לְפָנֶיךָ יושֵׁב מָרום, וּמַה נְּסַפֵּר לְפָנֶיךָ שׁוכֵן שְׁחָקִים:

הֲלא הַנִּסְתָּרות וְהַנִּגְלות. אַתָּה יודֵעַ:

אַתָּה יודֵעַ רָזֵי עולָם. וְתַעֲלוּמות סִתְרֵי כָל חָי:

אַתָּה חופֵשׂ כָּל חַדְרֵי בָטֶן. רואֶה כְלָיות וָלֵב:

אֵין דָּבָר נֶעְלָם מִמָּךְ. וְאֵין נִסְתָּר מִנֶּגֶד עֵינֶיךָ:“What shall we say before You, Who dwells on high; and what shall we relate to You Who dwells in the heavens? For everything, both hidden and revealed, You know. You know the mysteries of the universe, and the hidden secrets of every individual. You search all our innermost thoughts, and probe our mind and heart. There is nothing hidden from You, and there is nothing concealed from Your sight.”

—From the Yom Kippur Liturgy. Music by Pierre Pinchik, sung beautifully by mentor and friend, Cantor Abe Lubin

Jews are filled with such floods of feelings during these days of war, of mourning lost relatives, of worries about their neighbors, of praying for the safety and return of hostages, of wondering what is wrong with our universities, and of facing the normal, less-to-equally existential problems of child-reading, breadwinning, and community leadership. Not being in a full-time clergy role, I’ve tried to make it my business to call and check in with those who are. The task of personally and professional navigating leadership during this war is so vital, and also an additional burden in an already weighty job.

So whether you’re Jewish or not, please check in with your Jewish friends. If you can, create an emotional ark for them during this time of flood. Don’t ask: “how are you?” Just start by saying: I heard about what’s happening. I’m sorry. I care about you.

Thanks for listening. And now:

From Pogrom to Purim: Profiles in Disorientation and Hope in Jewish Music

Atrocities like the one Hamas perpetrated two weeks ago against thousands of Israelis, including women and children, elderly and infants, are unfortunately not unique in Jewish history. Apt parallels with the inhuman actions of the Nazi Einsatzgruppen (“mobile killing units”) have already been made. I’m really against paralleling anything to Nazis, but after October 7th there was no avoiding this truth.

Yet Jews have dealt with such hatred throughout our history. And somehow they have leaned into their music — to mourn, to remember, and even to heal. What follows are three stories of Jewish music which rose up from a low place, filling the void with hope after the experience of communal tragedy.

I. A Song of Expulsion and Return

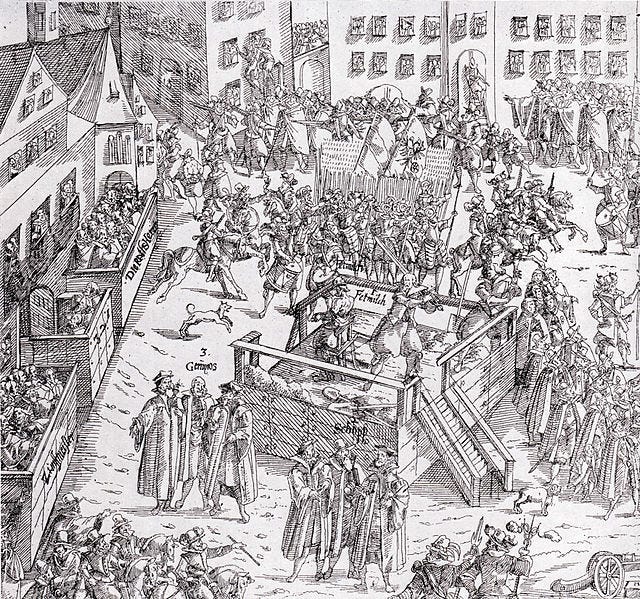

The Fettmilch pogrom in August of 1616, pictured above, led to the pillaging of the entire ghetto of Frankfurt and the expulsion of its Jewish population. The Frankfurt working classes at the time were lamenting the economic stratification of their society, and in an all too familiar story, Jews served as a ready scapegoat. Two years prior to the attack, the ringleader Vincenz Fettmilch had arranged for the publication of a new edition of Martin Luther’s On the Jews and their Lies, which called for: “Jewish synagogues and schools be set on fire, their prayer books destroyed, rabbis forbidden to preach, homes burned, and property and money confiscated,” and justifying murder by saying "[W]e are at fault in not slaying them.”

(Why do all the worst antisemites come out with books telling you what they are going to do first? As

quipped: “when people tell you who they are, believe them.”)Yet this pogrom ended with an eventual redemption. The German emperor sent his troops to Frankfurt and suppressed the rebellion, executing its ringleaders. The Jews were returned to their dwellings the following February. In recognition of this great salvation, the Jews instituted a “Purim Vinz” — a special Purim in honor of the defeat of the antisemitic mob and the restoration of Jewish life to Frankfurt. A yiddish song, the “Vinz Hans lied,” was written to commemorate the occasion, and both its melody and text have come down to us today. You can listen to a shortened version in the video above, or this longer, contemporary recording spoken/sung by Diana Matut and her Germany-based early Jewish music band, Simchat HaNefesh.

II. Migration, Magic, and Rescued Refugees

Another major historical pogrom with musical implications was the Chmielnicki Massacres in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1648-9). Like Fettmilch, the cossack Bodhan Chmielnicki told his populist followers that the Polish authorities had sold them out to the Jews, leading to widespread massacres which left over 100,000 Jews dead. As reported by the eyewitness, Nathan of Hannover in his Yeven Metzula (“Abyss of Despair”):

“Wherever they found the szlachta, royal officials or Jews, they [Cossacks] killed them all, sparing neither women nor children. They pillaged the estates of the Jews and nobles, burned churches and killed their priests, leaving nothing whole. It was a rare individual in those days who had not soaked his hands in blood.”

I wish, with all my heart, that I could have been like one of the cantorial superheroes of that terrible age.

His name was Hirsch of Zviotov, and his contemporary Rabbi Selig Margolis of Kalisch reported that Hirsch’s emotional chanting of the memorial prayer "El Male Rachamim" moved the Muslim Tartars to save three thousand Jews from their deaths at the hands of the cossacks.

Think about it. He sang his community’s own memorial prayer prior to their death — and they were saved because of his song. How can one even make space in one’s heart for such a thing? It is a legend of almost unspeakable pathos. Perhaps it teaches us how open-hearted song powerfully calls forth compassion and our shared humanity, even in the most inhuman moments of human life.

I wish that my chant could save lives like that. Those of us who pray often believe that they can.

This is perhaps partly because music is also magical to the core. In a way, the reciting of blessings are one of the last permitted forms of Jewish magic. For if God is the source of blessing (me’ein hab’rachot), how can we human beings bless him? My gut tells me that blessing and chant is therefore one of the last forms of magic to which Judaism entrusted human beings. Maybe even enough to save a life.

I’ll write more about music and magic at another time. The main point is: like Hirsch’s powerful saving song, our words and our prayers matter. Maybe each one of us has a song of salvation just waiting to come out.

Yet the coda to this horrible age of pogroms is also an uplifting one, filled with both musical innovation and Jewish solidarity. For in the wake of the Chmielnicki massacres, Ashkenazic Jewish refugees went all over the world searching for safer and more prosperous societies in which to live. This created a huge Polish (and later Bohemian) Jewish migration into Western Europe, causing a cultural foment which reformed the traditions of the Western/German-Ashkenazic Jews into those familiar to us to today.1

But even more inspiring is that the entire Jewish world worked together to address this global problem. They housed and re-house refugees. They redeemed captives. They fed, clothed, and cared for their people as they resettled all over the globe. This inspiring work is amazingly documented in Adam Teller’s recent book, Rescue the Surviving Souls: The Great Jewish Refugee Crisis of the Seventeenth Century (Princeton University Press, 2020). Teller wrote the book in order to be a historical reflection which might inform how deal with refugee crises in our own age. But there are also inspiring parallels with how Jews in Israel and abroad are working together today in mutual support and solidarity during this time of trouble.

III. Musical Mourning & Choral Solidarity

This final musical vignette is not a pogrom per se, but rather a tragic shooting during which Jews had come together with non-Jews to fight for human rights and freedoms.

Heard of Les Misérables? Well, political violence and struggles against the ruling class went beyond Victor Hugo’s Paris, extending to many other European cities. The Austrian city of Vienna had its own version in 1848, known as the Märzrevolution (March revolution), which involved a popular, nationalistic uprising against the Chancellor Klemenz von Metternich’s unfavorable economy and his anti-Enlightenment restrictions on free press and free assembly. Cantor Salomon Sulzer, the “father of the modern cantorate” and then Chief Cantor of the Viennese Jewish community, found himself in the middle of this political maelstrom, writing nationalistic anthems for revolutionary students and even allegedly getting into a scuffle with a policeman while holding a pretzel (you just can’t make this stuff up).2 The revolution came to a climax on March 13th, 1848, when the Austrian military tried to break up a demonstration and fired into the crowd, killing five people (including one Spitzer, a Jew). Responding to this tragedy, Cantor Sulzer went with the citizens of Vienna, Jew and Catholic alike, to the Schmelzer cemetery to pay their respects. The piece by Sulzer pictured below, Klaget, Klaget (“Lament, Lament”) has long been thought to be associated with this tragic event.

Here’s one verse that I put together a number of years ago (back when the “A Cappella” app and “collabs” were big). If you can forgive the distortion and timing problems (the limits of my amateur efforts with this technology), you’ll get a sense of Sulzer’s brooding, Brahmsian ode to our holy, fallen brethren.

Here, Jew and Catholic joined together to mourn and to pledge their mutual solidarity. At the time, “Professor” Sulzer had just finished his post as director of the men’s choir at the Vienna Conservatory, where he served from 1842-1847. The title page to Klaget, Klaget says that it was “sung by the grave of the fallen heroic brethren, by the Vienna Men’s Choral Society [Männergesangs-Verein].” This ensemble was founded just a five years prior, likely with the support of Professor Sulzer himself.3 I hope that now, as then, we can come together to mourn and to sing.

~~~

The plight of the Jew is knowing that history, even tragically, repeats itself. We’ve experienced these beautiful and painful cycles for four thousand years. Yet we also know that gam ze ya’avor — that this too shall pass, that one day we will write songs about our foes and haters, and even make up silly holidays about them. The story of our suffering this exists alongside the redemptive story of our music. This reminds us that our song and strength are always rising up amidst our faith, our solidarity, and from our global affirmation of human dignity and love.

It’s a long road ahead. But our songs, as always, will be ready.

This is one of the subjects of my current PhD research.

This story is apocryphal, and is only mentioned in one source. A simple check of the Viennese state police records during the early months of 1848 should lead to a fruitful resolution of this question. I’ll have to wait on this till I write a book about Sulzer (b’’h).

This ensemble is still active today. http://www.wmgv.at/

Magnific learning in honor of the blessed memory of all our ancestors.

Kol Hakavod.