Thanksgiving in our family is pure ritual: a full twelve-hour day of Turkey preparation, cooking, kibbitzing, table-setting, and fall-flavored festive dining. But while the kitchen mavens tuck, tie, stuff, baste, and cook for the grand banquet, another equally ritualized offering blares from the next room: The Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.

In our age of instant digital gratification, the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade endures as one of the last American rites of communal television to survive the rise of streaming, together with the Super Bowl. Just like a religious service, you can watch it later, but it’s just not the same as watching it live.

For our family, the parade is an opportunity to feel the joy, see the stars, and glimpse a glamorous snapshot of America’s musical talent. Like good yekkes, we begin right on time and have it on for hours. Admittedly, we often skip the last ten minutes and the long-awaited arrival of Santa Class, because that’s not the point. The parade is there to show America on display, in song, and counting its blessings.

Thank you for reading Beyond the Music! If you enjoy reading this newsletter, please consider supporting me with a paid subscription.

This week, the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade also turns one hundred years old. The inaugural parade in 1924 (known as “The Macy’s Christmas Parade”) featured horse-drawn floats, circus acts, marching bands, and animals from the Central Park Zoo. This tremendous pageant was put on by the store’s immigrant and first-generation employees, who brought their European tradition of parades to the streets of New York.

So to count the blessings of the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade, and to explore the meaning of this form of public spectacle, I’m going to serve up two untraditional slices of European parade history — Jewish and Christian—with a side of savory relevance for today.

I. What Have the Romans Ever Done for Us?

Although I don’t think about it every day, the Roman Empire created one of the most iconic forms of parade to come down through the ages: the Triumph. In ancient Rome, this religious procession celebrated the success of a successful military commander. The victorious leader would wear purple as a sign of his near-divinity, lead a long, festive procession with his army and spoils of war, and conclude with a sacrifice to the gods.

This tradition suffused ancient Roman culture, and comes down to us through the familiar architectural form erected to commemorate such occasions: the triumphal arch. Many of these are scattered throughout the West as memorials to great victories: the Arch of Titus in Rome, the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, Wellington’s Arch in London, and even the Washington Arch in Greenwich Village.

In between the Roman Empire and the Romantics, the tradition of the triumph experienced its greatest revival during the Renaissance, when society again looked to the classical past for inspiration. Early modern monarchs often threw triumphs to project their power and cultural achievement, and artists kept the motif alive in their classical subjects. And the triumphal arch, if only a temporary one, remained an integral part of the culture of Renaissance and Baroque parades.

The Jews of Europe were not blind to these motifs and forms of political theater. In fact, a few large communities were able to co-opt them for themselves.

So without further ado, let me present to you the Jews of Prague’s Old Town in the Emperor’s Day Parade.

II. Happy Birthday, Dear Habsburg!

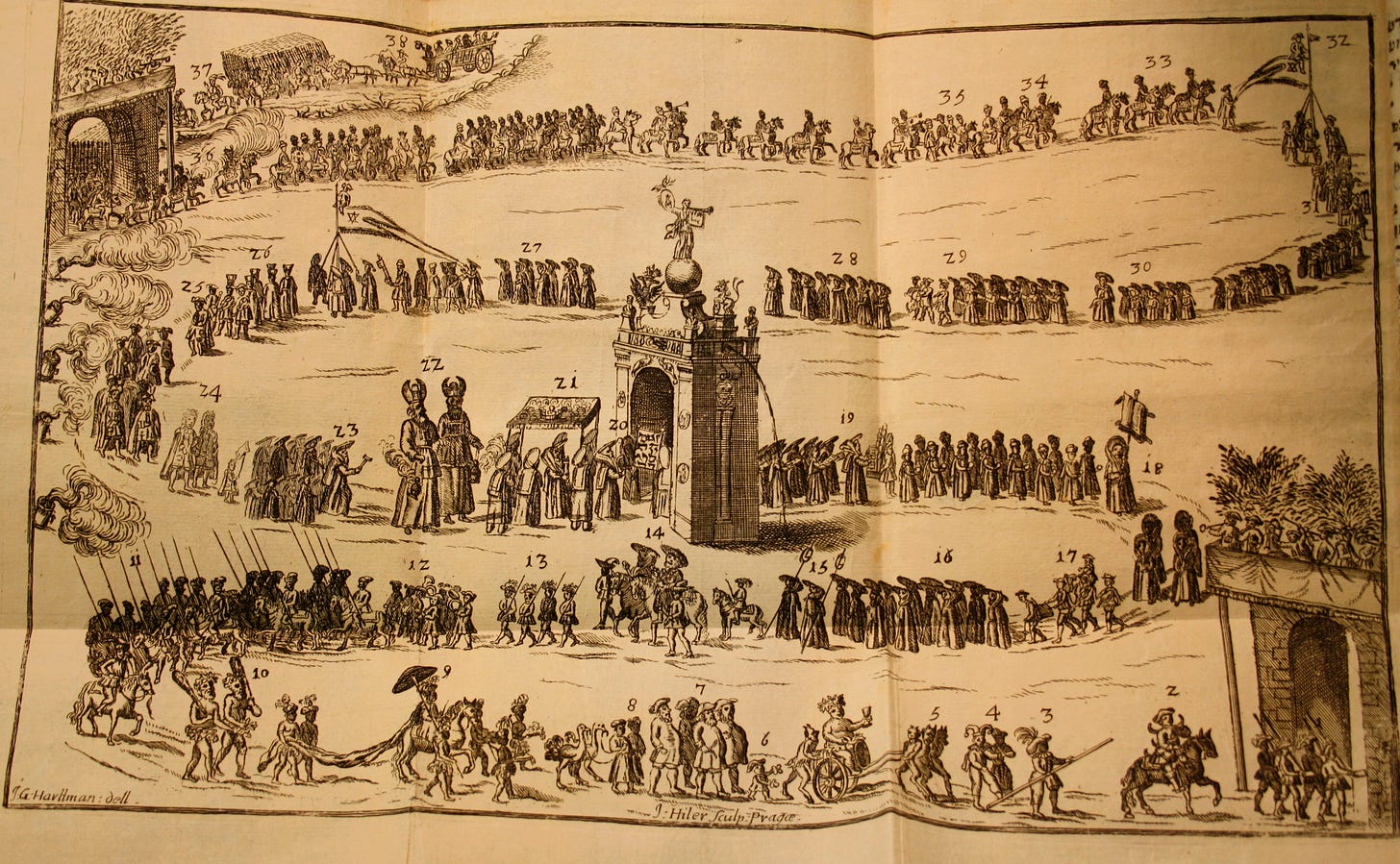

On May 18, 1716, the Jewish community of Prague came together on Broad Street to celebrate the birth of a new heir to the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles VI. This was not a new phenomenon; the Jews had put on a parade like this several decades prior at the birth of Emperor Leopold’s eldest son and heir, Joseph.

If this parade looks like a big deal, that’s because it was. Although a parallel Jewish parade was held in the sister imperial city of Frankfurt-am-Main, nothing could top the scale of Prague. At over ten-thousand strong—a full quarter of the city’s population— Prague boasted the largest urban Jewish population in Christian Europe. To put it another way, it was the NYC of European Jewry.

The parade was a carnivalesque tour-de-force. Dartmouth Professor Rachel L. Greenblatt walks us through the amazing scene:

“On May 18, they staged an elaborate baroque procession within the confines of the Jewish Town. It included a Bacchus with his satyrs, oversized versions of biblical Aaron and Moses, musicians playing portable instruments, students, teachers, doctors, lawyers, and more. Two separate banners of the Prague Jewish community, each approximately eight feet tall and eighteen feet long, were carried by members of the kosher butchers’ guild, with a small child riding atop the banner’s central supporting pole. At the center of the procession was a man carrying two tablets of the law under a decorative baldachin, a long-standing motif in Prague Jewish royal procession…the procession, in other words, encompassed within it all the complexity inherent in Jewish participation in central European cultural forms—be they linguistic, artistic, or musical— that built on both classical and Christian artistic traditions.”1

This event gives Macy’s a run for its money. A full complement of Jewish guilds, musical professionals (including cantors), and even float-sized mythical characters are on display from this sophisticated and confident Jewish community. They even do a Latin gematria trick (!) to commemorate the year.2 And of course, there’s a triumphal arch built for the occasion.

The arch is festooned with decorations and blaring music, with a full complement of klezmer musicians on the parapet and a precariously-placed horn player at the very top. Professor Greenblatt points out that this procession was royal-grade, as Prague’s Jews demonstrated their competence in Baroque culture (and even German language) in order to enact their claim to cultural belonging in the Habsburg Empire. As typical for such festivals, a number of commemorative booklets were printed to record the spectacle for posterity (hence the small numerical labels on the pictures themselves, which correspond to numbered records in the booklets describing each station of the parade).

Fortunately, for the musically-minded among us, one of these booklets notated a piece of parade music — a German processional aria composed by Isaac Bass, in sixty-three verses, accompanied by musical instruments. You can hear a snatch of it sung below by my colleague, Ian Pomerantz.

III. March, Sing, and Be Thankful

The Prague Jewish Parade of 1716 enthralls me to this day. The amount of full civic participation is incredible, and the illustration conveys the joy and bravado of a fiercely proud Jewish community. Because of their patronage and overall protection by the rule of law, these Jews prospered and could march in the street in ways that their ancestors a century-and-a-half prior could never dream. Only this later era of law, cultural exchange, and relative peace could render the stunning words of gratitude and song below, penned by a cantorial elder statesman in a small Bohemian town just a few years following the parade:3

In North Africa and the Lands of Ishmael, The nations forbid us to pray with a wail; But as for us, we, thank God, have a king of love and mercy; may God lengthen his days and years with pleasantry; Him, his wife, and his seed 'till generation's end; for he has always been our friend! So we have permission to pray as our souls move us: Loudly, and with music too, And no one complains or gives reproof. Even the princes and governors under whom we dwell -- May God lengthen their days and their years -- treat us well.

Time passes, and new pharaohs arise. Charles VI was succeeded as ruler of Bohemia by the Empress Maria Theresa (1740-1780), who expelled the Jews from Prague with aims to rid them from her lands entirely. Yet political pressure arose — from home and abroad, from Jews and their allies, and from local nobles and international bodies, to allow the Jewish community of Bohemia to once again have safe harbor. Under such protest, the Empress ultimately rescinded her edict, and within a decade the Jewish community was allowed to reform and begin again.

The joy of a parade captures our human vitality, whether on the battlefield or in the public square. When we watch the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade on Thursday, we should be reminded of that aliveness. And that it takes an equally joyful and purpose-driven parade of people to keep it going.

Bari Weiss recently quipped that the old world is not coming back. So many tragedies, large and small, chip away at the security, confidence, and the outwardness of many Jews. But as Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik taught, we are a people of destiny, not a people of fate. The response to such suffering is so often not the question of why, but of how we shall respond: “How pitiful is the sufferer if his soul is not warmed by the flame of suffering, and if his wounds do not spark ‘the Candle of God’ within him.”

If you watch the Thanksgiving Day Parade this week, I hope it reminds you to be shaken up with the joy of Jewish pride. Our ancestors did not shirk from such grandiose displays, proudly marching in silliness and pomp, with confidence in their place in society and their great destiny. And when that was threatened, they were undeterred to roll up their sleeves worldwide to restore the norms of flourishing Jewish life.

Rachel L. Greenblatt, “A Jewish Easter Lamb: Cultural Connection and Its Limits in a 1716 Prague Procession,” Connecting Histories, Ed. Francesca Bregoli and David B. Ruderman (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019): 154-155. Rachel has also written another excellent article about thes parades in Prague in Frankfurt: “On Jewish Prague in the Age of Schudt’s Frankfurt: Two Jewish Towns in Celebration on the Birth of an Heir to the Habsburg Throne (1716)” Frankfurt Jewish Studies Bulletin, Vol. 40 (2015): 239-257.

R. Yoel b. Eliezer Sirkis, Reiach Nichoach (Fürth: 1724), published in my masters thesis (2011). R. Yoel was married in Kolín to a cantor’s daughter in the mid-late seventeenth century and served as cantor in Česká Lípa, north of Prague, for his whole career.

Here is the original Hebrew of the above passage, whose for the original poetic effect (lines 109-118):

ובארץ ישמעאל ואפריקה/ האומות אינם מניחין להתפלל בקול צעקה/ אבל אנו יש לנו ת”ל מלך חסד ורחמי׳/ השם יאריך לו ושנותיו בנעימי׳/ הוא ואשתו וזרעו עד סוף כל הדורות/ אשר תמיד הוא מיטיב לנו ויש לנו רשות להתפלל כאות נפשינו/ בקול רם ונגינה/ ואין פוצה פה ואין עונה/ וגם השרי׳ והמושלי׳ אשר אנחנו יושבי׳ תחתיהם/ מטיבי׳ לנו השם יאריך ימיהם ושנותיהם