Instead of “Happy New Year,” this week consider offering your Christian friends this alternative greeting: “A freylikhn mazl tov oyfn Yoshke's bris!”

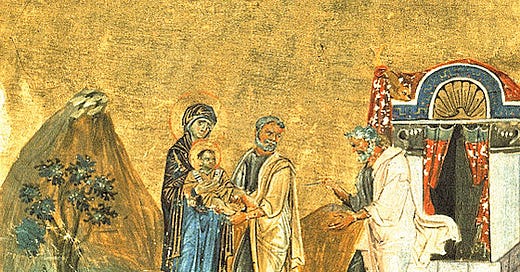

That’s because for Eastern Orthodox Christians, Lutherans, and some Anglicans, Wednesday is also known as the Feast of the Circumcision, celebrating the day on which Jesus of Nazareth, a Jewish boy, was brought into the covenant of Abraham (Catholics also celebrate this on Friday as the Feast of the Holy Name). As it says in the Book of Luke (2:21): “When the eighth day came, it was time to circumcise the child, and he was called Jesus, the name given by the angel before he was conceived in the womb.”

This makes Jesus the only Jew with over a billion people still celebrating his bris. Good thing they didn’t have slides back then. Although they did have relics, and many people still believe that they might have the most peculiar of souvenirs.

Jews have spent the better part of two-thousand years trying to keep theological daylight between themselves and the big J.C. But because of a spate of revisionism attempting to de-Judaize Mary’s miracle child, I’m compelled to throw some cold historical water over our collective faces to wake up to the basic fact of Jesus’ thoroughly Jewish birth and childhood.

Thank you for reading Beyond the Music! If you enjoy reading this newsletter, please consider supporting me with a paid subscription.

When I was in cantorial school, we learned that one of the earliest sources of the Prophets (haftarah) being read as part of a Shabbat service is the report in the Book of Luke (4:16-21) of Jesus of Nazareth’s reading at the Temple. And of course, so many of the big guy’s greatest hits (like “love your neighbor as yourself”) are taken straight out of the Scripture he knew best — the Hebrew Bible (Lev. 19:18; Deut. 6:5).

My wife knows this better than me. A rabbi with an MTS from a Methodist seminary, she once did peer-guided text study on a Hebrew version of the New Testament. And when you read the Gospels in Hebrew, Jesus’ biblical quotations just jump off the page.1 So for whatever my theological differences with the guy, at least he was paying attention in Hebrew school.

But let’s get back to the bris. This feast day has music of its own. And you don’t have to go farther than J.S. Bach for a good start. Before his well-known Christmas Oratorio (BWV 248) was a concert piece, it comprised six separate cantatas purposed for different feasts across the twelve days of Christmas. The fourth cantata, Fallt mit Danken, fallt mit Loben, was premiered at the morning service on New Years Day, 1735 at the St. Nicholas Church in Leipzig. Here’s the evangelist announcing the big event:

Jesus of Nazareth’s circumcision, of course, contains many other layers of meaning in Christianity. Many of its theologies focus on the shedding of blood as a harbinger of the messiah-man’s later self-sacrifice, rather than as a biblical initiation rite into the covenant of Israel. You can read the simple lyrics of this Anglican hymn for the Feast of the Holy Name to get the alternate focus that this lifecycle event takes on in the Christian story.2

Wednesday’s little-known feast may be the most celebrated Jewish circumcision in the world. Yet where Christianity, to my knowledge, formally celebrates just one of these special occasions, Jews have continued to celebrate the brit milah for millennia before and after. We may not have J.S. Bach for the soundtrack, but we do have our own diverse music traditions for this ancient rite.3

In this department, Sephardic Jews have a wonderful repertoire of Judeo-Spanish songs which tell Jewish stories to celebrate the miracle of birth and covenant. This includes the famous “Cuando El Rey Nimrod” which has made it outside the circumcision ceremony as a widely popular Jewish tune. While we usually only sing part of it, the full song is a high religious drama. It weaves together legends about the biblical King Nimrod, who seeks to kill baby Abraham after seeing a sign of his imminent birth. Abraham’s mother gives birth secretly in a cave, and the newborn comforts her with his immediate faith. King Nimrod learns of baby Abraham and brings him to make an example of him, yet baby Abraham performs a miracle of passing through a fire, after which he is freed. This dramatic narrative gives the circumcision ceremony new meaning as parallel to that divinely-accompanied journey of faith taken by the first Jew:

Great merit has honorable Abraham Because of him we recognize the true God. Great merit has the father of the newborn Who fulfills the commandment of Abraham our father (circumcision). We greet now the father of the newborn We wish this newborn has been born under a good sign (siman tov). Because Elijah the Prophet appeared to us And we will give praises to the True One.

Some astute readers will notice the influence of Christian stories on this legend. King Nimrod and King Herod are parallel figures who seek to kill a subversive monotheist in their midst after hearing of his impending birth. And the whole talking newborn thing? Likely from Islamic legends about the speaking infant Jesus. This goes to show that even in celebrating a particularistic religious event, we cannot help but draw water from the deeper well of human stories which exist in our own multi-confessional society.

And this goes both ways. Just as Jewish ears were open to their neighbors, so too were Christian ears open to the sounds of the Jews. In fact, the sound of Jews welcoming a baby into the Abrahamic covenant was so frequent in Italy that it was incorporated into the classical music tradition.

Italian composers during the Renaissance created a number of ebraiche (“Jew songs”) which satirically depicted their semitic neighbors. They’re not very nice, but hear me out: One of the most common nonsense Hebrew words in these songs is “barucaba” — a faux-Italian version of the Hebrew baruch ha-ba (“Blessed is He Who Comes!”) which is cried out by the whole community (and, in Renaissance Italy, at the door of the synagogue) at the opening of the circumcision ceremony.

You can hear it in this song by Adriano Banchieri (1568-1634) from his comedy madrigal, Barca di Venetia per Padova (“The Boat from Venice to Padua,” 1605). This scene depicting Jewish prayer as noise particularly highlights the word barucaba, as Don Harrán describes it, as an emblem of Jewishness.

But the cultural meme of barucaba did not end there. The melody “La [si]gnora Luna” (“Lady Luna”), a popular street song about a Jewish character Barucaba and his wife, became ubiquitous in the late eighteenth century and was eventually the subject of a piece of music by the composer, Antonio Paganini (1782-1840). Don Harrán’s excellent scholarship reveals that Paganini would not have known this song as a Genoese air, but “as an aria no less emblematic of the Jews in their speech, music, and customs than the term itself in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century ebraiche.” So on the eve of Jewish emancipation in Italy, Paganini enshrined the welcoming words of the circumcision ceremony in a virtuosic series of variations for violin.

With Wednesday’s mega-convergence of the secular new year, the Jewish new month, the Feast of the Circumcision, and the last night of Hanukkah, it’s a good time for rededication. And on this front, there’s more to be shared than just music.

As Liel Liebowitz penned this past week:

“What’s essential now is what has always been: God and love, parents and children and friends, charity and kindness, service and sacrifice—all the good stuff our religious traditions have cherished and promoted for millennia. Want to make sure we win the battle for America? Here’s my plan: Just do one more thing this week that truly reflects the wisdom of your faith tradition than you did last week. Do that, and you’ll discover that religious observance is not only rewarding, but also the world’s greatest source of renewable spiritual energy.”

So mazel tov to the baby in the manger, and to all the other babies entering into families and covenants in the year to come.

And to those looking to the year ahead, ready to rededicate themselves to a “radically bright and cheerful future,” we say baruch haba.

Welcome.

Interestingly, some modern Hebrew editions of the New Testament put Hebrew Bible quotations in red, rather than the words of Jesus of Nazareth as is traditional in Christian bibles. This very conscious move is likely to alert potential Israeli converts to biblical source texts, which are taught widely in Israeli public education.

My thanks to fellow writer Mackenzie France for introducing me to this hymn and for reading a draft of this article.

For history of medieval and early modern Ashkenazic musical traditions relating to circumcision, see this excellent article by Geoffrey Goldberg.

@Evan Goldfine of course your pick for BWV 248 was my go-to recording.