Situated in the dark of winter, this week of Hanukkah is all about light. Jews worldwide are enjoined to “publicize the miracle” of Hanukkah by placing the candle-filled Hanukkah menorah (hanukiyah) in their window, gates, or other public places. The rabbis of the Talmud developed this custom as a remembrance of the miracle of the oil which unexpectedly lasted for eight nights. My rabbi growing up even once made the case that this festival of lights was a subconscious form of Jewish communal therapy for Seasonal Affective Disorder.

But of course none of this is the full story. Especially not this year.

Ma Nishtana HaHanukkah HaZot? What is different about this year’s Hanukkah is that its manifestly political overtones are unavoidable. Typical years are filled with pithy yet worthy slogans like “be proud to be Jewish” and “spread light in the world.” This Hanukkah, the war of the Maccabees and the contemporary war against Hamas seem to collapse together in time. These are of course profoundly different conflicts, but both are staked in the rights of Jews to safety and religious freedom — both inside and outside of Israel.

Of course conflating holidays and geopolitics goes both ways. An arts festival in my old college town of Williamsburg, for example, recently got in hot water for denying a local Jewish group’s request to host a menorah lighting. Their policy is to reject requests for all religious events, but the organizers made the mistake of sharing the board’s motivations:” We are about Peace, Love & light....[we] don’t want to make it seem [as if we were] choosing a side.”

A bevy of Virginia politicians (including the governor) piled on to condemn the festival, maintaining that “holding Jewish people responsible for the ongoing conflict in the Middle East is shocking and outrageous.” Thus the narrative of Hanukkah, while religiously meaningful for Jews, also seems to come with the conflation of the Maccabees and the Israelis, giving way to pearl-clutching antisemitism on Duke of Gloucester Street.1

Our religious freedom can and should not be dependent on geopolitics — for it is exactly that which led to the Hellenists' oppression of the Jews in the first place. America does not restrict a Russian Orthodox Christmas celebration over the war in Ukraine, or a public celebration of Ramadan because of Hamas’ barbarism, or cancel the Chinese New Year because of their CCCP’s repression of Uyghur Muslims. On the complete opposite side of the moral pendulum stand the Israelis, fighting a just war against the most inhuman of opponents.

Yet the rabbis of the Talmud were also uncomfortable centering a war – even a just war – in Jewish life. As Rabbi Avital Hochstein wisely teaches, war leads to painful choices that can bring out conflicts in our values, and can even risk us losing sight of the type of community we really want to create. And the rabbis also understood that all too well as the descendants of the Maccabean victors, the Hasmoneans, fell tragically into corruption. So rather than traffic in these messy politics, the rabbis chose to focus on the light, within and without.

This is a beautiful, important spiritual message. I long for a day where the Maccabean war feels alien to the peaceful spirit of our age, and the great ideals of our rabbinic tradition are in bloom.

But that is not this year. This year, we watch Maccabees on the news, and listen for the echoes of their victory.

In recognition of this paradox, this week I will share two vignettes about the political import of the Hanukkah story — both past and present. The first is an obscure law of religious freedom with a two-thousand year shelf-life; the second, the tale of a formerly unsung heroine getting a new Hanukkah opera.

I. The Edict of Privileges: A Tale of Two Antiochuses

Hanukkah is often depicted (and quite rightfully) as about religious freedom. What is less known is that the Maccabean revolt was the first war of religious freedom based on legal precedent.

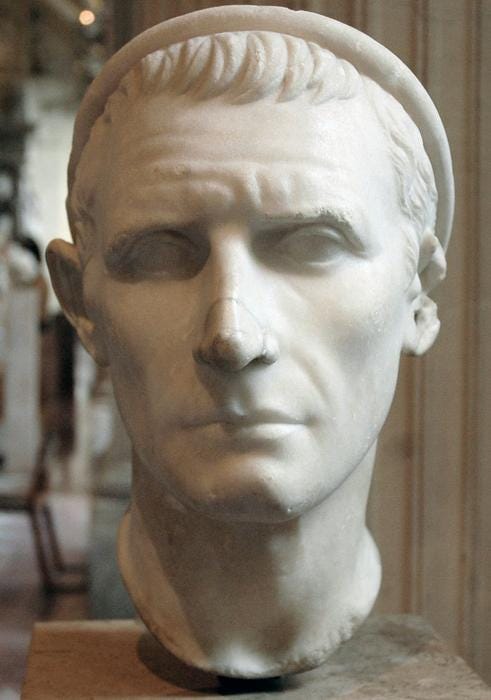

In 200 BCE, the Seleucid King Antiochus III (known as “Antiochus the Great”) took over the land of Judea after defeating the army of Ptolemy V, whose rival empire was based in Egypt. In gratitude for their support in this conflict, Antiochus the Great granted the Jews of Judea the right of religious self-determination in what became known as the “Edict of Privileges.” You can read the full text here, translated from Josephus’ Antiquities.2

Then, like the Torah’s new pharaoh who did not know Joseph, problems arose under the next king, Antiochus IV, who became the villain of the Hanukkah story. Thus the Maccabean revolt against Antiochus IV’s suppression of Jewish life was not only launched on a religious basis, but on the legal norms established under the previous administration. Because of the Maccabean victory, these norms continued. Indeed, such Jewish communal self-determination in the diaspora would remain for the next two thousand years.

This is important not just for its historical precedent. It is also an important reminder of the precious nature of religious freedom as enshrined in law — especially important as Jewish religious expression today is sought to be suppressed by overt and covert antisemites.

But the consequences of Hanukkah goes even deeper. For all the talk of it being a minor liturgical holiday, the true result of it was that Judaism absorbed Hellenism rather than the other way around. This preserved Judaism, and ultimately the later founding of Christianity, which would spread Hebrew scriptures around the world. Such monotheistic developments could only be realized in a Jewishly-rooted, post-Maccabean world.

Finally, the above history is also a good reminder that Jews can never jettison their host culture -- the question is who is in the driver's seat. The Maccabees created a holiday based on a military victory -- a very Greek thing to do, which is partially why the rabbis focused on the miracle of the oil. But the Maccabeean victory definitively made sure that Judaism stayed in the cultural driver's seat through an era of inevitable change.3

II. Judith — The Book and the Opera

Ever heard of the Book of Judith? While a Jewish book, usually you will find more Catholics are familiar with it than Jews. That is because it, like the Book of Maccabees, was included in the Apocrypha, but not in the Hebrew Bible.

We’ll explore the reasons for this, but let’s start with a summary of the book:

King Nebuchadnezzar of Assyria is on the warpath, and the Jews are resisting. His general, Holofernes, lays siege with his troops to the town of Bethulia. Water supplies run low, and the people press their leaders to surrender. Then comes the heroine – a pious, beautiful widow named Judith, who reprimands Bethulia’s leaders for their lack of faith. She and her maid then sally forth on a spy mission to Assyrian camp, where she charms their general, Holofernes, and promises to help deliver Bethulia into his hands. He invites her to a party with the hope of seduction, yet gets too drunk and passes out. Judith then decapitates the sloshed soldier and smuggles herself (and his head) back to Bethulia. With surprise on their side, the Jews go on the offensive and defeat the panicked Assyrians. Judith sings a victory song, and lives out her life until the age of 105, celebrated by her people.

Interesting, right? So how could the Israelites possibly have not included such a corker as holy writ?

The Book of Judith is a late book, written down in Greek after 150 BCE. Even though the book was sidelined from Talmudic literature, it re-emerged in the medieval era in Jewish legal works, talmudic commentaries, and liturgical poems. During this period, the story began to become associated with Hanukkah as new variants of the story emerged, some of them replacing the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar with the Seleucid King Antiochus IV. There’s even a 15th century Megillat Yehudit, a Scroll of Judith, developed for liturgical use on the holiday.

And guess what? It just got a new opera.

Last week, fifth-year cantorial student Iris Karlin premiered her new composition, “Yehudit: A Modern Hazzanut Opera” at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in New York, accompanied by an orchestra, cantorial students, and the talented faculty of the Debbie Friedman School of Sacred Music. The opera’s purpose is to “bring Yehudit’s voice and heroic deeds out of historical obscurity. Adding another thread to the tapestry of Jewish women whose story must be told.” Karlin’s opera especially focuses on Yehudit’s heroism in empowering women’s voices and protecting their bodies. This reading of Judith relates strongly to its medieval interpretations (including Megillat Yehudit), which accused the invading Assyrians of practicing ius primae noctis — the practice of nobles taking sexual advantage of women before they are married.

Karlin’s soaring symphony of women’s empowerment and equality could not come a measure too soon. In the wake of Hamas’ unspeakable crimes of sexual violence and the allegations that warnings about October 7th were dismissed by the IDF because they came from an all-female unit, the disastrous consequences of the minimization and dehumanization of women have once again been made excruciatingly clear.4

The libretto written by Karlin is a sophisticated, multi-pronged musical paean to female agency in the face of stereotype, shame, and gaslighting male leadership. Her opera’s storytelling, which weaves together many layers of rabbinic tradition, re-animates the figure of Yehudit as a mythical archetype for female power, matched by Karlin’s own vocal agility and passion for the role.

One should also give huge credit to the 40+ member ensemble who mounted this production. I give a lot of credit to the students (busy in their own right), but also to the dedication of the DFSSM faculty and local cantors who participated in the production. It is so clear that these faculty and colleagues have the backs of their students, and it’s a real blessing to watch on stage.

So why is it that Judith has had so little stage time from the middle ages until today? Like the Book of Maccabees, the story of Judith is one of war, power, and human heroism. The rabbis wanted to create a post-Temple religion that focused on internal strength, rather than external strength — on God’s power rather than ours. And so the tales of Judah (Maccabee) and Judith took a back seat.

There is great wisdom in this rabbinic approach. But in this time of war and fighting for our values, now is the moment to return Judith to her place in the spotlight.

The College of William & Mary, my alma mater, ended up hosting the menorah lighting.

My wife wittily observed that this is also the first precedent for parsonage in the tax code.

I share the above teaching in the name of my teacher, Rabbi Hillel Millgram, who first taught me this perspective on the importance of the Maccabean revolt.

This view is consistent with the thrust of the Book of Judges, in which the moral decay of the Israelites corresponds directly with the loss of women’s names and agency, culminating in violence against them. For more on this, see Hillel I. Millgram, Judges and Saviors, Deborah and Samson: Reflections of a World in Chaos.