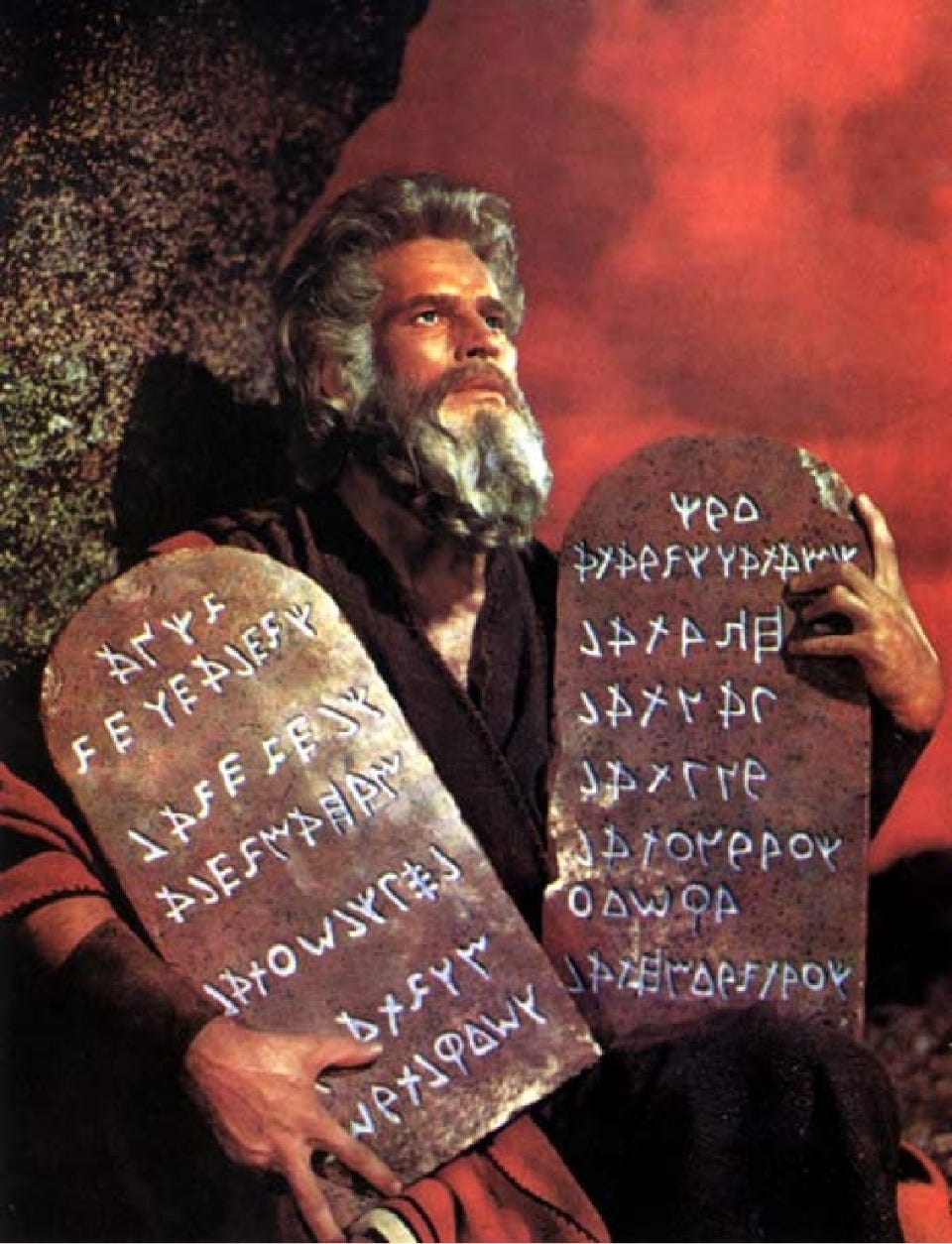

This very evening, the shadow of Mount Sinai looms large over the Jewish people as they furtively prepare their souls (and their cheesecakes) to celebrate the receiving of the Torah.1 Biblical cinema from Cecil B. DeMille to Mel Brooks marks this moment as a scene of epic proportions, casting towering rocky peaks in the role of Mount Sinai.

Yet to Jews, Sinai was no Everest. In fact, the Talmud teaches that it was the humblest of hills (Babylonian Talmud Sota 5a):

“Rabbi Yosef says: A person should always learn proper behavior from the wisdom of his Creator, as the Holy One, Blessed be He, disregarded all of the mountains and hills and rested His Divine Presence on the lowly Mount Sinai. And similarly, when appearing to Moses, He disregarded all of the beautiful trees and rested His Divine Presence on the bush.”

When speaking great words, the God of the Hebrew Bible does not take to the grandest stage or the highest heights. Like a parent kneeling down to lock eyes with their child, one must often descend in order to be a good teacher.

The city of Jerusalem lies on a plateau in the Judean Mountains. Like Sinai itself, it sits at a modest elevation, and yet is a summit from which religious teaching and inspiration are ever flowing, both for the Jewish people and for the followers of its Abrahamic daughter-faiths. We often think of the city in newsworthy terms, both religious and political. But what of Jerusalem as a “city of music?”

This very idea rendered the title of a book by the Israeli musicologist Meir Shim’on Geshuri: Yerushalayim Ir HaMusikah — Jerusalem: The City of Music. Written to commemorate the city’s three-thousand-year-jubilee, Geshuri’s book also sought to recreate the musical world of Jerusalem during the Second Temple period. Zionist thinkers have long looked to Hebraic antiquity for models of national statecraft—but what about music? In pursuing his research, Geshuri sought to redeem a fuller picture of Jerusalem in its ancient musical prosperity, divorced from the religious tendentiousness of Christian historians. Thus he became father to long-orphaned questions, such as those he inscribed: “Were the Jews of the Second Temple period preoccupied with music and song? And were Jews involved in singing, dancing, and the like in personal and communal life?”

Such questions are far from academic, but hint at greater longings for revelation: Does not only Torah come from Zion, but music as well? Those who have lived there know that Jerusalem is bustling with a multiplicity of music, as diverse as the world is wide. Yet the full potential of this vision has once again arisen in the Judean hills through that most mountainous of musical genres — opera.

Samuel Berlad,2 an opera singer and Jewish cantor, made aliyah in 2012 with the hope of building a life and artistic career in Israel, studying with the late great cantorial pedagogue, Naftali Herstik z’’l. Like many musicians, he found work through freelance projects — but over time, the lack of long-term opportunities made it hard to grow, both professionally and personally. When the pandemic hit, he accepted a full-time soloist position in Halberstadt, Germany. It gave him stability, but at a cost. Life as a Jewish artist abroad came with challenges, and in Halberstadt, antisemitism was a constant reality. The decision that was supposed to offer security left him feeling unmoored. It was this experience that made the bigger picture impossible to ignore. His conviction was that artists shouldn’t have to choose between career and identity—between artistic excellence and Jewish life.

In the quiet moments between performances abroad, a powerful dream took shape: What if Israeli opera singers could pursue their passion without leaving home?

This vision emerged from the harsh reality facing Israel's classical vocal talent, a landscape where world-class artists face impossible choices. Many Israeli singers possess extraordinary gifts, having trained at prestigious conservatories and mastered their craft through years of dedicated study. Yet they encounter a professional environment with no permanent ensemble companies, inconsistent performance opportunities, and working conditions often incompatible with religious observance.

The painful result is predictable: a talent exodus.

This powerful dream and harsh reality led Sam and his team to form a new startup: Opera Shalem (www.operashalem.com), a permanent, full professional opera company resident year-round in Jerusalem.

This model, unmatched in the current iterations of the Israeli opera world, seeks to provide stability, cohesion, community connection, and inclusivity that will allow for Israel’s incredible home-grown musical talents to secure steady employment, ongoing communal and musical collaboration, and benefit to Jerusalem’s local culture and tourist economy, all while ensuring that their artists can remain true to their religious and cultural beliefs (a difficulty which I also discovered in my own journey as a religious musician).

Opera Shalem holds promise not only as an artistic center, but also as a vehicle for economic revitalization and cultural diplomacy. The company’s own artistic vision extends beyond the standard repertoire to include works that reflect the diverse cultural traditions of Jerusalem and the broader Middle East. This includes:

Commissioning new operas based on Middle Eastern stories and themes

Incorporating musical elements from untold traditions

Presenting works in Hebrew, Arabic, and other languages relevant to the region

Developing educational programs that engage Jerusalem's diverse communities

Such priorities are in line with the city’s own municipal goals for cultural investment. The Jerusalem Foundation's 2030 strategic plan specifically identifies cultural infrastructure as a priority, and the Israeli Ministry of Culture has signaled increased support for cultural institutions outside Tel Aviv. The Jerusalem Development Authority's "Jerusalem 2030" plan further includes provisions for new cultural venues, recognizing their importance to the city's future development and international positioning.

Jerusalem's identity as a holy city need not preclude its development as a cultural capital. Indeed, throughout history, spiritual centers have often been hubs of artistic innovation and excellence. From the Psalms of David to the intricate mosaics of ancient synagogues and churches, Jerusalem's religious heritage has always been intertwined with artistic expression.

Opera Shalem represents not a departure from Jerusalem's character but an evolution consistent with its historical role as a center of human creativity and expression. By establishing a world-class opera institution in Jerusalem, we fulfill an artistic birthright too long deferred and create a legacy that will enrich generations to come.

To be an artist, like a Jew, is often to live as a wanderer. Yet the Israelites, who wandered in the desert for forty years, ultimately yearned for a settled life where they could one day sit under their vine and fig tree. Today, Opera Shalem seeks to make this possible for Israelis of all backgrounds, once again restoring Jerusalem to its biblical vision as a City of Music. Those with the means should make a donation or consider laying the financial groundwork for this new sacred space for Jerusalem’s musical culture.

In these days of war and pessimism, music reveals hope. Like the gift of Torah, Opera Shalem offers the potential for wholeness for those wandering in the desert, longing for a home and parched for the nourishing arts of peace.

From the lowly hills of Jerusalem, may this be a revelation to us all.

This week’s post comes a day early, in honor of tomorrow’s observance of Shavuot.

The copy included from here until the concluding paragraph is drawn largely from Opera Shalem’s website: www.operashalem.com.