Today, Israel is at war. On Saturday, the festival of Shemini Atzeret (and the secular date of the 50th anniversary of the Yom Kippur War), Hamas terrorists from Gaza infiltrated throughout the South while 5,000 missiles rained down on all over the country. They murdered civilians in the streets, at cars and bus stops, and in their homes. They abducted the elderly, women, and little children. They stripped the bodies of dead Israelis to be taken, beaten, and paraded through Gaza. Jews all over the world are filled with shock, anger, and tears after this vile pogrom.

Such horrifying evil cannot help but recall the biblical story of Amalek: “Remember what Amalek did to you on your journey, after you left Egypt—how, undeterred by fear of God, he surprised you on the march, when you were famished and weary, and cut down all the stragglers in your rear (Deut. 25:17-18).” Amalek’s attack on civilians and the weak show that they have no “fear of God (yir’at elohim)” — a biblical term for basic decency and values shared by all human beings. Once again, such an Amalek has struck from Gaza, and Israel’s army prepares for war.

But fighting Amalekites has not just been the work of the military. Over the last fifteen hundred years of Jewish history, it was the work of the cantor as well.

“And Amalek came and fought with Israel at Rephidim.

Moses said to Joshua, “Pick some troops for us, and go out and do battle with Amalek. Tomorrow I will station myself on the top of the hill, with the rod of God in my hand.”

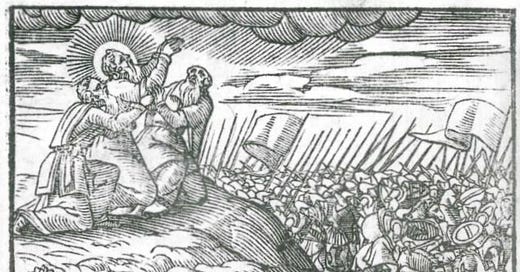

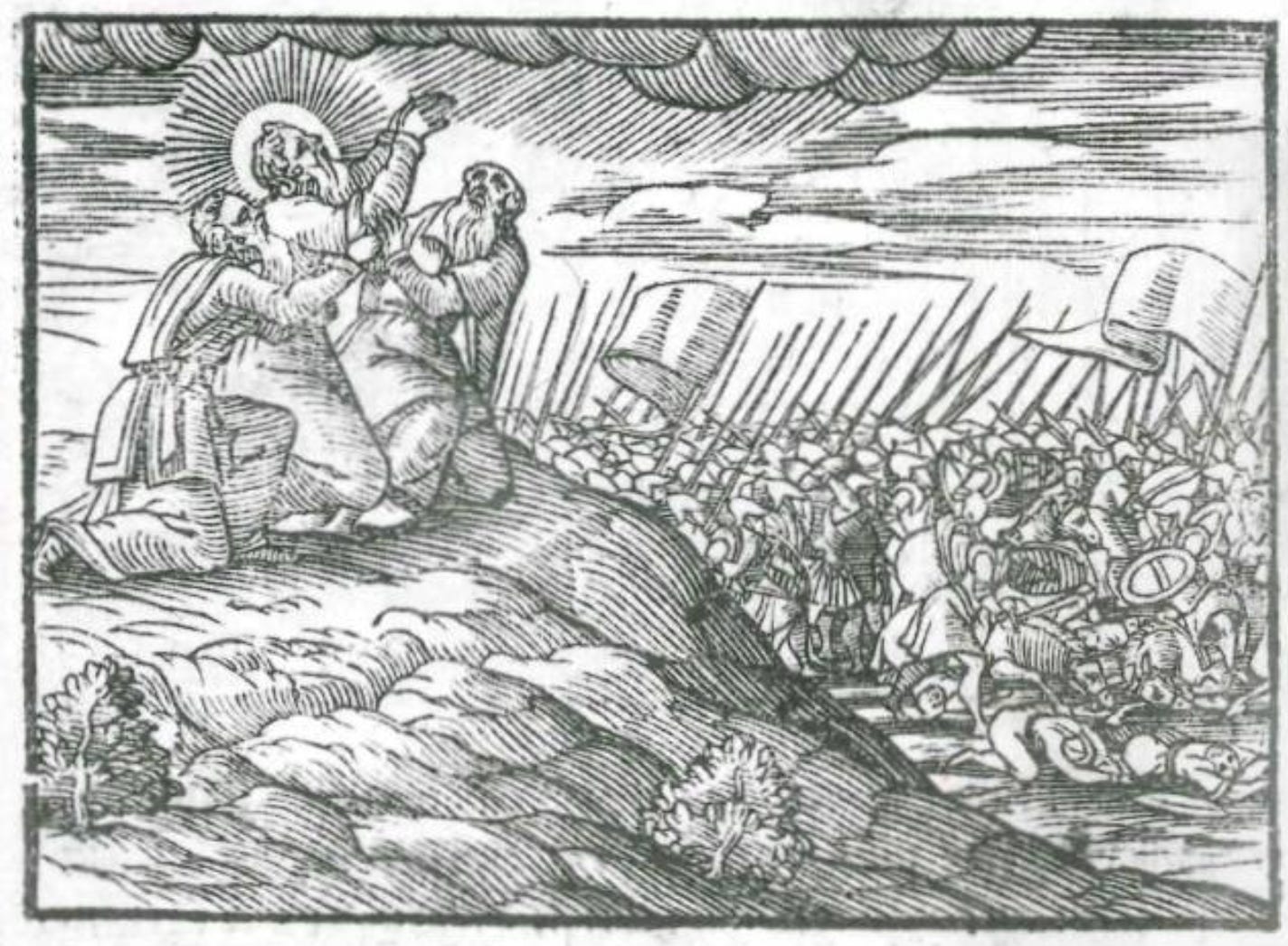

Joshua did as Moses told him and fought with Amalek, while Moses, Aaron, and Hur went up to the top of the hill. Then, whenever Moses held up his hand, Israel prevailed; but whenever he let down his hand, Amalek prevailed. But Moses’ hands grew heavy; so they took a stone and put it under him and he sat on it, while Aaron and Hur, one on each side, supported his hands; thus his hands remained steady until the sun set.” (Exod. 17: 8-12)

This is the dramatic biblical backstory of the battle with Amalek, and it was taken up as a model for prayer leadership in rabbinic literature. Pirkei D’rabbi Eliezer, an eighth-century midrashic work, describes how the Moses-like prayer leader should be supported in spiritual warfare by two assistants:

“Moses said to Joshua: Choose men for us, houses of the fathers, men who are mighty in strength and valor, and go forth and do battle with Amalek. Moses, Aaron, and Hur stood on a high place, in the camp of Israel, one on his right hand, and one on his left. Therefore we learn that the shaliach tzibbur is prohibited to officiate unless there are two are standing with him: one on his right and one on his left.”1

This model of the cantor and assistants as spiritual warriors, echoed in numerous other texts, would last for nearly a millennium.2 Medieval Ashkenazic pietists in Germany drew on these rabbinic texts as they developed their new ideas about the power of prayer. These mystics felt that the cantor was leading the people at a critical time and, like Moses, required assistants on either side in order to support Israel on its Day of Judgment.

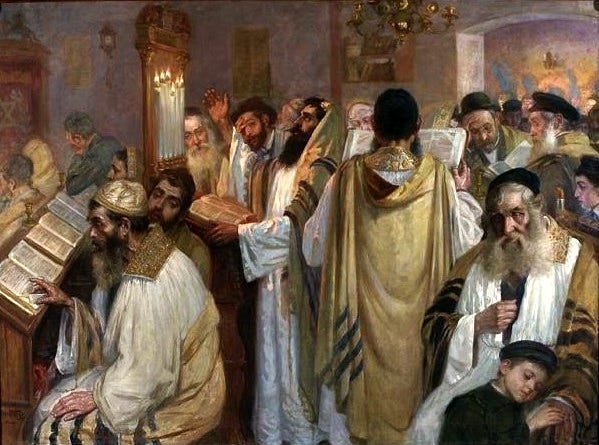

One of the most iconic medieval illustrations of this comes from the Leipzig Mahzor (c. 1310), pictured above. The image shows the cantor as he begins the HaMelekh prayer of the High Holiday Shacharit service, flanked by two seganim (assistants). Rabbi Eleazar of Worms, for whose community the Mahzor was created, describes this practice in his Sefer HaRokeach: “About the men who stand next to the hazzan: According to the Mekhilta, ‘Aaron and Hur support [Moses] from either side.’ Therefore the Sages say that no fewer than three men should go forth to the shrine during the public fast.”3 A century later, the Hagahot Maimunot, compiled by Meir HaKohein of Rothenburg, adds: “This is our custom for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, and it is fitting to do so.” We see more about the stakes of this spiritual battle in a 14th-century manuscript:

“And in such way that they would stand next to Moses at the hour of battle, so too on Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur one must stand by the sheliach tzibbur, for the satan prepares himself to accuse on those days more than any other days of the year, because they are the Days of Judgment, and one must battle with him…”4

These mystical pietists, in many ways, created the cantorate as an honored, spiritually-charged vocation.5 This is because they believed so strongly in the importance of song and prayer, especially against the evil forces that surrounded them.6 Under their leadership, liturgical poetry and its cantorial champions flourished and the core melodies of Ashkenazic prayer chant took form.7 Even though these Jews were ever in the shadow of violence and hatred, they marshaled their moral force to conquer the satan, the forces of sin within, on their long heroic quest towards spiritual grandeur.

Jewish musicologists have long seen this medieval practice as the forerunner of the infamous early modern cantorial assistants, the meshorerim . This is not, however, substantiated by the sources. The pietist custom of High Holiday seganim continued unabated in Western Ashkenazic communities through the seventeenth century. But it was largely displaced thereafter due to the widespread influence of the Shulchan Aruch, which circumscribed this practice to Yom Kippur evening alone. Today the remnants of the seganim among Ashkenazic Jews can only be found in the ritual court of three formed as part of the Kol Nidre service.8

Yet cantors and meshorerim well remembered the image of Moses at the Battle of Amalek. Yoel Sirkis, Hazzan of Česka Leipa, recalled it in his defense of the meshorerim, firm in his belief that these assistants were essential for the musical and mystical support of the task of prayer.9

In this difficult time, our prayers matter. But our ability to be of support, to hold up the hands that defend and guide our people like Aharon & Hur, is of even more importance. The history of cantors in spiritual warfare reminds us that we need to show support and to lend help in the long, tiring task ahead. As a new battle against Amalek arises, let our hands not waver.

Pirkei D’Rabbi Eliezer 44:4

See also Pesikta d’Rav Kahana 3:1; Masechet Soferim 14:14, and Mechilta d’Rabbi Yishmael 17:12 for other examples.

Mechilta d’Rabbi Yishmael 17:12; See Sefer HaRokeach, Hilchot Rosh HaShanah, no. 203. Translation from Kogman-Appel, A Mahzor From Worms, 76. See note 5 below.

The Hamburg State and University Library Carl von Ossietzky, Cod. hebr. 17 Peirush Machzor Minhag Ashkenaz, c. 1318. Cited in Elbogen, Studien zur Geschichte des jüdischen Gottesdienstes. Berlin: Mayer & Müller, 1907, p39, note 3.

This was unique to the Ashkenazic pietists of the Rhine. In contrast, the famous French rabbi Rashi (1040-1105) wrote: “Cantor (hazzan)— he is the functionary (shammash) of the community and I never heard that he has any significance," See Rashi on BT Makkot 22b.

For an excellent profile of the medieval cantorate in relation to this mahzor, see Katrin Kogman Appel, A Mahzor from Worms: Art and Religion in a Medieval Jewish Community (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012): 60-93.

Eric Werner’s Ashkenazic musical history, A Voice Still Heard, lionized this era as a golden age of the cantorate before the profanations of early modern decadence: “All nostalgic memories of those ‘good old days’ of hazzanut are either pipe-dreams or documents of ignorance --and sometimes even combinations of both. The truly great and indeed historic epoch of the Ashkenazic hazan was that of the Missinai tunes, the period between 1200 and 1450 (Werner 13).”

Polish commentators on the Shulchan Aruch would further limit the practice to the Kol Nidre service alone. Joel Sirkis (Poland, 1561-1640) observed with surprise that the prevalent custom was that cantorial assistants (seganim) returned to their places after the call to worship (barchu), whereas the custom for them to stand near the cantor for all of Yom Kippur was practiced only in a few communities. See the Shulchan Aruch, Orach Chayyim S. 619 Bayit Chadash ad loc.; See also Magen Avraham ad loc.; Levush ad loc.; It is notable that this practice remain among Italian and Sephardic Jews, who employ assistants called “seganim” on the High Holy Days for the recitation of piyyutim.

On note 7, wondering if this type of music was based on “modes”, sort of a minor key? Were chords used or was it a singular melody? Noting the historical context of the times, could it have been anything other than minor?

I love how well researched this is!