High Holidays with James Brown

featuring prostration, exorcism, and the Avodah service in a bar

I’m a cantor, so generally I feel like I know what Jewish prayer means and feels, both in community and personally. But sometimes I get a good dose of Socratic knowledge —i.e. an awareness of how little I know after all.

Two Hebrew texts from centuries ago recently reminded me of this inconvenient truth. And the key to both of them came from an surprising source — the Godfather of Soul, Mr. James Brown.

Friends of mine recently introduced me to one of the epic musical performances of last century— James Brown’s appearance with the Famous Flames in the star-studded 1964 concert film, the T.A.M.I. Show. This legendary performance featured Brown’s ecstatic vocalism and electrifying dance moves, which even Keith Richards of The Rolling Stones was intimidated to follow on stage.

The moment which ignited my religious imagination was in “Please Please Please,” featured above. James Brown, in a fit of passion, suddenly drops to his knees, crooning to the microphone like he’s cradling his fainting lover. This dramatic descent is followed by members of the Flames helping a seemingly-depleted Brown up from the floor, putting his cape over him in a theatrical attempt to have him throw in the musical towel. Yet time after time, the weakened Brown resurrects himself, jolting back to the microphone to pour out his heart and soul.

This performance made me wonder —what is really going on here? James Brown was borrowing from the significations of gospel music and tent revivals, in which preachers would similarly “scream, yell, stomp their feet, and fall to their knees during sermons to provoke responses from the congregation.” His gospel quartet-turned-secular supergroup was powerfully bringing that ecstatic worship form to the concert stage — an inversion of the old religious trick of transforming magical, erotic, and/or ecstatic musical forms into sacred adorations with moral messages.

But what really stuck with me were the repeated falls and revivals of James Brown — three in total. I couldn’t help but associate them with the three times each year that I myself fall to the floor and have people help me up off the ground — as the cantor on the Jewish High Holidays.

So what can James Brown’s “Please Please Please” teach us about the Days of Awe? For that, we need a deeper look at Judaism’s own floor-hitting practice of prostration.

I. A Prostrate Examination

The practice of full prostration — extending one’s whole body face down on the ground in deference to a higher authority — was a standard practice in the biblical world. It was a normal response of deference to god(s), kings, and even guests. It was also regularly used throughout the service in the Jerusalem Temple.

The rabbis, however, made a deliberate choice to largely discontinue this practice. This is because they had developed a new theology and sense of status relative to God. Whereas prostration indicated a vast difference in power between two parties, the rabbis instead chose to bow to their Creator — a deferential gesture borrowed from the more interpersonal spheres of relations between parent and child and between master and student. This is to say that the rabbis intentionally set out a system in which they were, at the level of gesture, on more familiar terms with God than their biblical forebears.

The High Holidays, however, stand in contradistinction to this more intimate body language. As Uri Ehrlich points out in his study of the nonverbal language of Jewish prayer: “On fast days and the High Holidays, with their dominant spiritual atmosphere of insecurity, remoteness, and judgement, a time of “trouble in the world” (BT Shabbat 10a), the worshiper approaching God stresses the gap between them; thus we find increased use of prostration.” 1 So the rabbis allowed prostration to remain in the vocabulary of High Holiday Prayer — but only for its most intense moments.

This permission for prostration persevered, perhaps also because the rabbis could not abandon their memory of its power. A midrash tells us how biblical prostration had an almost magical quality to affect the world:

Bereishit Rabbah, 56:2

R. Yitzchak said: Everything happened as a reward for prostrating. Abraham returned in peace from Mount Moriah only as a reward for prostrating. “And we will prostrate, and we will come back to you.” Israel were redeemed only as a reward for prostrating: “And the people believed … then they bowed their heads and prostrated” (Ex. 4:31). The Torah was given only as a reward for prostrating: “And prostrate yourselves from afar” (Ex. 24:1). Hannah was remembered only as a reward for prostrating: “And they prostrated before the Lord” (I Sam. 1:19). The exiles will be reassembled only as a reward for prostrating: “And it shall come to pass in that day, that a great horn shall be blown; and they shall come that were lost … and that were dispersed … and they shall prostrate to God in the holy mountain at Jerusalem” (Is. 27:13). The Temple was built only as a reward for prostrating: “Exalt the Lord our God, and prostrate at God's holy mountain” (Ps. 99:9). The dead will come to life again only as a reward for prostrating: “O come, let us worship and bend the knee; let us kneel before the Lord our Maker (Ps 95:6).”

The rewards — or magical powers—of prostration are ample. Perhaps this is because a more hierarchical or transcendent theology inheres more dramatic gestures of obeisance, as certainly were on display in the Temple. It follows that the rabbis, who were trying to cultivate Jewish religion around a more immanent (or at least intimate) presence of God, banished this practice of the hierarchical past to the liminal fringes of their holiest days — specifically the Great Aleinu and the Avodah Service.

Watching the musical revivals of James Brown, I cannot now help but think that the prostrations of the High Holidays are actually supposed to be akin to resurrections.

After all, these are days, especially Yom Kippur, on which Jews rehearse their own deaths: wearing a white shroud, saying the confessional, proclaiming the Last Judgment, engaging in mourning practices (including fasting), and prostration. This last practice involves being as close to the ground as possible, an imitation of the grave itself. With this rehearsal of death, it’s no wonder that the prayer leader, like James Brown, needs help getting up.

That the High Holiday prostrations should somehow take on the symbolic import of a resurrection of the dead (or the ecstatic drama of a revival tent) is an idea that would be totally lost in most synagogues today. Outside of intentional communities who double down on these complex and powerful liturgies, these moments are ironically often ones of the lowest energy. It is perhaps no small irony that the moments of rehearsing resurrection are, in many synagogues, the most “dead.”

Yet when we look deeper into the two prayers which feature full prostration — Aleinu and the Avodah Service — we find liturgical moments infused with surprising musical and magical powers.

II. Aleinu and Exorcism

The Aleinu prayer, recited at the end of nearly every Jewish service, originated in the rabbinic era as a prayer for Rosh HaShanah. Its daily recitation affirms that one accepts ol malchut shamayim — the yoke of God’s kingship — which is in particular focus on the Jewish New Year. The retaining of prostration for this prayer is fitting, as its liturgy stands as the quintessential expression of God’s transcendent kingship over all of humanity. It is no surprise that the melody of this central prayer, at least among Ashkenazi Jews, is among the longest remembered tunes known as misinai melodies whose antiquity goes back to the cradle of medieval Ashkenaz (or further!).

Yet there is some deep magic in this liturgy—perhaps the same magic that inspired the sacred melody, or caused the text to spread from Rosh HaShanah into every single daily service. The prayer’s proclamation of God’s kingship — inside and outside the synagogue gives spiritual succor to those experiencing life’s difficulties; its affirmation of faith and ultimate judgment strengthens those trying to walk a path of righteousness.

But Aleinu is also apparently good at driving out demons.

If you know the name of Rabbi Yosef Karo, you probably know him in connection to his massive influence on Judaism through his legal code, the Shulchan Aruch, which came to define normative practice for Jews across the world. What you probably don’t know is that he was also responsible for the first known exorcism in early modern Jewish sources.

What follows is a bizarre story of rabbis, reincarnation, and evil spirits. And it features Aleinu in a starring role as the rabbinic exorcist’s incantation of choice:

I further testify that in that year, the year 5305 from the creation (1545 C.E.), here in the upper Galilee, a spirit entered a small boy, who, while fallen, would say grand things. Finally, they sent for and assembled many great sages, along with men of deeds—myself among them. The sage R. Joseph Karo, may peace be upon him, came and spoke with that very spirit. [The spirit] did not respond to him until he decreed the punishment of niddui (excommunication) upon him unless he spoke. He then spoke and responded. The sage said to him, “What is your name?” He said, “I do not know my name.” “Who are you?” “I am a dog.” “And before that what were you?” “A Black Gentile.” “And before that what were you?” “An Edomite [Christian] Gentile.” “And before that what were you?” “From those people who know the Holy Tongue.” He said to him, “What were your first deeds?” He said, “I do not remember.” “Did you know Torah or Talmud?” “I used to read the Torah but I knew no Talmud.” “Did you pray?” “I did not pray except on the Sabbath and festivals.” “Did you don phylacteries?” “Never did I don phylacteries.” He said to him, “There is no fixing you."He said, “They already decreed on me …”—that he cannot be fixed.

He said that it had been two years since he departed from the body of the dog, and that since the father of the boy killed the dog, he said to the boy’s father, “Just as you distressed me when you killed the dog that I was within, so I will kill your one and only son.” At that moment the sage R. Joseph Karo recited over him, “Aleinu LeShabeach--It is incumbent upon us to praise …” seven times, forward and backward, and he decreed upon him a niddui to depart from anywhere in the Galilee. And so it was that the young man was healed. This is what I saw with my own eyes at that Holy Convocation.”2

This may seem a wild scene for the contemporary Jew. And yet the power of Aleinu is there as the religious counterspell to claim God’s authority against an evil spirit, driving it out and saving the life of a young boy. This esoteric power of Aleinu is lost in its prosaic proclamation in daily worship, or in the stuck formality with which this otherwise shamanic moment is presented on the High Holidays. The ancient melody, combined with the practice of prostration, both re-emphasize the magical core of this prayer — a symbolic exorcism of false authorities (demonic and otherwise), and uniting the world under the kingship of God.3

I’m not saying that prayer is always so spellbinding. But perhaps we might feel the weight of these magical stakes when we say this daily prayer — or minimally when we drop to the floor on Rosh HaShanah.

III. The Avodah Service—in a Bar

There is perhaps no more intense, performative ritual moment on the High Holidays than the Avodah service, the liturgical epicenter of Yom Kippur. Its liturgy tells the complex story of the ritual of the High Priest as he confessed the sins of the people, purged the sanctum of impurity, and led all of Israel to joyful forgiveness before their God. The traditional Ashkenazic poem, Amitz Koach, describes this ritual as the telos of all creation, recounting the history of the universe from the world’s beginning to the intricate steps of the high-stakes priestly drama. As part of this liturgy, the shaliach tzibbur/cantor makes three prostrations, mirroring those of the High Priest in his process of personal and communal atonement.

This drama more often than not falls flat. The long, esoteric poetry in literary Hebrew with its detailed accounts of sacrificial activities (including the counting of blood spatters) aren’t exactly low-hanging liturgical fruit. My years of Avodah services have been abridged or hybridized with more modern features—English poems, sermonettes, meditation, and responsive singing with the reenacted priestly confessions and prostrations, accompanied by the medieval misinai melody, V’Hakohanim.

I polled my fellow prayer leaders in advance of this post to ask for their favorite experiences of the Avodah service. Some leaders had created responsive musical forms to keep the congregation chanting with them through the long poetic narrative. Other leaders pointed me to cantorial recordings which showed a liturgy uplifted through complex cantor-choir interplay. The “traditional-egalitarian” style utilized a combination of simple chant and expressive reading throughout, building drama until the joyful, proclamation of Mar’eh Kohein — the liturgy extolling the joy of the people when the priest successfully returned from the Holy of Holies.4 These prayer leaders reminded me of how much potential already lay within the traditional liturgy.

But whatever I thought I knew about the Avodah Service was recently shattered by a text I discovered in one of my PhD dissertation’s core sources — Sefer Teudat Shlomo (1718) by Rabbi Shlomo Lifschitz. This text is one of singing the sublime moments of the Avodah service — not in synagogue, but in a tavern:

At festive meals, there are those who rely on what the sages of blessed memory said: “Let the master sing for us [a mournful song]...woe unto us for we shall die.”5 Even so, one should not do this!

Several times I have heard it said: “Let the master sing for us something spiritually provoking [איזה התעוררות], that is melodies from the Days of Awe. ָָAnd the cantor would sing “Halleluyah, [praise] God in his sanctuary!” And he strikes his fellow, and gives the cantor a coin.6 Then [the man] eats, drinks, and gets up to disport himself, and does not listen at all to what the cantor is singing. It is like the cantor sounding [the shofar] into an empty pit without water – only wine!7

And sometimes the cantor sings the avodah service while [the guests] serve their mouth with eating and drinking – wherefore is this spiritual provocation? Therefore it is better to make other melodies and not ones that are done on the Days of Awe, for of these it is said: “Your children have made us like a harp which is played in taverns.”8

What a scene. Instead of the liturgical holy of holies, Ashkenazi Jews are asking their cantors to sing the Avodah service in a tavern — a liturgical minstrelsy performed by cantors with all of the sacral aura of a jukebox.

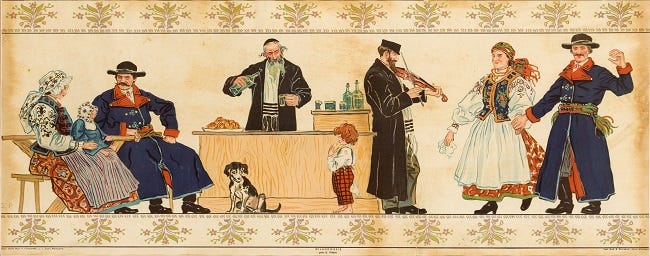

There is a lot to unpack here. Firstly, we should not be surprised to see festive meals in a tavern setting. Ashkenazi Jews in Western Europe were largely of a lower socioeconomic class, and were furthermore banned from owning property in many European cities and protectorates. A great many sacred events — especially festive meals [seudot]— occurred in the “third space” of the local pub.9

Even more fascinating in this source is the concept of a “melody of spiritual provocation” [niggun hit’orerut]. This is the sort of melody, typical of the High Holidays, that is supposed to inspire one to repent and changing one’s ways. This is contrasted by the author earlier on with the niggun simcha — the melody of joy. I have not found this fascinating dichotomy presented in any other source. I asked my learned colleague, Rabbi Ebn Leader, who found an example of a similar contrast post-R. Nahman of Breslav. It does not concern music, but rather with types of teaching — teachings of provocation [sichot hit’orerut] and those of strengthening [sichot hizzuq]. The latter “make you feel better about yourself, and the former being wake-up calls so [that] you know what you have to improve.”10

Whatever its origin, this gives amazing texture to the power of the actual Avodah service melody, such as it was in the early eighteenth century, as one that was known to be among those that inspired one to reflect and repent. R. Lifschitz’s scene of the profanation of the Avodah service for entertainment also reveals the emergent role of cantor as a public singer — bringing forth moving, yet incredibly sacred tunes as background music to a public feast.

Or in another way of putting it: “Play it again, Sha”tz.”

The power of these liminal, prostration-filled liturgical moments of the High Holidays isn’t just academic. It points to the ancient power of these rituals to drive out evil spirits, to move people to repentance, and to signify our personal resurrection in moments of spiritual significance.

I’m grateful to James Brown for the reminder. I don’t expect to be as electrified as he is while I am fasting next Yom Kippur. But I am hoping for a revival.

Uri Ehrlich, The Nonverbal Language of Prayer, 46.

Translation by J.H. Chajes in Between Worlds: Dybbuks, Exorcists, & Early Modern Judaism, 141-2.

Cf. Malachi 2:12: Have we not all one Father? Did not one God create us? Why do we break faith with one another, profaning the covenant of our ancestors.

This joyful melody by Yigal Calek has come to prominence in such communities over the last several decades:

BT Berachot 31a. This scene describes the wedding feast of Mar ben Ravina, in which Rabbi Hamnuna Zuti sings a mournful song on account that the feast had become too excessive.

Cf. Mishnah Bava Kammah 8:6.

Cf. M. Rosh HaShanah 3:7; Gen 37:24.

R. Shlomo Lifschitz, Sefer Teudat Shlomo, 22a.

The outsized implications of tavern culture on the history of Ashkenazic music is one of the biggest unintentional discoveries of my PhD research. I am planning a full length academic article on this down the line.

R. Ebn Leader, personal communication.