Today, I want to tell you about Jewish Early Music.

I’ll admit, it’s probably a subject haven’t heard of before. You won’t find it while you’re doomscrolling or worrying about the dinner conversation this Thanksgiving.

But it is a fertile musical field, bursting with new growth from a rising generation of scholars and performers. Today, I’d like to take you on a hike through that field, and then to introduce three living heroines who have long been tending its musical ground.

The term early music describes the pre-modern periods of the Western classical tradition, including the Medieval (500-1400), Renaissance (1400-1600), and Baroque (1600-1750).1 Unlike the loud, emotional, and nationalism-infused masterworks of the nineteenth century, these earlier repertoires ephemerally transport our modern hearts and bodies back to pre-modern sensibilities.

I began to fall down this Wonderland-like rabbit hole when I discovered that my own research on cantors was largely concentrated in the heyday of the Renaissance and Baroque eras. Some of history’s most exciting cantorial innovations happened during Bach’s life (1685-1750), for crying out loud!

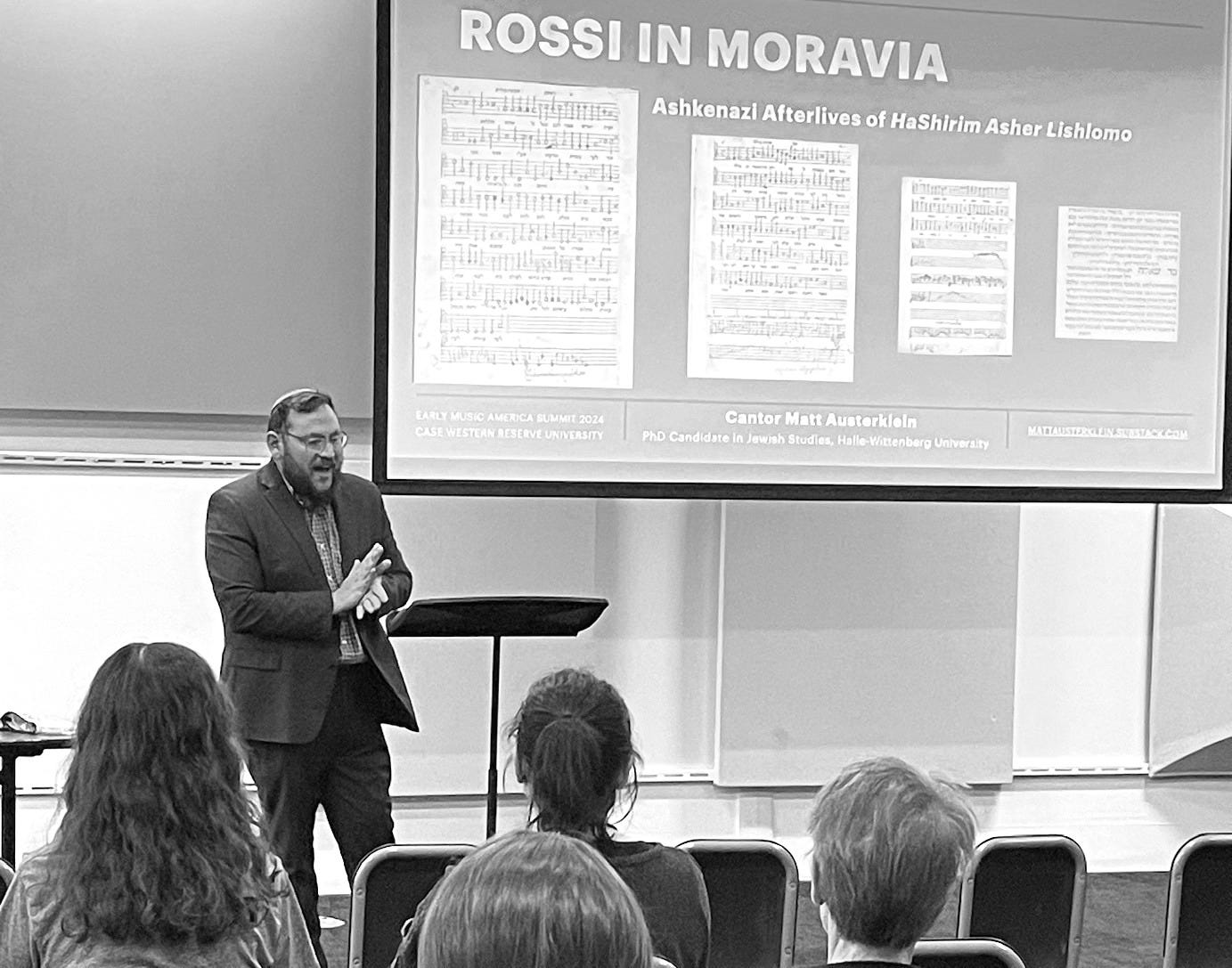

But I had no idea what I was missing until I attended the Early Music America Summit at Case Western University in Cleveland last month. The summit is an annual gathering of Early Music ensembles to share research, techniques, repertoire, and love for ye olde music. I love immersive environments where I am a novice and really have to stretch my mind. And stretch I did, whether it was studying the rules of ficta, the repertoire of late-medieval theatrical nuns, or the regional variants of Irish fiddle playing. This was music with guts (and I mean real gut strings), offering a visceral encounter with our musical past in order to re-envision a different social and musical present.

Thank you for reading Beyond the Music! If you enjoy reading this newsletter, please consider supporting me with a paid subscription.

The question for me was — where were all the Jews? Our small yet mighty people has been a constructive part of countless world cultures, yet our story has often been musically told by others, whether as characters in the New Testament or Qur’an or as footnotes in music history books. The main difficulty is that Jewish music cultures are largely oral and unnotated; historical Jewish musicology thus requires summoning the musical aether of the past through many sources: sound studies, poetic analyses, thick descriptions, and constructing meticulous musical genealogies between current and ancient oral traditions.2

Our own era is blessed with wonderful scholar-performers reanimating this world of Jewish Early Music. In North America, these include Elizabeth Weinfield’s revival of the compositions of the converso and viol player, Leonora Duarte (1610-1678); Rebecca Cypess’ work on the eighteenth-century Jewish salonniere and Bach collector, Sara Levy; and recent performances from the Newberry Consort, Raritan players, UCLA Early Music Ensemble, as well as vocalists Anne Slovin and Ian Pomerantz.

But for today, let me take you to Europe, where it is my pleasure to introduce three female artists who have been in the vanguard of Jewish Early Music for over twenty-five years. Their bright stories are lights forged amidst the shadows of European Jewish life, with many lessons to offer us on the other side of the Atlantic.

I. A German Pioneer: Jalda Rebling

Jalda Rebling grew up in a musical household in the shadow of the Holocaust. Her mother, Lin Jaldati, was a famous Yiddish singer and dancer from Amsterdam whose immutable musical lifeblood survived three concentration camps. Jalda herself graduated from the famous Ernst Busch University for Theatre Arts in Berlin, and worked in German theatre, TV, movies, and radio while raising three children. But her career pivoted when her mother brought their family together around a musical program to honor Anne Frank. Lin and her sister Janny had been the last people to see Anne & Margot Frank alive while in Bergen-Belsen, and the Rebling family carried their story forward with a memorable musical tribute, performing to acclaim across the continent.

While working as a Yiddish music performer in East Germany in the late 1980s, Jalda found herself at a Kristallnacht commemoration with a curious thought: Why are they playing klezmer at this event? Surely there must be early German-Jewish music! This sent her to the state library, where she discovered the works of A.Z. Idelsohn, Baroque-era Yiddish songs, and the story of the minnesinger Süsskind von Trimberg, arguably the first documented Jewish poet in the German language. These revelations, supported by her fellow musicians Hans-Werner Apel, Stefan Maas, Susanne Ansorg - Fidel (many alumni of the Schola Cantorum Basilensis), led to two Jewish early music recordings: Juden in Deutschland (1994) and Jews in the Middle Ages —from Sepharad and Ashkenaz (1999).

Jalda and her ensemble used combinations of old manuscripts, Hebrew cantillation, and early music contrafacts to realize their musical experiments. Their audiences were confounded: Where’s the klezmer? Jalda reassured them: “Jewish culture in Germany is German culture since Charlemagne.” She played exhibitions, conferences, and concerts all over Germany, featuring, among many themes, the music of Ovadia HaGer (writer of the earliest notated Hebrew music), the complete poems of Süskind von Trimberg, and musical stories of Jewish women in medieval Germany.

Along the way, she got re-introduced to the world of synagogue music, and became a cantor through ALEPH: Alliance for Jewish Renewal and the patient and generous mentorship of Cantor Jack Kessler z’’l.

Today, Jalda is continuing to build musical bridges in Germany, particularly with Muslims and Christians, including new projects exploring the intersection of Jewish music and maqam in Muslim Spain.3 To this day, she remains fascinated by the medieval Jewish world:

“It is a universe with so many treasures to find. It needs a lot of creativity to dig it up. Collaboration with our Christian and Muslim siblings is for me the art of possibility to live together playing great music.”

II. Yiddish on the Rialto with Avery Gosfield

A lifelong early music performer, Philadelphia-born Avery Gosfield found herself strangely exposed to the poetic world of Jewish early music from a late night Italian television show. Watching a redeye performance of a sixteenth-century Judeo-Italian Purim play on the biweekly Jewish culture program, Sorgente di Vita, her ensemble’s former co-director, Francis Biggi, had an epiphany that the play was written in ottava rima — an Italian poetic form that is almost always sung, dates from the Middle Ages, and is still performed today.

This led Avery on a hunt for more poetry by Jewish authors that used forms that we know were sung, at least upon occasion. This included works by Elye Bokher’s Bovo Bukh, R. Mordechai Dato’s Purim play, Leon Modena’s Hebrew translation of the Orlando Furioso, and many, many more, to perform with her early music ensemble, Lucidarium. With the addition of vocalist and Judeo-Italian music master, Enrico Fink, the group launched into new interpretations of the soundscape of the Jews of early modern Europe. These included “La Istoria de Purim” on the Jews of Renaissance Italy; “Ayn neue Lid,” exploring Yiddish repertoire, and many multidisciplinary concert projects.

Upheavals in European and American politics led to more serious musical ventures. “Iter Hierosolymitanum – Jew and Christian at the Time of the Crusades” looked at medieval injustices from the perspective of the victims, trying to accurately show anti-Judaic rhetoric and other disturbing texts, paired with Jewish Crusade song repertoire lamenting the massacres and the results of hatred. This movement back towards the Middle Ages also yielded “Ritual Echoes”, a music and video project filmed in the miraculously preserved medieval mikvah in Speyer, and whose beauty is given poignancy by the pitiful timelessness of the texts in our post-October-7th era.

Recent projects also include “The Babel project,” exploring the parallels between the various forms of historical and modern Jewish music; Moriscos y Marranos, which underlines the links between the Jewish and Muslim expulsions from Spain and Portugal; and “Silent Shadows,” a documentary that discusses the history of antisemitism and the impact of micro and macroaggressions from the end of the 11th century to the present.

Avery describes her life in Jewish Early music as meaningful opportunity to share between worlds:

“One of the nicest things about working in Early Jewish Music is the opportunity to bounce back and forth between Jewish and Early music festivals. At Jewish festivals, we have the opportunity to show that Jewish music is not limited to klezmer, teach little-known aspects of Jewish history and culture, and demonstrate the important cultural exchange between Jews and their neighbors throughout the diaspora. In Early Music festivals, it can be a first encounter with Jewish culture, serve as living proof of our role (and presence) in Europe from the time of the Roman Empire, and awaken curiosity. And people can have a nice time listening to good music too.”

Avery’s method of using historical European poetic forms and melodies as the basis for performing “early Jewish music” is ultimately a practical one. With few exceptions, none of the Jewish poems that Ensemble Lucidarium performs survived with music. She describes her process of re-envisioning melodies for medieval and Renaissance Jewish texts as a form of “educated forgery:”

"In setting the Jewish poetry to music, I use a pragmatic approach. First, I study the poetic form in depth, and learn it by heart. Then I look through sources for notated pieces that set the same meter and are temporally and geographically appropriate. Next to historical sources, I look for recordings of orally transmitted Jewish music, once more (when we know anything) from an appropriate area.

Sometimes the process is easy, sometimes it’s literally looking for a green grain of sand at the beach. More than authenticity, I have to feel that the melody fits the mood and syntax of the poem, according to my 20th-21st century aesthetics (and 45-year experience playing early music). It’s what the Globe Theatre calls a “best guess” interpretation, and I call an “educated forgery.”

It’s not an easy process, as it involves researching the historical context of the poetry, and according to the context, defining what the appropriate sources may be. Finding the right music usually involves combing through dozens of melodies before finding the right one."

For Avery, the quest for authenticity in early Jewish music is ultimately one of centering the voices and narratives of Jewish poetry, serving the text and interpretation more than the false god of historical melody. Amplifying those voices, often with a moral or political message, is at the unapologetic heart of her work. “I get flack for going backwards,” she quips. “but the music is far from secondary, it's essential — not only to get our message across but also because the aim of this crazy research is also to create a thing of beauty.”

III. The Joy of the Soul: Diana Matut

Diana Matut is one of the best kept secrets in Jewish music today. Mostly working in Germany, Diana has excavated the depths of early Yiddish song in unprecedented ways, both as an academic and performer.

Growing up behind the iron curtain, Diana developed a familial love of classical music through the works of Jewish musicians like David Oistrakh, Yehudi Menuhin, and Joseph Schmidt. After German unification, she became inspired as a young woman by the twin Yiddish-singing muses of Chava Alberstein and Jalda Rebling. Jalda’s pioneering Jewish early music work in particular enabled Diana to envision a life combining her own two loves of Early music and Yiddish song. Then during her first year studying at Oxford University, Helen (Khayele) Beer pointed out to her the “Wallich” manuscipt in the Bodleian Library. This fascinating manuscript contained dozens of early Yiddish song texts and their German contrafacts, and would eventually became the focal point of Diana’s doctoral dissertation and first monograph.

Diana has since established herself as a global authority on early Yiddish song. She is fluent in both Eastern Yiddish and Old/Western Yiddish, teaches for worldwide Ashkenazic cultural events and institutions, and recently wrote a multilingual libretto for a new oratorio about Glikl of Hameln. But one of my favorite parts of her work is her band, Simkhat Hanefesh (“Joy of the Soul”), which interprets early modern Yiddish song using Baroque improvisational techniques.

Based on the name (and featuring the content) of a 1727 book of notated Yiddish morality songs, Simkhat Hanefesh breathes new life into the early spirit of Ashkenazic Jewry in Europe. Klezmer fans may be surprised at its “Western” sound, much like Jalda Rebling’s German audiences. But musical excavations of Simkhat Hanefesh reveal how the music of Renaissance and Baroque Europe passed easily through the air, creating shared repertoires of melody between Christians and Jews.

The group’s first album is from a decade ago, and I’m happy to here share a teaser track, “Pessachlied (Passover Song)” from their upcoming album, Eine Reise durch Aschkenaz: Die Fahrten des Abraham Levie 1719-1723 (A Journey through Ashkenaz: The Travels of Abraham Levy, 1719-1723), musically walking listeners through the soundscape of this notable historical Jewish traveler.

My appreciation for Diana also cannot be separated from the personal realm. It was she who ultimately found me, a congregational cantor with a little known masters thesis, and invited me to apply for a faculty-level fellowship at the Oxford Centre for Hebrew & Jewish Studies in 2019. I do not know how she convinced the Oxford dons to accept me when I had no doctoral credential. But by what only feels like providence today, I applied, was accepted, and spent two mind-expanding months with fellow scholars and friends. This launched me on my path today towards my doctorate, where Diana continues to assist me as my advisor, together with my old cantorial school professor, Edwin Seroussi. In helping open this altogether unexpected and deeply meaningful path in the course of my life, I owe her an eternal debt of gratitude.

These three matriarchs of Jewish Early Music have experimented, recorded, and performed for decades all over Europe, where the stakes of Jewish sound are as fraught as Europe’s own history with its Jews. Yet they are continuing to reforge sonic pictures of the Jewish past, with an eye to changing narratives and fostering inclusion and peace.

There is much work yet to be done in reclaiming the possibilities of Early Jewish music. May we continue to be inspired by all of those who have paved the way.

For the musicologists playing along at home, I know that people make careers arguing about years and nomenclature. Stay with me.

Edwin Seroussi and Naomi Cohn-Zentner have been especially masterful at drawing these songlines between past and present.

Thank you so much for introducing me to Diana Matut! She’s fabulous. I’m very familiar with Jalda Rebling’s pioneering work, but Matut is an absolute breath of fresh air. I’m glad to hear there’s a new recording coming out — their other material looked so old I was worried the group no longer existed. Maybe there’s hope for getting them to our Munich synagogue. 😎

This is fab. Sharing!!