Last week was a terrible nadir for world news and for the Jewish people, and there is a long road ahead. The entire state of Israel spent the week going to war, yo-yo-ing in and out of bomb shelters, attending funerals, and sitting shiva. Life for Jews in the diaspora is filled with a historical all-too-familiar rhythm of crying, disbelief, fear, prayer, tzedakah, and political action. Whither music at such a time?

To address this troubling question, I’m taking a note from Israeli writer

at . This past week, Shmuel wrote about an antidote to terrorism’s objective of have us eternally engaged outward in fear:“They want to stop us from living, caring, connecting, being….There’s no more important time to take good care of our physical and emotional health: not only to make living possible, but because that’s where all good choices begin.”

Music is such a center of healing, vitality, and connectedness. And we need that centeredness, even our hearts break and our hands rise to act. So despite the cloud of disorientation and grief which follows my belletristic wanderings, it is my prayer that what little I am able to write about Jewish music contributes to our caring, connecting, and being at this difficult time.

And now, the news:

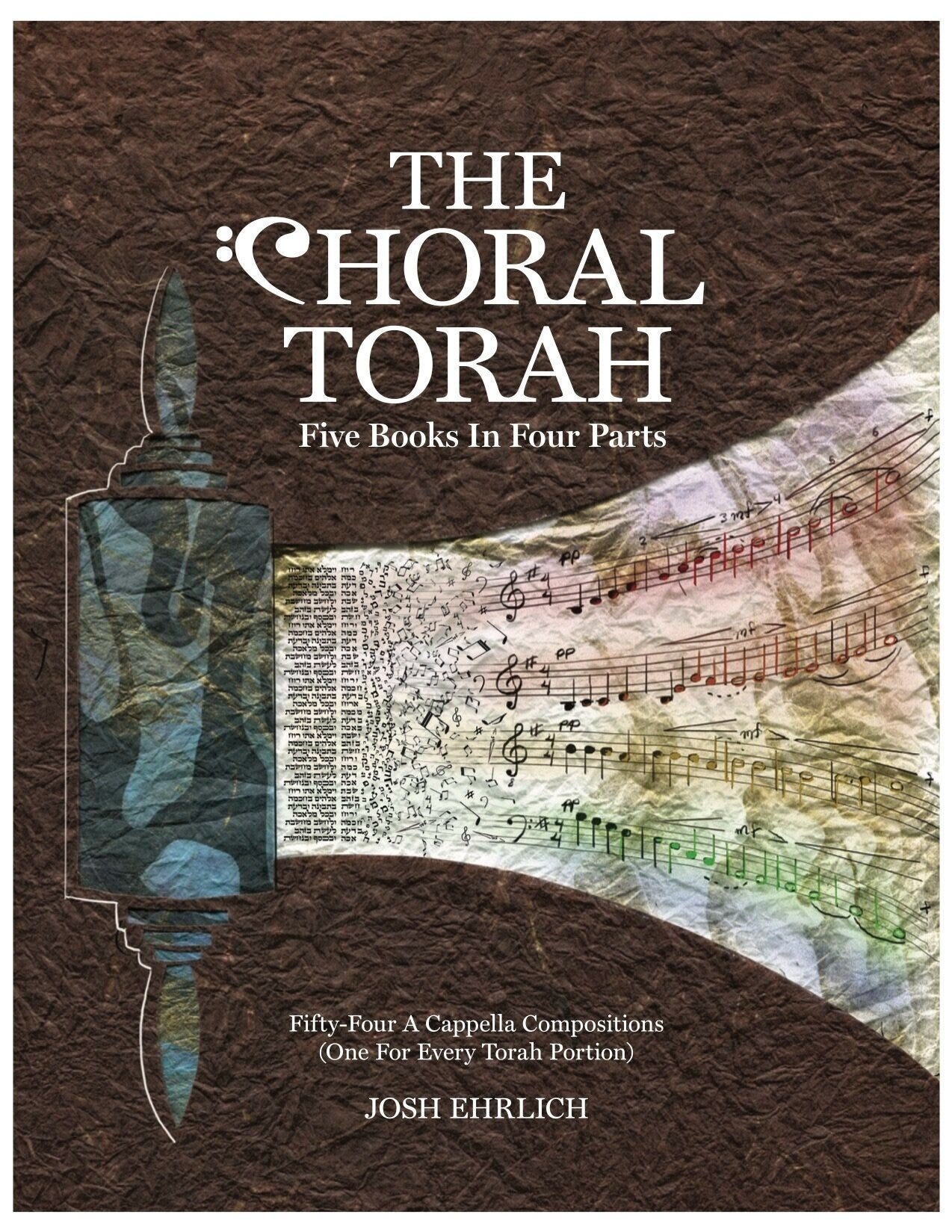

Today is Rosh Chodesh (the new month of) Marcheshvan, a joyous time and often celebrated by rabbis and cantors as the intense period of fall holidays comes to a close (though I don’t think pulpit clergy of any sort are getting a break with the recent news cycle). To offer praise and return to the affirming spirit of music, what follows is a short essay celebrating the joy of the Jewish choir (which we began studying earlier thhis monthhr this month), as well as exploring the complexities it faces in our own social and theological milieu. I originally wrote it as a foreword to The Choral Torah: Five Books in Four Parts, a brilliant book of contemporary choral pieces for each parashah of the year, composed by Cantor Josh Ehrlich.

Foreword: The Torah of the Choir

What is “Choral Torah?” In Judaism, the word “Torah” refers principally to the Five Books of Moses, read each year in their entirety by Jewish communities worldwide. But the term “Torah” may also refer to countless other sources of Jewish religious text, comprising early rabbinic literature (referred to as the “Oral Torah”), medieval commentaries, Jewish legal codes, and beyond. In modern times, the word Torah may refer to a more personalized and individual source of wisdom — one’s own teaching, based on the study of Jewish text refracted through one’s lived experience. This sense of personal Torah has been renewed from biblical roots: “My son, heed the instruction (mussar) of your father, and do not forsake the teaching (torah) of your mother (Proverbs 1:8).” The “Choral Torah,” beyond being the title of the book that lays before you, is also an invitation to ask: What is the teaching — the Torah — of the choral art form? What wisdom does it offer to humankind, and to Jews seeking religious and/or spiritual expression?

The earliest known choirs in the Jewish religion were found in the Jerusalem Temple, composed of levitical guilds who spent their lives in divine service. Without delving into the many biblical, rabbinic, and second temple period texts describing the Temple’s music, one can recognize that a fundamental aspect of all choirs is their complexity — large, coordinated musical forces requiring specialized training for the glory of God and the beautification of God’s worship. Reflecting on the advanced techniques and musical practices of the Temple, the poet Yehuda HaLevi (1075-1141) wrote the following in his Sefer Ha-Kuzari (chapter 2, verse 64):

אֲבָל חָכְמַת הַמּוּסִיקָה, חָשׁוּב בְּאֻמָּה שֶׁהִיא מְכַבֶּדֶת הַנִּגּוּנִים וּמַעֲמֶדֶת אוֹתָם עַל הַגְּדוֹלִים שֶׁבָּעָם, וְהֵם בְּנֵי לֵוִי, מִתְעַסְּקִים בַּנִּגּוּנִים בַּבַּיִת הַנִּכְבָּד בָּעִתִּים הַנִּכְבָּדִים, וְלֹא הֻצְרְכוּ לְהִתְעַסֵּק בְּצָרְכֵי הַפַּרְנָסָה בְּמַה שֶׁהָיוּ לוֹקְחִים מֵהַמַּעַשְׂרוֹת וְלֹא הָיָה לָהֶם עֵסֶק זוּלָתִי הַמּוּסִיקָה. וְהַמְּלָאכָה נִכְבֶּדֶת אֵצֶל בְּנֵי אָדָם, כַּאֲשֶׁר הִיא בְעַצְמָהּ אֵינָהּ גְּרוּעָה וְלֹא פְחוּתָה, וְהָעָם מֵחֲשִׁיבוּת הַשֹּׁרֶשׁ וְזַכּוּת הַטֶּבַע כַּאֲשֶׁר הֵם, וּמֵרָאשֵׁיהֶם בַּמְּלָאכָה

“Music was the pride of a nation which distributed their songs in such a way that they fell to the lot of the aristocracy of the people, that is the Levites, who made practical use of them in the holy Temple and in the holy season. For their maintenance they were satisfied with the tithes, as they had no occupation but music. As an art it is highly esteemed among mankind, as long as it is not abused and degraded, and as long as the people preserves its original nobleness and purity.”1

Thus woth musical specialization (such as that of the Levites) also comes other features: hierarchy and differentiation. In order for a greater music to be realized, musical roles (whether instrumental or vocal) must be differentiated. Individuals are called to embody musical possibilities beyond that which can be realized in an impromptu manner, and which require significant commitments of time and practice in order to preserve their “nobleness and purity.”

But what to make of this specialization and hierarchy when one of the primary, prophetic messages of the Bible is the equality of all human beings? How is God’s equal love of each human life to be modeled if some voices are heard above others?

This tension of values between equal human worth and the necessity of differentiation takes on an additional element in the musical sphere — the question of harmony. Western ideas of musical harmony, as theorized by the Greeks and passed through the ages, via Arabic and later through the aesthetic cultures of European Christianity, were part of a world outlook that emphasized cosmic order. All of the world was in divine balance; one need only harmonize one's mind and actions with this great truth. But for Jews, this philosophy was not an uncomplicated proposition. While “natural design” and cosmic order are found in one strand of Jewish thought, in many ways the Hebrew Bible is a subversion of this idea. The Israelites equally saw the world as profoundly broken and in need of repair — filled with slavery, poverty and injustice.

This contrast of worldviews within Jewish tradition may be acutely appreciated in the midrash of the bira doleket. This is a rabbinic story about how Abraham, the patriarch, discovers God. In one version of the story, Abraham's encounter with God comes from reflecting on the world and discovering order: “If a person was traveling in the desert and found a building aglow, would it be possible to say that this building did not have a master? So too, it is impossible that this world and skies have no leader and no creator.”2 In an earlier version of the midrash, Abraham is compared to one who comes across a building on fire. He looks at the world and says to himself: “one would conclude that this world has no supervisor!”3 In this version of the story, God comes down and says to Abraham: “I am the owner of the entire world.” The poignant part of these two stories is that the same two Hebrew words, “bira doleket,” could be translated in either manner — either as a “glowing building” or a “burning house.” Thus we discover the truth that people can look at the same world and see it very differently — as beautifully aglow or horrifyingly ablaze.4

The experience of harmony, sonically or otherwise, can come as a profound therapeutic experience — the music of a world beautifully aglow. It allows the listener and the musician to experience a unity beyond their ability to realize themselves, as a function of the specialized gifts of the musician. But like all hierarchies, it can mask the complexities and inequities that lie within — the experience of the burning building. How might we resolve this philosophical tension between order and disorder, between harmony and reality, particularly in our volatile age of smashing cultural norms, rising social movements, and the just desire to make sure that all voices are heard?

Perhaps this tension cannot be resolved, but rather calls us into a faithful hybridity, both in the practice of music and beyond. The choral experience, as the forty-two million Americans who sing in choirs can attest, has many powerful goods: inspiring wonder, cultivating close relationships, creating moments of immense beauty, and encouraging aspiration in the craft of musical expression which uplifts the entire ensemble. While choral music creates the classic “performer-listener” dynamic which is much derided, it does this, at its best, as part of an intentional relationship between those who make music and those who are assembled to hear it. Harmony cannot always encapsulate the truth of the world's brokenness, but it can provide stability, inclusivity, and love in a world of mistrust and identity politics.

The choral experience holds religious meaning in yet other ways. As Yehudah HaLevi observed, the levites of the biblical Temple were constantly occupied with music. In this way, they were brought closer to two profound goods — the practice of music and the spiritual life, being simultaneously devoted to both. It is here where the promise of Choral Torah is perhaps deepest — taking that which is most beautiful, and pointing toward that which is most good.

Josh Ehrlich's Choral Torah, the first of its kind (at least on American soil), fantastically reveals this truth. His work, exploring Torah verses through song, demonstrates what Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote: “A word has a soul, and we must learn how to attain insight into its life.”5 Those for whom choral singing and composition is a passion will discover that this spiritual insight can be attained through the choral medium. This book is a well of deep repertoire for choirs of all stripes — liturgical or performance; Jewish, Christian, or secular; youth or adult.

May it inspire many others to mine the goods of the choral tradition in the parts of worship and life in which those teachings are most needed. And may it be a constant reminder that our musical gifts are the seeds of countless opportunities from which to grow our religious spirit.

Translation by Hartig Hirschfeld, 1905, from Sefaria.org. This excerpt was shortened in the original published version; it is reproduced here with an additional sentence in the quotation.

Mishnat Rabbi Eliezer, Parasha #15

Breishit Rabbah, Parasha #39

I am here indebted to Rabbi Aviva Richman, who taught me these midrashim as part of Hadar’s 2021 Jewish Wisdom Fellowship.

“The Vocation of the Cantor,” in Abraham Joshua Heschel, The Insecurity of Freedom (Farrar, Strauss, & Giroux, 1966).

Thanks for the honorable mention! What a great direction - listening meaningful music to take care of ourselves in horrific times. I'm going to keep that in mind when I publish an expanded article next week on how we can take care of ourselves now, with purpose and joy.

May we see again, soon, the world where the Levi'im spend their days in in the uplifting sounds of spiritual music, as you quoted from R' Yehuda Halevi, bringing everyone closer to God and His ways.