How do you define success?

Is it money? Power? Popularity? Accomplishment?

This is a crucial question. How we answer, whether consciously or unconsciously, will direct the course of our lives.

When we reach life’s end, all of us want to feel like we have succeeded in the things that mattered most: faith, family, and service to others. The rest is unlikely to make the inscriptions on our gravestones, falling instead into what Rabbi Elan Babchuck refers to as “vanity metrics.” These are ways of evaluating your life that make you feel good but don’t tell you anything about your purpose. In the world of our digital selves, whose rise and fall are conditioned by faceless algorithms and dopamine-driven devices, it is easier to become lost in vanity metrics than ever before.

But we don’t have to wait until someone is ordering our headstone to recommit what is truly important. This is the reason rabbis, priests, and ministers continue to give sermons every week. We need constant reminders to recommit to our values over our vanities. Yet what this looks like is not always clear. How do we measure that which is most central and transcendent in life?

Thank you for reading Beyond the Music! If you enjoy reading this newsletter, please consider supporting me with a paid subscription.

Today, I want to invite you to look through a fascinating prism for evaluating the vanity or sanity of our measures — contracts.

I know, most of you were not longing from a visit from HR. But contracts provide insight into the true values of their parties. It is no mistake that the biblical book of Deuteronomy borrows its structure from ancient Near Eastern treaty documents between a lord and vassal. The Hebrew Bible’s focus on covenant thus provides a unique basis for spirituality — rather than aspiring to a life of fame, power, or great deed (as the ancient pagans did), the Jewish way of life is to uphold the Torah, our eternal contract with a loving God.

This probably sounds pretty far afield from the today’s dry world of legalese. Most modern contracts provide largely for legal protections from litigation and acceptable financial terms for services rendered — not transcendent meaning.

Yet there is one type of contract which, at least at times, attempts to strike a happy medium: the clergy contract. For while clergypeople perform measurable tasks, are held to professional and ethical standards, and are subject to annual reviews, they are also in charged with conveying ethics and meaning — something which, like music itself, is so essential yet defies easy metrics altogether.

While contractual goals for clergy may source in meaning and religious literacy, they can just as easily derive from other sources of value. As Rabbi Babchuck recalled from a interfaith conference, there is a crude yet telling question people often ask clergy: “How big is yours?”— that is the size of their congregations. This is the same way we think about CEOs or entertainers — the larger the enterprise, the more “successful” the person is. But we don’t need to look past the even the first phalanx of our own managerial and technocratic classes to see that there is not necessarily a correlation between “success” in large enterprises and virtue.1

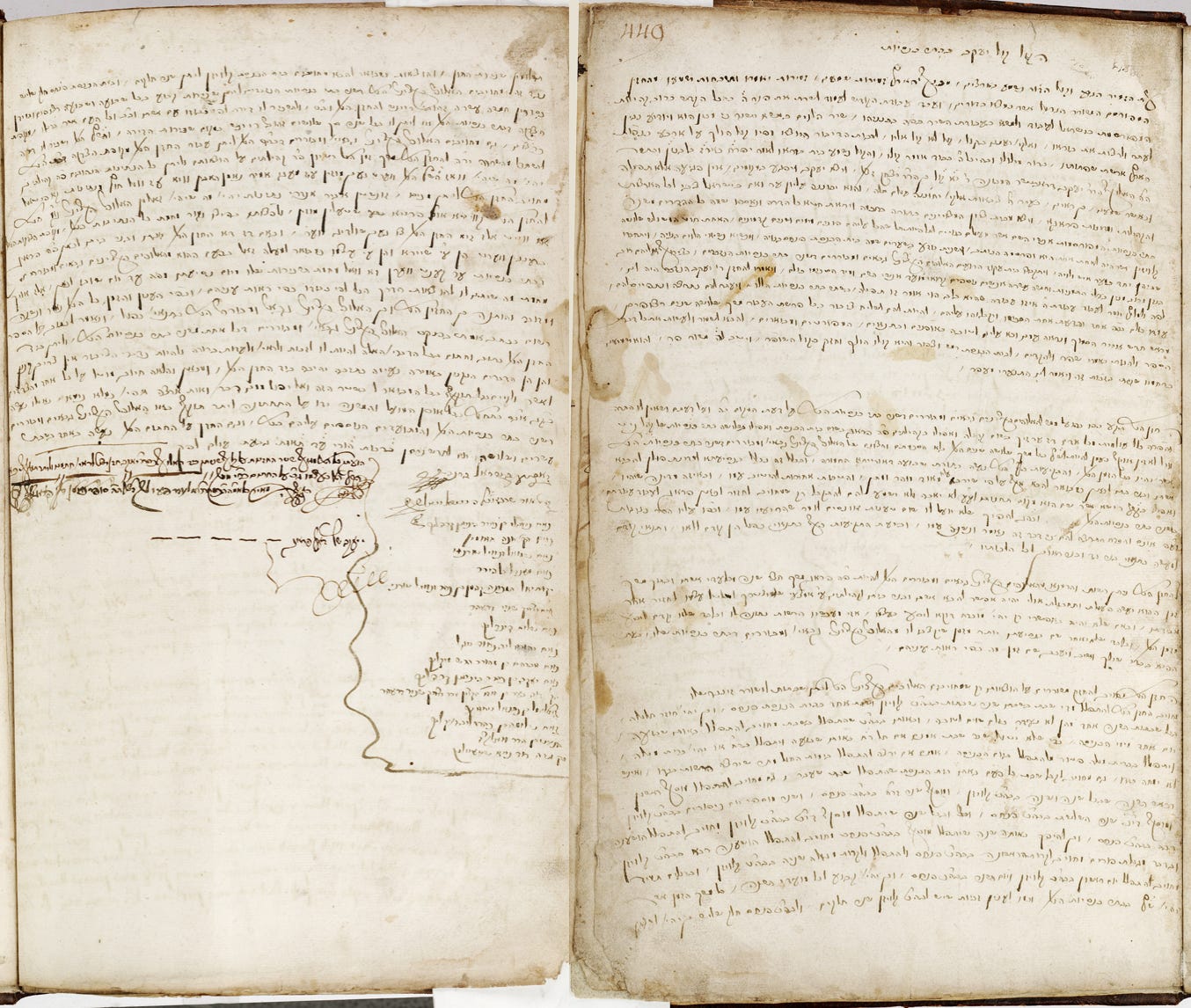

So to give some inspiration towards other ways we might measure success, let me invite you to take a look at my desktop (digital of course), upon which lie two three-hundred-year-old cantorial contracts which are sure to give you the feels.

Both of these fascinating contracts come from the city of Prague, which as we noted earlier this month was the Jewish cultural equivalent of New York City in early modern Europe.2 The first of the two documents describes a deal between a famous Polish cantor who was headhunted to Prague back in 1717 by two prominent shuls — the Klausen synagogue and Pinchas synagogue. The cantor in question, Rabbi Yaakov Drobitscher, was apparently possessed of a fabulous voice, as the contract renders his punny nickname as Rabbi Yoh Kol — “Rabbi What-a-Voice!”

Today we think that rabbis and cantors come from different stock, like the farmers and the cowmen in Oklahoma! But this was not always so. And even with the trends in seventeenth-century Europe which made a non-rabbinic cantorate more and more possible, early modern Prague featured a cavalcade of cantors that were at once scholarly and artistic. Rabbi Drobitscher, headhunted to this Bohemian cantorial metropolis, was one such hazzan.3

His contract is remarkable because it, unlike those in many preceding cantorial generations, represents a full-time job. The compensation, fifteen rhenish gulden per week plus a parsonage allowance and moving expenses, would have allowed Rabbi Drobitscher to discharge his duties without having to wander around town for extra employment. The synagogues even allotted a budget for a synagogue singer (“meshorer zinger”) in order to beautify their services.

The text of the agreement is also rich with biblical and Talmudic allusions, woven with the fabric of the legal and narrative language which defines the Jews eternal contract with God. This captures something which is perhaps lost in our modern day; a contract must fulfill its legal functions and protections, but it does not always capture the religious spirit in which clergy and congregation are united in action. Yet these old contracts spoke in a spiritual tongue.4

The other remarkable thing about the Drobitscher contract is its dual-synagogue nature. We normally think of cantors as fixtures of a particular community, having an indelible and exclusive connection with one specific place. But here, the two communities represent themselves as unanimously enthusiastic to share R. Drobitscher’s talents, though likely in the context of a rotation with their other cantors. The split of duties was two-to-one, with the Klausen synagogue pitching in for two-thirds of the compensation and the Pinchas synagogue for the rest. The division of labor appears almost comical:

“…He shall also be obligated to pray the musaf (additional service) of the first day of Rosh HaShanah of each year in the Klausen synagogue, and the musaf on the second day of Rosh HaShanah in the Pinchas synagogue. And two musafim of Yom Kippur in the Klausen synagogue, and one musaf, in the third year, in the Pinchas synagogue. And each year that he prays Yom Kippur musaf in the Klausen synagogue, he shall be obligated to pray Hoshanah Rabbah in the Pinchas synagogue, and vice-versa, that in the same year that he prayer musaf in the Pinchas synagogue he shall be obligated to pray Hoshannah Rabbah in the Klausen synagogue. And concerning the Megillah of Purim, he shall be obligated to read it first in the Pinchas synagogue and to pray, and to read the Megillah a second time in the Klausen synagogue. And on Festivals he shall always be obligated to pray the first day in the Klausen synagogue and the second day in the Pinchas synagogue….”

This contract is a little further afield from today’s norms, but demonstrates a creative approach to communal funding for a meaning-driven and well-regarded religious professional. Yet it doesn’t hold a Hanukkah candle to may favorite contract from this era — the model cantorial contract of Rabbi David Oppenheim (1664-1736).

This three-century old model contract from the then Chief Rabbi of Prague is filled with flowery expressions of covenant between cantor and congregation. It even employs aramaic excerpts from the traditional Jewish marriage document (ketubah) promising that the community will care for the cantor and “offer provisions for him and his whole household, generously and not modestly, his food and sustenance according to the laws of men, with firewood and a pleasant abode. And he shall be received in a manner which he shall not want for anything.” This is a far cry from the impoverished prayer leaders of Mishna Ta’anit, recognizing that cantors and communities are engaged in mutual care.

In return for this generous provision, the model cantor is required to be early for services, to be learned in his craft to the highest degree, and to read punctiliously from the Torah (with a fine for each error). Moreover the cantor is to “study and teach the children of Israel the order of the prayers which they say from the beginning of the year unto its end, to be one who understands, perceives, listens and hears all of interpretations, intentions, and secret meanings (peirushim, kavannot, v’sodot) of the holy prayers,” including their laws, customs, and liturgical poetry.

Both of these contracts are unique in that they are for specialists —those who are meant to be deeply invested in piety, learning, and deeply meaning what they say and sing. These roles were not just for deeply intentional prayer leaders, but also community educators in those same disciplines of mind, spirit, and music. In short, for engaged carriers and conveyers of covenant.

I do not praise these old contracts to discount our contemporary needs from either contracts or cantors. Yet we should reminded that things can be different. Even the most prosaic administration can be humanized and elevated by the metrics of meaning. We do not only define the terms of our success in “metrics” and “deliverables,” but in the trajectory of lives.

Or as my colleague, Rabbi Josh Rabin, recently penned: “The goal isn’t synagogue membership; the goal is Judaism.”

So too with the Holy One’s contract with us. Our metrics are our mitzvot (commandments), yet they are not simply numbers on a checklist — they exist within a mutual covenant of care.

For the effects of the mismatch between “success” and virtue, with some relevance for today’s polarized environment, see Irving Kristol, “When Virtue Loses All Her Loveliness (1970).”

At over eleven-thousand strong, the Jews were a full quarter of the city's population.

This reminds me of a wise saying of Cantor Sam Rosenbaum, who encouraged rabbis and cantors to share competencies. Writing of such exchange in his own synagogue, he quipped: “I don’t think that the Almighty stamped “hazzan” on my forehead or “rabbi” on Rabbi Gertel’s forehead.”

For the full essay, see “Towards a New Vision of Hazzanut” in Tefillat Shmuel: Selected Writings of Hazzan Samuel Rosenbaum z’’l (1919–1997), ed. Matthew Austerklein (Akron OH: Cantors Assembly, 2017), pp. 33–43.

Modern denominational organizations have attempted to bridge the religious with the administrative for their members. See, for example, the introduction to the Rabbinical Assembly’s guide to clergy-congregation mutual assessment.

the old contracts, and how you write about them, strikes me as romantic.. almost a courtship between cantor and congregation

(or that's just the lens I'm seeing things today after reading comments from the substack post on courtship you had reposted)