It’s time to have the talk.

Yes, the one about Richard Wagner.

Today, I’ll give you my impressions of his infamous antisemitic essay, tell a peculiar story from my bright college days, and reveal how being a cantor helped me understand the inner dynamics of Wagnerian thought.

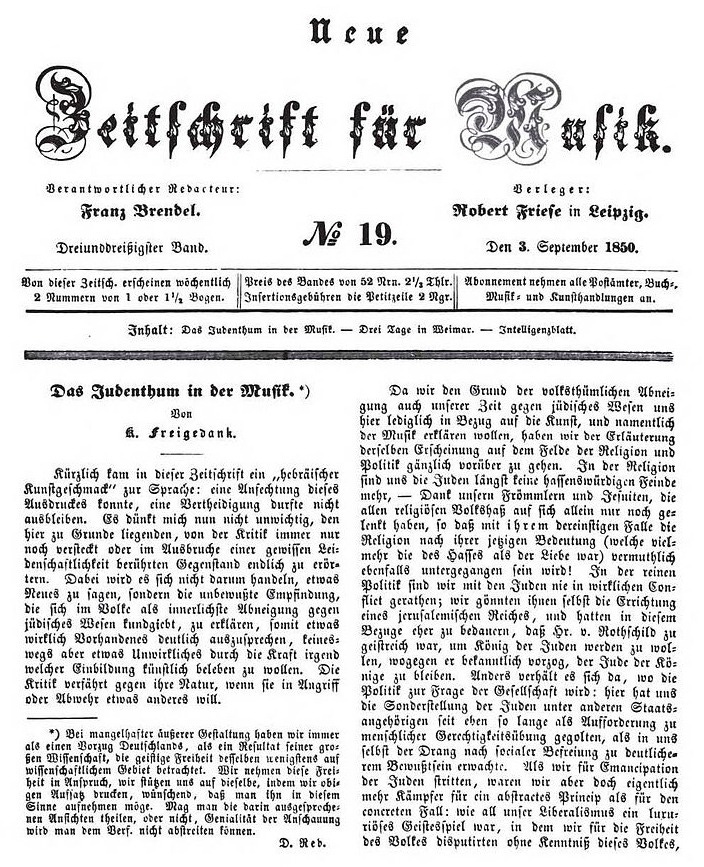

Everyone with an interest in classical music must face the manifold spectres of antisemitism which haunt the halls of its history. Perhaps no dark shadow looms taller than that of Richard Wagner (1818-1883), whose all-encompassing artistry and mythically-rich German operas are still celebrated worldwide. Yet Wagner is known just as widely by virtue of his antisemitism, including his famous essay, “Das Judenthum in der Musik” (“Jewishness in Music”, 1850) which went on to inspire generations of antisemitic artists and leaders—most notably Adolf Hitler.

I will admit that I am an odd person to write on the subject of Wagner. I am neither a devotee nor a scholar of his works, although I have weathered the entirety of Das Rheingold, Siegfried, and Tristan & Isolde from the mile-high standing-room only section of the Vienna Staatsoper.1 While I appreciate his magnificent harmonic palette and heroic scores, I have not, as so many do, fallen deeply in love with his art.

For Jews, falling in love with Wagner can be a dangerous game. For how can you love the one who hates you? Such is the tortured stuff of Romantic novels, yet many Jews won’t give up on the affair. The fêted Anglo-Jewish actor

made a whole documentary on the Wagner question, ultimately taking a “love the sinner, hate the sin” approach — Wagner’s sublime genius and indelible impact on Western music was simply too precious to let go. Disavowing attempts to stain Wagner as perpetual symbol of anti-Judaism, Fry wrote: “You can't allow the perverted views of pseudo-intellectual Nazis to define how the world should look at Wagner. He's bigger than that, and we're not going to give them the credit, the joy of stealing him from us.”Wagner’s antisemitic writings and the Nazi love-affair with the composer have long put a pall over his performance in Jewish circles. The Israeli public and its orchestras maintain an unofficial ban over the playing of his works in Israel. Prominent musicians like conductor Zubin Mehta and Daniel Barenboim have contested this taboo, arguing for a distinction between the man and the beauty and inventiveness of his music.

I cannot even begin to enter into the Israeli debate, which has filled rivers of ink in the Hebrew press.2 But to make my first foray into understanding Wagner, I thought I would go straight to the offending essay itself.

One is struck at first by the title, “Das Judenthum in der Musik,” often rendered as “Judaism in Music.” After reading the full essay, I must say that I prefer to translate Judenthum as “Jewishness”— or as my British colleague David Conway translates it, “Jewry.” For Wagner’s construction of Jewishness, by his own admission, is neither political nor religious — it is on the basis of racial metaphysics.

Claiming his own affiliation with liberalism and the cause of Jewish emancipation, Wagner nevertheless gathers his reading crowd to explore their own subjective feelings of revulsion—not against Jewish citizenship or religious freedom, but against their participation in the German arts. In this the Jews can only be counted as shallow imitators, as they lack an embodied connection to European blood, soil, and language, thereby precluding them from the artistic passions of the genuine “Folk-spirit (Volksgeist).” No aspect of Judaism per se, but the insolubility of the Jewish body within authentic German national self-expression makes the Jew only a parasitic imitator of European music and genuine emotion.

Wagner levels this charge of Jewish impotence in the expression of national passion, and therefore music, at a number of figures, including his more famous and successful contemporaries Felix Mendelssohn and Giacomo Meyerbeer. The former Wagner indicts as a derivative imitator of German greats without original inspiration; the latter as a duplicitous composer of cheap thrills. It is only the “ineptitude of our present musical epoch” which has allowed these Jews, in Wagner’s estimation, to achieve success, for: “only when a body’s inner death is manifest do outside elements win the power of lodgment in it, yet merely to destroy it.”

There are many notable elements of the essay, but the most telling one is how Wagner, then a largely uncelebrated composer, attempted to use antisemitism to change the rules of the musical game. As Ruth HaCohen points out in The Music Libel Against the Jews, the criteria of excellence and success at the box office, as achieved by Mendelssohn and Meyerbeer, was replaced by Wagner with the weight of subjective experience and “authentic” passion — such that the Jew can never feel, his essential substance being eternally foreign to the lands in which he lives. This is an early use of critical theory to transform society from a liberal meritocracy to one in which immutable racial or identity characteristics are the primary source for one’s potential for genius. Although Wagner himself borrowed in his early work from the compositional palette of his onetime Jewish patron, Giacomo Meyerbeer, he nevertheless saw the Jewish success in European music as eternally inauthentic, only an imitation of what a true, blood-and-soil European was born to feel.

This is blood-and-soil nationalism in musical form. And yet in pondering it, I discovered that I recognized an echo of this Wagnerian sensibility from my own experience.

In 2005, a brilliant young linguistics major at my alma mater composed a masterwork for the three combined choirs of the College of William and Mary. The piece, bearing the Hebrew title “Chalom” depicted Joseph’s dream in the New Testament in which God reveals that Joseph’s wife, Mary, will bear the Messiah. Filled with sweeping gestures and cascading sonorities in three languages, from aleatoric angelic choirs to lush chant-like prophecies, the piece was simply exquisite. It soared harmonically, and gushed with the faith and creativity of its author.

During the composition process, the composer consulted with me about the Hebrew, which was to be used in the middle of the piece for a verse from Isaiah. The end result was a Hebrew interlude — for solo voice, followed by a duet — composed in an Ashkenazi cantorial style. Theologically bizarre as it may sound, I auditioned for the solo.

But I didn’t get it.

My tenor friend, possessed of a richer and better-governed voice than me, got the solo, and I entered later to sing the duet.

Despite the fact that this was a thoroughly Christian work, a part of me felt a glimmer of Wagnerian pettiness. This was no fault of my talented friend, nor of the composer. Yet I thought to myself — this is my music! I was the one thinking about becoming a cantor. My friend was only imitating cantorial style. I grew up with it in the synagogue!

It seems so bizarre now to have been even briefly upset over not getting an Ashkenazi-styled cantorial solo in a Christian choral work which placed a Hebrew biblical verse in a messianic context. But at the time, I felt that the composer was using my people’s music, which could only be deeply and authentically interpreted by Jews.

And so in pondering Wagner’s essay, I felt I could grasp his emotional landscape by imagining a parallel scenario: a world in which none of the most celebrated interpreters of cantorial music were Jews.

Let me be clear: I am not saying that only Jews can sing Jewish music, nor that only Jews can sing Jewish music meaningfully. Those who have worked with non-Jewish choirs in synagogues know that these singers are often among the most philosemitic and decent people that you will ever know. I myself am a staunch advocate for the performance of Jewish repertoire in the main of American society, in which it promotes appreciation and mutual understanding. The era of the Johnny Mathis Kol Nidre (above) or Nina Simone’s “Eretz Zavat Chalav” was indeed one in which Jewish repertoire was frequently shared between cultures, envisioning a society which could give honor to diverse arts and communities across our nation.

But the commercial Kol Nidre is different from the Yom Kippur one. Johnny Mathis sang it with soul, but his intention was very different from mine or that of my fellow rabbis, cantors, and laymen. Kol Nidre is a treasured melody and peak liturgical moment that marks the annual lifecycle of the Jewish community, gathering in its fullness on its holiest day to confess its sins. Johnny Mathis surely felt emotion and poured it out from a deep place. But in a word, it was not his mitzvah. It did not emerge from the world of inner religious life, sacred texts, communal obligation, and intention (kavannah) that it does for the Jew.

I’m not bothered by Johnny’s rendition, and there are parts of it that I love. But if I lived in the world where all of the greatest cantors and masters of the traditional cantorial style were not Jews at all, I might have an inkling of Wagner’s sentiments about European music. For Wagner, German peoplehood provided the ultimate source of feeling and musical authenticity, just as Jewish peoplehood and faith gave the cantor his authentic passion for prayer.

Ironically, Wagner’s approach to the folk spirit of national music was first embraced by an unlikely source — Jewish musicologists. As James Loeffler pointed out in a brilliant article, scholar-composers like Abraham Tzvi Idelsohn (1882-1938) and Lazare Saminksy (1882-1959) independently came to a positive evaluation of Wagner’s writings on Jewish music. The famous essay had, in fact, posited that Jews were once possessed of a national music when they were in the Hebrew cultural milieu of their biblical homeland; the only possible source of authentic “folk-spirit” that the modern Jew could draw upon were his own liturgical melodies which linked him this ancient era.3 Lazare Saminksy, one of the core composers and lecturers of the St. Petersburg School, similarly celebrated the rebirth of Jewish national music through embracing “the rich seams of our ancient Jewish melodies” as the “true foundations of Jewish music.” He even claimed, like Wagner, that “Jewishness” could even be evinced within the great compositions of baptized composers like Mendelssohn, lauding: “Such is the strength and stubborn tenacity of the national spirit.”

Idelsohn took this one step further. Taking up the Wagnerian challenge, he sought throughout his life as a cantor and musicologist to trace the lineage of Jewish music back to its “oriental” and “pure” ancestral roots in biblical Israel. For Idelsohn, Wagnerian premises further reinforced his own Zionist vision in which the Jew with his own national homeland and language could truly revive Jewish national art. Thus writing on the subject of Wagner in 1908, Idelsohn boldly proclaimed:

They say that he was a hater of Israel, and I say the opposite. For he did us a great favor since it was he who first suggested that Jewish music exists. Therefore this “hater” is dearer to me than thousands upon thousands of “lovers” of our people.

Modern musicology has largely debunked such metaphysics: A “folk-spirit” is no more physically inheritable for Germans than it is for Jews. Wagner’s intensive focus on subjective feeling and European ancestry were but a subversion of the standard criteria of artistic excellence — beauty and popular appeal. His rivals, Mendelssohn and Meyerbeer had achieved this in spades. Thus Wagner penned “Jewishness in Music” to recast artistic success and authenticity in immutable racial and identitarian terms, seeking to stack the deck, card by card, in his favor.

Judging art on an identitarian basis tells you that you are looking at a religious system at work. For the Jewish religion, obligation and sincerity in prayer largely trumps aesthetics — Johnny Mathis can do a great Kol Nidre, but an amateur cantor praying with kavannah is of more value. Through the prism of the cantorial experience, we can see that Wagner was part of an evolving religious worldview of human body and its passions— an ultimately godless faith of cultural supremacy which found welcome ears among European ethnonationalists. Whether to compensate for his insecurities as a then-second-rate composer, or to use antisemitism to get ahead in the world, Wagner created one of the sacred texts of a closed, racial cult into which only blood could confer membership. This outlook was and remains diametrically opposed to the democratic societies into which Jews contributed their own blood, sweat, tears, and music, and in which millions of us still find our homes.

The contrast with Jewish music here is instructive. The original Wagnerian cult of art was a closed one, deterministic and based on immutable ethnic traits. While Judaism is an ethnicity, unlike Wagnerian racism, conversion is possible, and diverse ancestry no obstacle to achieving the authentic feeling. Moreover, sacredness in Jewish music is not conferred by blood or family, but by use for sacred purposes.

This is why, contra Idelsohn’s attempts to divide it into authentic and inauthentic, Jewish music is as naturally multiplicitious as the many nations of the world in which Jews have dwelled. Cantorial music is sacred not because my purebred Jewish ancestors did it, but because it expresses my spirit, my faith, my people’s liturgy, and my religious commitment. The Jewish body, obligated in Torah and mitzvot, is the vessel, but it is what lies within —one’s intentions — which count most of all.

Wagner wrote amazing music, and it can and should be enjoyed. But it should also serve as a warning against identitarianism in music.

You never know who it may be inspiring in the future.

A word to the wise: Don’t bring your vocal score to a Wagner opera in Vienna. The page-turning may disturb your neighbors, as I was once quite rudely made aware of at the interval.

My thanks to Alon Schab and Sam Berlad, two people who know way more about Wagner than I do, who read drafts and offered helpful comments to this article.

For Hebrew-language volumes on Wagner, Jews, and Israel, see Rina Litwin, Who is Afraid of Richard Wagner? (Hebrew), 1984; Ami Maayani, Richard Wagner (3 volumes, Hebrew), 1995; Na’ama Sheffi, The Ring of Myths: The Israelis, Wagner and the Nazis, 2013; Irad Atir, An Antisemitic Opera? New Perspectives on the Art of Richard Wagner (Hebrew), 2023; . My thanks to Alon Schab for referring me to these sources.

Wagner’s father-in-law, Franz Liszt, wrote similarly in his 1859 book on Hungarian music. The difference is that Liszt, unlike Wagner, had many positive encounters with one man who embodied the realization of this “reclaimed” Jewish liturgical music as national art: Cantor Solomon Sulzer. Read more here.

![[Archive] The William and Mary Hymn [Archive] The William and Mary Hymn](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!6PXL!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F68202003-1c23-414d-afe2-66eaee8b8c77_1280x720.jpeg)

So interesting thank you! Almost cultural appropriation, but with bloodlines. I think it redeemed Wagner a bit. for me anyway.

Thank you for the video. You chose one of the more beautiful Wagner arias, with one of the more beautiful tenors so it places his work among the greats. Good for you! I listen to cantorial music every day. There is a beauty in it; the רגש that comes from it and hits you someplace deep in your ancient soul. Most cantors could sing Wagner but why?