I am a scholar and I know my field — the green and pleasant land of Jewish musicology. But when I reach the edge of my sceptered isle of knowledge, the majestic white cliffs of wonder tempt me to step off, free falling into chasms of curiosity.

There is delight in plummeting into this channel of inquiry, yet the horizon of understanding often seems eternally out of reach. There are no cartographers in this sea of Socratic knowledge — only the experience of becoming a better sailor.

But perhaps this is a good thing. Despite AI’s ever waxing capabilities, we don’t need a great theory of everything to find its meaning. Like the old Jewish adage goes, a good question is better than a good answer.

Thank you for reading Beyond the Music! If you enjoy reading this newsletter, please consider supporting me with a paid subscription.

I sat down recently with a senior colleague who had read a piece of my research. I was proud of my work. I had charted new academic waters, exploring many sources on Jewish music which had never before been discovered or analyzed in depth. All of this she praised. But, she gently chided me, I had not respected the sources themselves enough. I had used them in my argument, forcing their resonances into beautiful harmony. But I had not seen them as an Other — uniques voices not meant to fit into a thesis, but to speak for themselves.

”The concern for the other breaches concern for self. This is what I call holiness.”

-Emmanuel Levinas

The desire for oneness, for a unifying theory of everything, has driven writers in every discipline known to man. Religious thinking is often no different, seeking the oneness of existence in the presence and will of its Creator. But is this a Jewish idea? Is divinity simply the great thesis for the unity of everything?

This question hit me hard over the head this weekend, as I sat in the beautiful Sibley Library at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester. Treated to silence and the helpful attentions of librarians, I found myself on a search for a seventeenth-century music treatise from which my early modern cantorial subjects might have learned. There, I came cross Athanasias Kircher’s Musurgia Universalis — “The Universal Musical Art (1650).” For Kircher, like so many Christian theorists, harmony in music was a reflection of greater harmonies in the spheres and the heavens above — a grand theory in which musical beauty was just one emanation of philosophical and theological perfection.

This sense of harmony—the beauty of transcendent perfection — is what is so moving about classical music. Though it can build skyscrapers of contrasting textures, sonorities, and emotions, it is rooted in the old, Western principles of harmony and voice. In tonality, melody, harmony, and the will of the Composer, all is One.

Yet there is something imperial about such oneness. For the world’s empires, “harmony” was often a term conquest or submission. The Egyptians saw their Pharaohs as gods who held the natural world together in harmony. The pax romana — the Peace of Rome (27 BCE - 180 CE) was also a time of aggressive military expansion. Those who were “disharmonious" in both worlds were suppressed or silenced.

My colleague, Judit Niran Frigyesi, wrote of coming to this realization while studying Gregorian chant:

“I had been drawn to classical music because it dared to speak. It was able to tell, in flames of passion, the story beyond the words. The joy of speaking was now being turned against itself. The whole enterprise began to resemble a chase of wild animals panting from exertion as they were running up the slope toward the peak of greatness. Where previously I had heard impassioned speech, I now felt the brutality of the rhetoric. These symphonies, sonatas and nocturnes —they all wanted to “elicit an aesthetic response,” to lure me into feeling. There was an imperative in every gesture: be sad or rejoice, but whichever it is, listen to me for it is the great ‘I’ that speaks.”1

The imperial nature of classical music, especially its more complex forms, has not only been noted by academics. Just ask the mall executives and convenience store owners who have long used it to deter crime and vagrancy. While classical music can elicit palaces of thought and textures of feeling, the genre also perhaps speaks more than it listens. Its harmonic imperium only asks its subjects to hear, not to respond.

Kircher’s treatise on universal art remained open before me on the library’s slick wooden table. I flipped through the pages in search of how Renaissance Jews would have learned to read Western music. What I did not expect was that Kircher had his own interest in me.

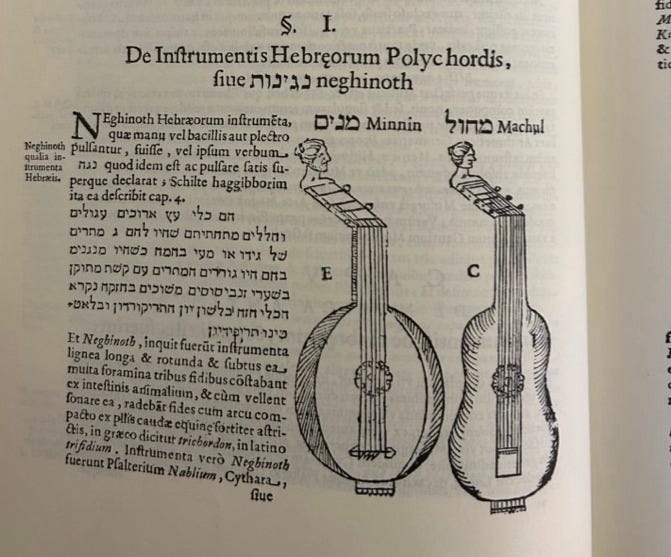

As part of his analysis of ancient music, Athanasias Kircher attempted to document the musical instruments of the Hebrew Bible. To get an insider’s perspective, he quoted heavily from the Hebrew-language volume Shiltei HaGibborim (1612) by Abraham Portaleone, an Italian-Jewish physician who wrote describing the arts and sciences of the Jerusalem Temple, including its musical instruments. Kircher’s extensive use of Portaleone provided the biblical foundations for his sense of music, presented side-by-side analysis of Greek music and the classical modes. Jerusalem and Athens, the two cultural poles of the West, were thereby brought together in Kircher’s detailed and comprehensive construction of a unified philosophy for “universal” harmony.

Grand theories create immense beauty—but do they leave space for wonder? In searching for universal harmony, do we miss the beauty of the immutable, unassimilable otherness of that which is considered noise? The history of classical music, however noble, is also the soundtrack of those who persecuted those greatest of noisemakers — the Jews. Whether from the “music libel” of Christian anti-Judaism or from blood-and-soil musical nationalism, Jewish music-making was long pilloried in the West as ugly, disorderly, and derivative.

These critics weren’t wrong. Jewish music can have a beautiful ugliness — the sound of a mamlechet kohanim, a kingdom of priests, in which every person is therefore individually obligated to speak liturgical words out loud for themselves, regardless of their vocal beauty. This creates the thrumming, shamanistic, disorderly world of davening. Its religious cacophony, a vibrant world of parallel prayers coming in and out of existence, is an expression of that encounter with the Other.

In this sacred soundscape, the worshiper and the Lord are not One. They are eternally and belovedly two, the permanent eros of the distance between them creating eternal yearning and dveykut (“cleaving”) from one Other to another.

Even Kircher himself proves the somewhat risible nature of the idea of universal harmony. And he does it through the most bizarre and unexpected of images — the “American sloth.”

No, not that American sloth. I mean the seventeenth-century American sloth.

That’s better.

I don’t think Kircher ever visited America. If he had visited, he might have found out that sloths went extinct here eleven-thousand years ago (except for those beer-drinking ones from the Super Bowl). But somehow he did uncover a scientific anecdote about a species of sloth who naturally sang the six pitches of hexachordal music theory. Since the beautiful in music must follow the laws of nature, Kircher taught his readers only to modulate to the keys of these six pitches, reflecting the natural tonality of the American sloth.

If you want to hear Elam Rotem and Sean Curtice explain this particularly weird moment in music theory, watch here (start at 28:55):

Maybe the unity of the music in the universe makes as much sense as this mythical sloth. As I noted when I began this writing journey, Judaism has no word for such musical harmony. We had to borrow the term— harmonia — from the Greeks. The closest thing we have is the word for interpersonal harmony, and that word is very well known. The word is shalom.

Yet that does not keep people, in classical music or any other genre, from searching for shalom in the embrace of music—present company included.

Looking at the question of the Jewish potentialities of classical music, I wonder if I am perhaps engaging in a sort of magical thinking, imputing Oneness where Otherness should come first. For the respect of both Judaism and classical music, perhaps the dignity of our differences is the most important place to start.

Standing in my field, I look off into the waters of the unknown. I have my questions as my compass, but no map of the unending seas. Yet it is enough to be but just and true to my own imagination, in those worlds of eternity in which we shall live forever.

Therefore I will not cease from mental fight, nor shall my pen sleep in my hand.

Judit Niran Frigyesi, Writing on Water: The Sounds of Jewish Prayer (New York: CEU Press, 2018): 92.

Good stuff

My high school [Northfield Mount Hermon, founded by Dwight Lyman Moody] alma mater is "Jerusalem", and hearing and singing it really transports me. There I also learned the Priestly Blessing as the "Northfield Benediction". I'd love to send you a copy of the music since I can't attach it here.