All over the world, cantors are breathing a sigh of relief. They’ve just completed two days of intense Rosh Hashanah worship in their communities, and they can take a deserved rest after a job well done.

But today is also a fast day. Tzom Gedaliah (“the fast of Gedaliah”) commemorates the end of Jewish autonomy after the destruction of the First Temple. It is also the third of ten days of repentance, culminating in Yom Kippur. So even as prayer leaders rest, today is also a fitting day for our self-reflection.

Last week, we considered the exulted task of both Queen and cantor in representing their people with inclusivity and compassion, grounded in the high ideals of their office. But royals and cantors are just as well known for their transgressions as they are for their duties. This shared duality of embodying both the sinner and the saint is part of what I believe to be a subconscious social function of both offices.

And once again, it is illuminated by Netflix’s The Crown.

In Season 3, Episode 2 of The Crown (entitled “Margaretology”), the character of Prince Phillip recounts a theory of the House of Windsor, proposed by the Queen’s private secretary, Tommy Lascelles:

“There have always been the dazzling Windsors and the dull ones. Your father..a saint, but dull. Sorry. Your grandfather too. George V? Deadly dull. At the height of the Great War, when the Tsar and the Kaiser and the Emperor of Austria were dazzling the world, where was he? He was sticking stamps in his album….

…but alongside that dull, dutiful, reliable, heroic strain runs another. The dazzling, the brilliant, the individualistic, and...the dangerous. And so, for every Victoria, you get an Edward VII. For every George V, you get a Prince Eddy. For every George VI, you get an Edward VIII. For every Lilibet, you get a Margaret.”

Like the Lascelles theory of the Windsors, two similar strains of cantor echo throughout the ages — the dull and the dazzling. The “dull” strain of cantors often embraced the limits of communal and religious life, railing against the excesses of those that profaned their profession. The “dazzling” strain impressed the world with their artistic abilities and often transformed the Jewish musical landscape through their embrace of new styles and technologies. Yet they sometimes cast off many limits, ritual and even ethical, that come with the traditional office of the cantor.

This cantorial dance between the dull and the dazzling repeats itself generation after generation:

At the turn of the 18th century, cantors like Yehuda Leib Zelichower and Rabbi Shlomo Lifschitz railed against the impieties of their musically unbridled fellow cantors and advocated a return to religious normativity, even amidst the changing nature of music and the diverse backgrounds of prayer leaders in their midst. Their dazzling contemporary, Cantor Yokel of Rzezow, was famous throughout Europe and traveled across the Continent through Poland, Bohemia, and France. Yet his contemporaries would also censure him for his laxity with the liturgy, and for this fault even blamed him for the tragic collapse of the women’s gallery at his synagogue in Metz.1

Salomon Sulzer (1804-1890), the father of the modern cantorate, was a dazzling cantor, but didn’t trust the unwashed cantorial masses to follow in his artistic footsteps. After a lifetime of synagogue innovation, secret art song singing, public musical work, and community leadership in Vienna, Sulzer’s advice to cantor was to embrace the dull and the dutiful and to eschew artistry:

“Of primary and most pressing concern is the recruitment of new talent into the cantorate and the maintenance and cultivation of liturgical music. These two objectives need to be distinguished: we cannot risk having a conflict within a single individual between the artist and the holder of the clerical position. Moreover, it often happens that [musical] talents work to the detriment of the controlled and dignified bearing of the ministering functionary. In the interest of the priestly office and of art, it would be beneficial to emancipate the musical aspect from the function of the cantor, and the cantor should be kept free from the idealized passions of the artist-performer.”2

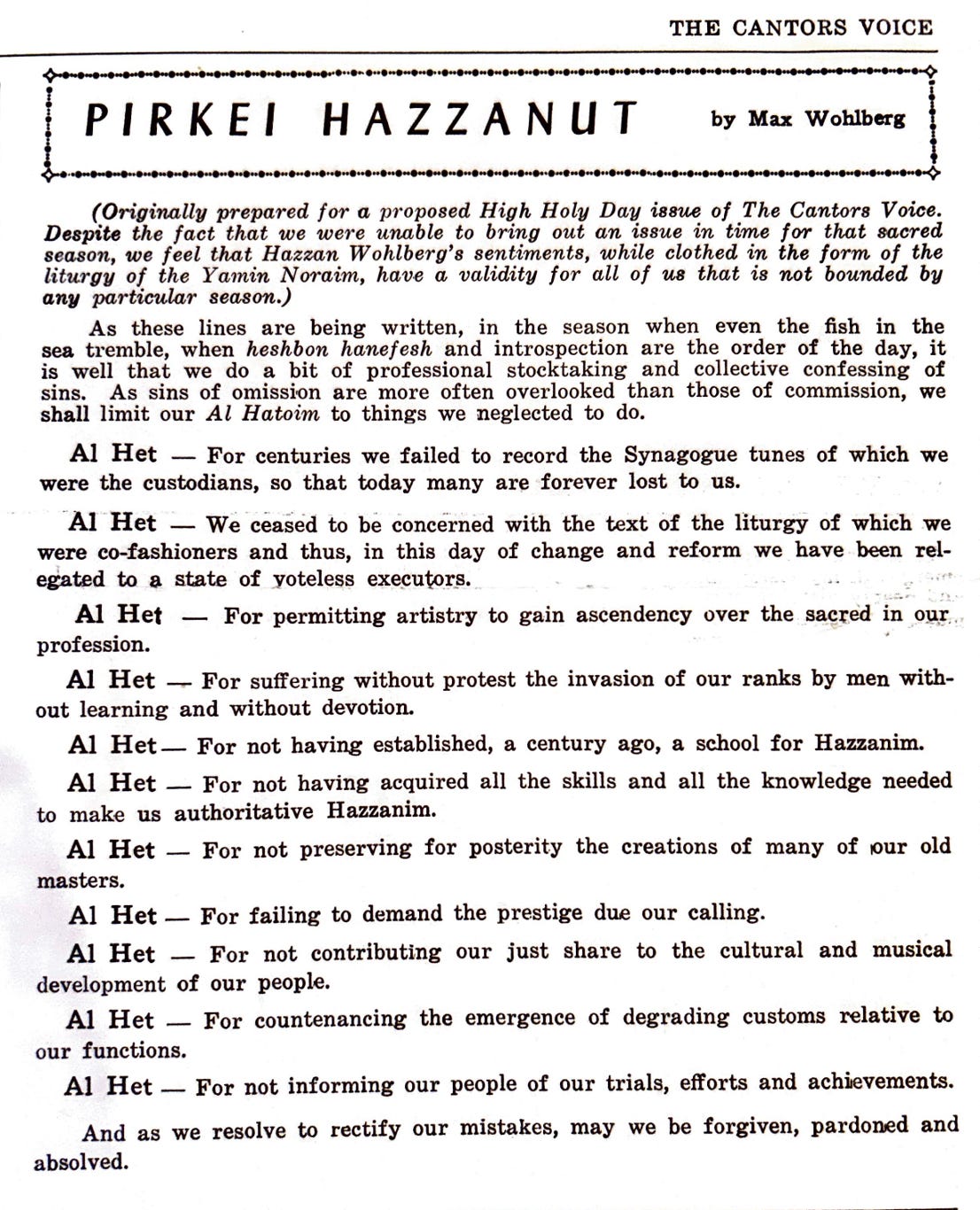

The Golden Age of Hazzanut at the turn of the 20th century continued with similar debates. As Jeremiah Lockwood expertly lays out in his recent article “What is the Cantorial Golden Age?,” cantors like Yossele Rosenblatt and Gershon Sirota rose to prominence through rise of the gramophone industry and the mass marketing of cantorial sound, while conservatives like Elias Zaludkowsky & Pinkas Minkovsky painted these innovations as profanations of a sacred art form. “Hefker” [wanton] chazonus, they would call it, and looked down on its enmeshment with commercialism, show business, and religious laxity. For while virtuosic cantorial sound ascendantly laid claim to prominent territory in Western culture, its greatest artists were not always known for their greatest adherence to Jewish law and custom. In many ways, the professional organizations of the cantorate like the American Conference of Cantors and the Cantors Assembly were meant to make this wild musical profession “respectable” and domesticated for the suburban synagogue community.

I once edited a short book on the writings of the Cantors Assembly’s forty-year Executive-Vice President, Cantor Samuel Rosenbaum. Sam was dazzling in his own way — an administrator, author, pastor, lyricist, orator, Emmy-winner, teacher, and cantor. But he saw himself as a counterpoint to the excesses that his organization sought to combat. In his twenty-fifth annual address to the Cantors Assembly in 1972, Sam reflected on the ongoing distinction between cantorial art and popular art.

There is a very fine line which must be drawn between hazzanut and art, between hazzanut and all other kinds of music, between the hazzan and any other kind of artist. The temptations are great to substitute the theatrical for the dramatic, the popular for the authentic, and the glamorous for the quietly routine.

In our early days the Assembly faced that challenge and I am pleased to say, we overcame it. But we are in another generation and I see the same old temptations lurking about us. I wish it were possible to lay down some rule by which one could save himself from succumbing to them, but there isn't, and there is no guarantee that anyone would observe it if it were laid down.3

I spend a lot of time with cantors. If I can say it, we are a fun bunch. In some ways, the cantorial community’s acceptance of a broader range of religious practice is typical of musicians, who are united by shared aesthetics before shared ethics. This musical inclusivity is also like that which the Sovereign or the sheliach tzibbur4 require to compassionately represent a diverse people or nation. I have met many pious and wonderful cantors who are both loved by their communities AND are dazzling in their own right. But as a historian, I think that the Lascelles theory of the cantorate stands. The question is — why?

’s masterful book, Music: A Subversive History, holds a potential key to the answer.5 In his chapter entitled “Subversives in Wigs,” Gioia describes the key transformations in the role of the artist brought about in the West by the end of the 18th century:“First, music becomes inextricably tied up with biography and character, to such an extent that pure musicology, any definition of song or style by the notes alone, turns into a fool’s gambit, a willful refusal to read the personal memoirs inscribed in the staff lines….even symphony and tone poem, or, in an extreme example, liturgical music that ostensibly aims to celebrate the Creator with a capital C, end up manifesting the composer-creator with a small c.

The second tendency, linked to the first, finds audiences demanding not just autobiography from their leading composers, but radical, explosive self-representations that proclaim the composer’s greatness and exemption from all the everyday rules of ordinary people. And then there’s the unspoken third factor that lingers hidden in the listener’s fantasy life: namely, the implication that they are enjoying this same freedom by extension, a kind of surrogacy of outrage. As fans, they, too, can enjoy the snubbing of authorities and the breaking of rules.”6

This idea of the celebrity artist as a vehicle for surrogate freedom from limits, to my mind, is also simmering the background of the aforementioned Jewish worship wars between the dazzling and the dull. The dazzling side of any religious art always includes the danger of celebrating the powers of the earthly creator, rather than the Heavenly One. But for many audiences, that is just what they have wanted. This pole of the cantorate celebrates musical power and can proclaim God’s greatness with great volume, but its sitra achra (its dark side) is the vicarious celebration of the power and freedom of the human being, even from the strictures of her culture or faith.

Such a story is all too familiar with many public figures today. We exalt them for their abilities and influence, not their duty. We laud them for the limits they have rejected, not the limits they have embraced. This is not just a problem for the cantors or the Windsors.

Sure, I sound like an old curmudgeon. And I think that Judaism is in desperate need of a real theology of the professional musician. But Yom Kippur is coming, and like the gentle beating of our chests as we confess our sins, the echo of the truth knocks upon our hearts.

This year, let all who make music embrace their royal vocation, bringing together both aesthetics and ethics, beauty and piety. May our confession and prayer, offered earnestly, be a fitting crown for the Sovereign of all.

This event was commented upon by both R. Shlomo Lifschitz (who succeeded Yokele in Metz) and the businesswoman and autobiographer Glikl of Hameln, who was present at the tragic scene. See The Memoirs of Gluckel of Hameln, trans. Marvin Lowenthal (New York, NY: Schocken Books, 1960): 271; R. Shlomo Lipschitz, Teudat Shlomo, 15b.

Salomon Sulzer, Denkschrift an die hochgeehrte Wiener israelitische Cultus-Gemeinde (Testament to the honorable Viennese Jewish community) (Vienna: 1876). Trans. Caroline Sawyer. Ms. Sawyer summarizes: “Sulzer wrote this "testament" for the community on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of his office and of the City Synagogue itself. He regarded this essay as his final utterance regarding his hopes and advice for the development of synagogue worship.”

Tefillat Shmuel, Selected Writings of Hazzan Samuel Rosenbaum z’’l (Akron: Cantors Assembly, 2017): 22. The full book is available for free on my Academia.edu page.

Heb. for prayer leader, literally “representative of the community.”

I am grateful to Cantor David Lipp for introducing me to Ted Gioia’s work. Ted’s writing has been to my own much like what John Dewey’s was to Mordechai Kaplan.

Ted Gioia, Music: A Subversive History, 255-256.