“We are the channel, we are not the flow.”

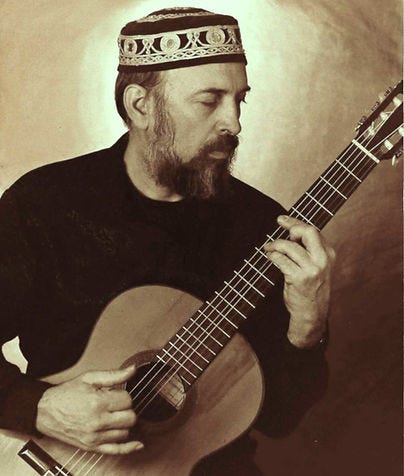

—Hazzan Jack Kessler z”l (1944-2024)

Last Thursday, my teacher Hazzan Jack Kessler passed away.

Today, I face the hole that he left in the world. I miss his knowing smile, his belief in his students, and his love of tradition.

And I am also faced with a great mystery. As the Talmud writes:

“When Rabbi Meir died, the composers of fables ceased. When Ben Azzai died, diligent students disappeared…When Rabbi Joshua died, goodness ceased from the world…When Rabbi Akiba died, the glory of the Torah ceased…”1

With Jack’s passing, it is hard to measure the degree of what has ceased in this world.

When I graduated from cantorial school, I was already interested in more advanced learning. Hot on the tail of a Doctor of Ministry degree, I found my way to ALEPH: Alliance for Jewish Renewal, which required its doctoral students (and all of its future clergy) to become a part of the Davennen Leadership Training Program (DLTI). Whether I was going to do the whole program or not, I thought I would give this two-year series of twice-annual retreats a try.

I knew a little of this world from my time living in New York, where I attended and wrote an ethnography of Romemu, a then-startup renewal congregation under the charismatic leadership of Rabbi David Ingber. But at Isabella Freedman Retreat Center in the far-flung farms and forests of Western Connecticut, I found myself deep in the world of neo-chasidic, new age, and experimental Jewish prayer. Surrounded by Jewish priestesses, yogis, and spiritual seekers, DLTI was at once a thorny obstacle course for my theological rationalism and intellectualism, and also a warm, musical, and open-hearted gathering of people who sincerely wanted to talk to God and feel His presence.

In the devilry and delight of these retreats, I made lifelong friends. I met my wife. And I discovered Jack.

Thank you for reading Beyond the Music! If you enjoy reading this newsletter, please consider supporting me with a paid subscription.

Jack was an enigma. In a sea of alternative spirituality, this was the guy teaching traditional Lithuanian nusach, improvisation, and even the occasional bit of Koussevitsky. His classical vocalism and cantorial aesthetic might have seemed out-of-sync with the wild, mystical sprites who inhabited the Connecticut woods. Yet his collaborative spirit, disarmingly jocular personality, and immense musical talent seamlessly weaved this old world aesthetic into a new age fabric.

This was no easy task, but Jack was not your average cantor. The child of European immigrants, Jack was the French-speaking son of a Hungarian rabbi who carried the old world in his bones. During his twenty-year career in the Conservative pulpit, he also studied composition with Arthur Berger and Harold Shapero at Brandeis, and voice with new music specialist Bethany Beardslee at Harvard. He was steeped in the Western tradition, singing his fair share of opera, oratorio, and new music.

Yet from the heights of his cultured formalism as an Ashkenazi hazzan and Western composer (which included some twelve-tone hazzanut), Jack was also the irreducibly impish, groovy child of the Joan Baez folk era, the swinging sixties, and the world-altering influence of Reb Zalman Shachter-Shalomi z’’l. This was a nigun-filled cantor who played backup for Shlomo Carlebach, and who transformed himself into an improvisational, cross-genre artist in klezmer, kirtan, and Middle Eastern music.

All of these sides of Jack came together in his vision for the ALEPH Cantorial School, where he was the director since its founding. Speaking of the role of the cantor, he waxed rhapsodic yet religious:

“The Hazzan is much more than a performer of music. We see ourselves as artists, healers, and teachers. Our mission is to be modern-day “kohanim” – opening a channel and creating a container for profound heart-expanding interface with higher consciousness. We do this in the spiritual wilderness of the contemporary era. Jewish life has suffered greatly in the last century, and renewal/rebirth is the challenge. Our tools are the liturgy, the musical tradition, our voices, our imaginations, and our souls.”

Jack, a kohen himself, understood that the cantorial tradition was the domesticated form of Jewish shamanism. And his ability to unfreeze and re-animate nusach for generations of disconnected Jews and future clergy had a singular and enduring impact on the soundscape of the Jewish Renewal movement.

In a world of depth-plunging chest singing, Jack made space for sacred sonorities reaching beyond earth-mother musical mimesis. Not only could godliness be found in the rhythmic chant and the beat of the drum, but in the soaring soprano or the florid fioratura. With Jack, the sound of the cosmos was an infinitely more inclusive and grander place.

Hazzan Jack’s impact was not only because of his immense talent and knowledge — it was because he was with the people.

It is difficult, in any tradition, to translate the old world to the new. In the world of Jewish Renewal, Jack encountered all sorts of people, many with difficult Jewish backgrounds, or who might have had an allergy to hazzanut from either personal preference or past experience. But Jack — the groovy guy, the jokester, and even the pirate — knew how to be on a level with each person.

Jack’s innovations in the realm of nusach reflected this desire to bring down the shefa of musical flow bashamayim uva’aretz — across the vocal range. He wrote nusach for the whole year, including special pieces and choral works for his students and colleagues. He created his own liturgical version of kirtan (he called it korban), creating responsive phrases in traditional nusach that could carry a congregation in traditional chant. And of recent note, he developed a system for chanting the Hebrew scriptures in English with traditional Ashkenazi cantillation (“trope”). He became particularly known for this in recent years, as synagogues across the country utilized his cantillated settings of modern American prophetic texts like The Declaration of Independence and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s “I Have a Dream” Speech.

Jack was a true musical levite — from the Hebrew root for “to join” or “to accompany.” This was also clear from his incredible devotion to his wife and partner, Rabbi Marcia Prager. As he led prayer with her, effortlessly accompanying with jazz chords and sensitive harp-like cascades on his classical guitar, he practiced partnership with flexibility, humility, and a servant heart. He accompanied her devotedly for many decades of marriage, and recently as a caretaker in her bouts with illness. Now that he has been laid to rest, his accompaniment, both spiritual and musical, continues from the spheres above.

I will never forget studying Jack’s compositions for the first time. I was immediately impressed by the sophistication and depth of his old-new compositional voice, and I still use a number of them to this day. These compositions resonated throughout the Orchard of Torah — from the peshat of the notes down to the musical sod —the deep secrets that came down to us through the fullness of Jack’s incarnate and reincarnate cantorial spirit.

But what I most remember about Jack is his timeless teaching about voice: “We are the channel, we are not the flow.” While a perfect description of vocal technique, I also think it is a perfect description of the man himself. Meeting him for the first time, one might not assume that this jaunty, joke-cracking hippie would be one of the great cantorial teachers of America.

But that is the point. Jack was only a channel; the flow of musical inspiration that he drew down was truly from another world.

I do not think I will ever myself fully grasp what has departed the world with Jack’s passing. That mystery now forever occupies a home in the hearts his beloved family, students, and the movement he helped to found. All of us who knew him have been blessed to have gathered so many of his nekudot tovot — his good points. As Rebbe Nachman taught, bringing these good points together is the root of composing a melody.

The days go by, the year passes. But the melody always remains.

Jack, time has passed. But you have released into the universe, in us, a shining galaxy of good points. From here on out, we are your melody.

Rest in the Bonds of Life, friend and teacher.

Beautiful tribute, Matt. I'm so sorry for your loss. For our loss. And grateful for all we've gained through Jack's light. I'm glad you are carrying his Torah.

Really, really beautifully put, Matt. You've captured something very spot-on about his essence. I'm also finding it hard to fully comprehend what we've lost.